Plays and Playwrights

Essay

Upon first glance, it may seem odd that in Philadelphia, the intellectual heartland of the American Enlightenment, the first drama did not play until April 1754, over seventy years after the city’s founding. That play, The Fair Penitent by Nicholas Rowe (1674-1718), was licensed for twenty-four performances, with the warning that the license would be revoked if anything in the production was deemed indecent or immoral. But the show proved so popular that, rather than revoke its permissions, Governor James Hamilton (c.1710-83) extended its run for an additional six performances. The Fair Penitent ran for ten weeks and sparked a desire for the theater in the city that long continued. The local theater scene inspired homegrown talent and served as a setting for local writers and others from farther afield who have drawn on the city’s historical centrality—realistically or allegorically—to craft compelling American drama.

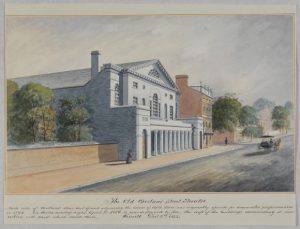

In the early years of Philadelphia theater, transatlantic influences featured prominently. In the tradition of Shakespeare and Nicholas Rowe, Thomas Godfrey (1736-63) borrowed freely from older classical works to write The Prince of Parthia (published 1765). This romantic tragedy in blank verse played at the Southwark Theatre in 1767 and marked the first time an American-authored play was staged by a professional company. Like the popular British Renaissance and Restoration revivals that dominated the American stage throughout the eighteenth century, Parthia centers on a romantic complication among the upper classes, with a bit of heroics thrown in for good measure.

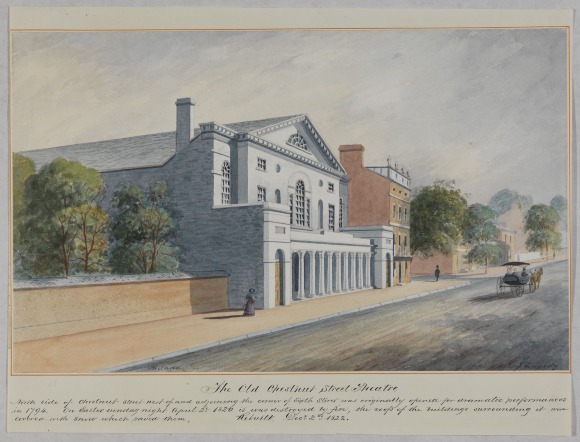

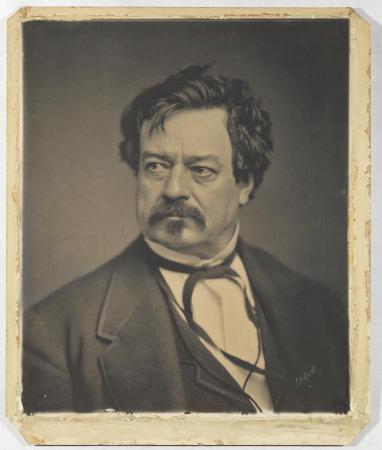

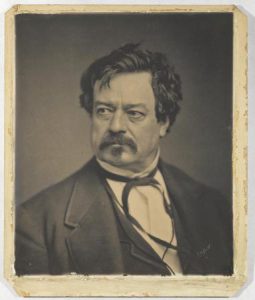

The first generation of Philadelphia dramatists took a page from Godfrey, but they also were intent on incorporating the city’s history into their works, often at the Chestnut Street Theatre. Among those who established their careers there, Susanna Rowson (1762-1824) came to the city from London to be part of the Chestnut’s first company of players and playwrights. She wrote the comedic melodramas Slaves in Algiers; or, a Struggle for Freedom (1794) and The Female Patriot; or, Nature’s Rights (1795); the opera The Volunteers (1795); and The American Tar, or the Press Gang Defeated (1796). Philadelphia-born James Nelson Barker (1784-1858) began writing plays while a teenager. Like Rowson before him, Barker did not hesitate to write across genres and focused almost exclusively on the American experience. He too found a home at the Chestnut, where his earliest works—the social comedy Tears and Smiles (1807) and the romance The Indian Princess (1808)—were staged. These plays did well enough, but the tragedies Marmion (1812) and Superstition (1824) were among his more successful works. Tragedies by Robert Montgomery Bird (1806-54) were also well received, particularly The Gladiator (1831), produced by noted Philadelphia thespian Edwin Forrest (1806-72). Organized around a Roman slave revolt, this play has been read as a commentary on the nature of slavery in late antebellum American society. With a nod to Horace, Bird chose satire to critique contemporary Philadelphia society for the theater-going public. His The City Looking Glass (1828) makes light of the attempts of a confidence man to play social reputations against each other to his benefit. The protagonist’s efforts to advance his own social standing through marriage, and to disparage the reputations of those around him, reflected a larger trend in Philadelphia drama of that period. Although Forrest produced all of Bird’s plays, their personal relationship disintegrated over a dispute about whether Bird was being fairly compensated for his playwriting.

Social and Political Rank

From the twentieth century onward, plays set in Philadelphia, by local writers or others, devoted pronounced particular attention to rank: be it social, political, or some combination of the two, often in the setting of the American Revolution. Period plays included Brooklyn-born Louis Evan Shipman’s (1869-1933) Revolutionary War-era comedy D’Arcy of the Guards (1901); The First Lady in the Land (1911) by Indiana-born Charles Frederick Nirdlinger (1862-1940), set during the highly contested presidential election of 1800; Valley Forge (1934) by native Pennsylvanian Maxwell Anderson (1888-1959), a verse play set in the brutal winter of 1778; and the Tony Award-winning musical 1776 (1969). These plays all concern political figures and portray a vibrant city, rife with intrigue. Although 1776 was not the first Broadway effort at dramatizing the War for Independence (Rodgers and Hart, for example, completed The Dearest Enemy in 1925), it became one of the most enduring. The action follows Jefferson, Adams, and Franklin as they attempt to make their case for violent revolution. Often treating the Founding Fathers with humor, 1776 remained a popular show for revivals.

Gore Vidal (1925-2012) brought a heaping dose of cynicism into the Philadelphia political play. His The Best Man (1960), set in Philadelphia and mirroring Vidal’s criticism about the 1960 political party conventions, proved very popular and was made into a feature film (1964). Although not strictly speaking a history play, The Best Man is a commentary on character assassination as a tool of anti-intellectualism and a cautionary tale about marginalizing party stalwarts who possess any degree of integrity.

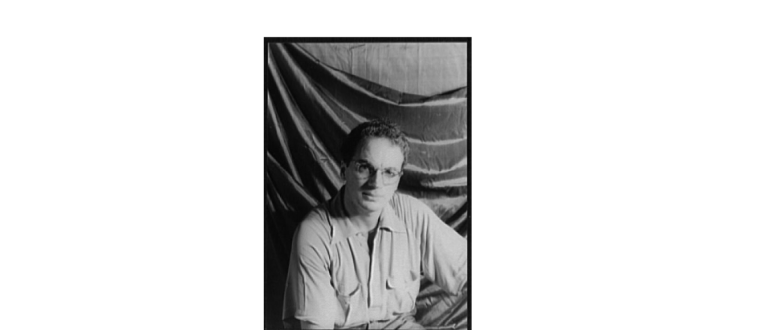

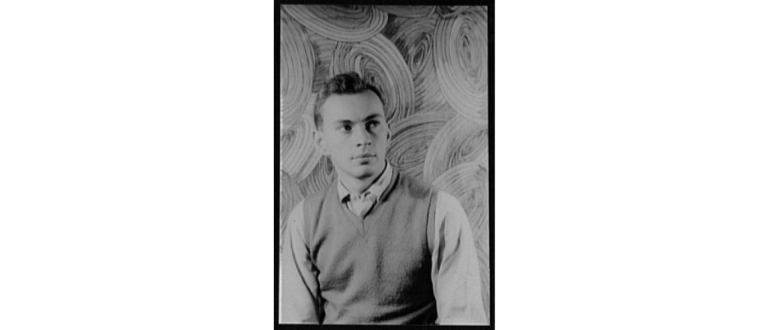

In addition to plays with political themes, Philadelphia served as a setting for dramas that explored working-class experience with a new, heightened realism. Chief among the playwrights to write about this previously marginalized America was Clifford Odets (1906-63). Born in Philadelphia to immigrant parents, his relationship with New York’s celebrated Group Theatre resulted in some of the most influential plays in the twentieth-century canon of American drama, including Waiting for Lefty (1935), Awake and Sing! (1935), and Golden Boy (1937). However, there was little room for “agitprop” (agitational propaganda) realism in plays set in the city at this time. Philadelphia native George Kelly (1887-1974) got his start writing and performing one-act skits on the vaudeville circuit, but he eventually turned those bits into full-length plays. Although Kelly became best known for his Pulitzer Prize-winning Craig’s Wife (1926), The Show-Off (1924), set in North Philadelphia, is among his most revived plays.

The Philadelphia Story

In Kelly’s plays, as with Odets’s, those who undertake physical labor might be honored, but they are seldom rewarded. Riches are reserved for the dreamers, setting something of a standard for the screwball comedies that became most associated with Philadelphia despite having been written by non-local playwrights. The Philadelphia Story (1939), written by Philip Barry (1896-1949) for Bryn Mawr alumna Katharine Hepburn (1907-2003), placed Hepburn in the role of Tracy Lord, a Main Line socialite. The play resurrected Hepburn’s career, provided her first Broadway hit, and established Barry as a major presence on Broadway. Some years later, The Happiest Millionaire (1956) by Kyle Crichton (1896-1960) tread a similar path with some success. Based on My Philadelphia Father (1955), a biography about Colonel Anthony J. Drexel Biddle (1874-1948), the play features alligators in the mansion and lavish parties tempered by service to country and loyalty to family.

Several local writers contributed to a more diverse landscape of American theater through their association with the Yale School of Drama (established 1955) and the advent of the Off Broadway movement, also in the 1950s. Classmates Albert Innaurato (b. 1947) and Christopher Durang (b. 1949), both with Philadelphia-area connections, collaborated on The Idiots Karamazov (1974) while at Yale. Durang’s comedy Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike (2013) is set in Bucks County, and the Innaurato comedies Gemini (1977) and Passione (1980) both bring working-class South Philly to the stage. Bruce Graham explored an urban terrain similar to Innaurato’s in the comedy Burkie (1984), the political satire Belmont Avenue Social Club (1993), The Philly Fan (2004), and North of the Boulevard (2012).

The Black Arts Movement also found theatrical expression in Philadelphia, especially through Freedom Theatre, which emerged as a prominent voice on the local and national theatrical scenes following its founding in 1966. Located beginning in 1968 in the former home of Philadelphia actor Edwin Forrest, Freedom Theatre produced plays by local writers, including works by co-founder John E. Allen, Jr. (1934-92), whose Clara’s Ole Man is set in South Philly; the city’s first Poet Laureate, Sonia Sanchez (b. 1934); Ed Bullins (b. 1935); Bill Gunn (1934-89); and Charles Fuller (b. 1939), who was awarded the 1982 Pulitzer Prize for Drama for A Soldier’s Play. The action of Fuller’s play opens with the mysterious murder of Sergeant Walters by two gunshots, which come from offstage. Captain Davenport arrives to investigate the murder and is immediately exposed to the racism on the base. After being told that a black officer will never be allowed to arrest a white solider, should the murderer prove to be white, Davenport interviews several soldiers before one comes forward as a witness to the murder. The suspenseful nature of the play, coupled with its commentaries on the racial politics of the United States, made it an enduring classic, widely revived throughout the country.

The Foundry and Emerging Playwrights

Freedom Theatre was among the first companies to support local talent, but not the last. In 2012, Michael Hollinger (b. 1962), Quinn Eli, and Jacqueline Goldfinger launched The Foundry, providing creative and business mentoring for local emerging playwrights. Hollinger’s playwriting credits include Ghost-Writer (2011), Opus (2006), and Red Herring (2000), all winners of the Barrymore Award, given annually for excellence in professional theater in Greater Philadelphia. A writer of long- and short-form drama, Eli became perhaps best known for plays confronting racial and sexual stereotyping, including the satire Hot Black/Asian Action (2006) and My Name is Bess (2006), which won top honors at the Trustus Playwrights’ Festival in Columbia, S.C. Goldfinger authored Skin & Bone (2014), The Oath (2009), the terrible girls (2011) and the Barrymore Award-winning Slip/Shot (2012). Several of Goldfinger’s plays premiered in Philadelphia at Azuka Theatre, which along with InterAct Theatre and other local companies, encourage new playwriting. Azuka, founded in 1999 with a mission to give “voice to the people whose stories go unheard,” earned LAMBDA and Barrymore awards. InterAct Theatre Company, founded by Seth Rozin in 1988, focused on curating new plays. Rozin, perhaps best known on the local theater scene for his award-winning directing, also wrote several plays: the comedy Men of Stone (2001), Missing Link (2000), the satire Black Gold (2007), Two Jews Walk into a War (2011), and The Three Christs of Manhattan (2015).

Rozin’s direction of 6221: Prophecy and Tragedy (1993) introduced Thomas Gibbons—and contemporary historical drama—to a wider audience. This piece, dramatizing the MOVE organization and the 1985 bombing that occurred in West Philadelphia, was the first of several historical dramas by Gibbons, who subsequently became a playwright-in-residence at InterAct. Gibbons’s other topics included a consideration of artificial intelligence, in Uncanny Valley (2015), and the battle for the Barnes collection in Permanent Collection (2003). A. Zell Williams, awarded the Philadelphia Theatre Company’s Terrence McNally New Play Award for The Urban Retreat (2016), also found a home with InterAct. The company produced the Barrymore Award-winning Down Past Passyunk (2014), dealing with bigotry and cheesesteaks, and In a Daughter’s Eyes (2011). The plays of James Ijames also reflected historical events and trends. The Most Spectacularly Lamentable Trial of Miz Martha Washington (2014) showcases Ijames’s technique of problematizing historical figures and presenting his characters with apparently insoluble moral questions. His plays frequently cross lines of generic and stylistic convention, engaging audiences in the questions with which the characters themselves must struggle. Similarly, Colman Domingo (b. 1969) explores the impact of Alzheimer’s on a West Philadelphia family in his comedy Dot (2016).

A new outlet for playwriting in the city emerged in 1997 with the founding of the Philadelphia Fringe Festival (later renamed FringeArts), which often featured works set in the city by new artists. Bucks County’s Bruce Walsh (b. 1977) earned a reputation as the leading site-specific theater maker both on his own and in collaboration with other area practitioners. Works include The Wounded Body (2000); The Guided Tour (2004), set aboard a Philadelphia trolley; Northern Liberty (2005); Old Bill (2005); Whiskey Neat (2009); and Chomsky vs. Buckley (2012).

The city continued to nurture new talent and serve as a setting for local and non-resident playwrights. Although the city’s role as a dramatic locale changed over time, sociopolitical concerns remained central to works set in the city and written by Philadelphians.

Elizabeth Mannion’s publications on modern drama include The Urban Plays of the Early Abbey Theatre: Beyond O’Casey (Syracuse University Press, 2014). Kenny Roggenkamp is an adjunct professor of English at the County College of Morris in Randolph, New Jersey, and an alumnus of Villanova University’s English Department.

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Free Library of Philadelphia Theatre Collection

- Edwin Forrest: A Legend of American Theater (Philly History Blog)

- Chestnut Street Theatre (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- The Fair Penitent, by Nicholas Rowe (Google Books)

- The Prince of Parthia, by Thomas Godfrey (Archive.org)

- Marmion; Or, Floddon Field, by James Nelson Barker (Google Books)

- The Life and Dramatic Works of Robert Montgomery Bird (Archive.org)

- The First Lady of the Land, by Charles Frederick Nirdlinger (Archive.org)

- Philadelphia Young Playwrights

- The Foundry

- Philadelphia Dramatists Center