Railroads

By John Hepp | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

The history of the railroad industry in the United States and the growth of the Greater Philadelphia region are inextricably linked. Philadelphia money and engineering built the national network and, from the middle of the nineteenth century to the middle of the twentieth, railroads helped make and maintain Philadelphia as a “Workshop of the World,” the nation’s largest manufacturing center. Within the region, freight and passenger lines helped define industrial and residential development patterns that still remained in the early twenty-first century.

The region’s first rail freight carrier, the Leiper Railroad, began service in Delaware County in 1810. Built by Thomas Leiper (1745-1825) to link his quarry with a stream so that the stone could be transported to Philadelphia, the horse-drawn tramway was replaced by a canal in 1828. Many historians consider this to be the first true railroad in North America because all previous lines had been built in connection with temporary projects and were intended to be abandoned once the projects were completed.

Initially railroads in Britain and the United States were like the Leiper Railroad, short-distance solutions for carrying freight when canals were impractical or too expensive. Beginning with the Stockton & Darlington Railway in 1825, however, British industrialists began to build railways to haul both freight and passengers over longer distances, and this concept quickly came to the United States. The first of these new railroads in the United States, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad chartered by Maryland in 1827 to link Baltimore with the Ohio River, began limited operation in 1830.

Other Cities Develop Rail Systems

The Baltimore & Ohio spurred most of the other major Atlantic seaboard cities to develop railroads. In 1830, New Jersey authorized the Camden & Amboy Railroad and Transportation Company to link Philadelphia with New York City. The next year, Pennsylvania granted charters to the Philadelphia & Columbia Railroad, the Philadelphia & Delaware County Railroad, and the Philadelphia, Germantown & Norristown Railroad (PGN). The PGN, the first to be completed, began operation within Philadelphia County in 1832.

In urban areas, railroads competed with people, horses, and wagons for the right-of-way on busy streets. Especially after steam locomotives replaced horses, railroads running down the center of streets caused a great deal of fear and controversy in Philadelphia and other municipalities. In response to public protests, Philadelphia banned steam locomotives from its streets in 1838. One result of this ban was that passenger stations moved outside the city’s pre-1854 boundaries (river to river, between Vine and South Streets) to suburbs such as West Philadelphia and the Northern Liberties.

Through the 1840s, most railroad companies operated a single route–either a passenger line like the PGN or a freight line such as the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad (the Reading), which was chartered in 1833 and transported anthracite coal to Philadelphia from the mines of northeastern Pennsylvania. A new vision for railroads came to the region in 1846 with the founding of the Pennsylvania Railroad, an integrated system that served a massive section of the nation.

From its headquarters in Philadelphia, in the second half of the nineteenth century the Pennsylvania Railroad acquired and built the lines that became a system stretching from New York to Washington (the Northeast Corridor) and west via Pittsburgh to Detroit, St. Louis, and Chicago. Although the Pennsylvania was a trunk line railroad that hauled passengers and general freight, the majority of its revenue came from carrying bulk commodities like bituminous coal and iron ore to industrial cities. The self-proclaimed “Standard Railroad of the World” operated a main line from New York to Chicago known as the “Broad Way” because it had a minimum of four tracks by the early twentieth century. In 1912, the railroad named its premier passenger train between New York and Chicago (via Philadelphia) The Broadway Limited, a name that continued to be used by the Pennsylvania and its successors until 1995.

Regional Railway Competitors

On a national scale, the Pennsylvania competed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries with the Baltimore & Ohio (based in Baltimore but essentially serving the same region) and the Erie and the New York Central systems operating from New York. These four companies made up the major freight and passenger carriers in the Middle Atlantic and Midwestern regions when these areas were America’s industrial heartland. Like most American railroads, all four of these carriers hauled far more freight than passenger traffic. Philadelphia, like New York and Baltimore, was a major international port where shipping lines interchanged cargo from Europe and Latin America with the railroads.

The Pennsylvania’s main competitor in the Greater Philadelphia area, however, was the Reading, headquartered for its entire existence in Center City within walking distance of the offices of the Pennsylvania. The Reading spent its first four decades (from 1833 to 1870) hauling anthracite from central Pennsylvania to Philadelphia, but when the lawyer Franklin Benjamin Gowen (1836-89) became its president for the first of three occasions between 1870 and 1886, everything changed. Gowen wanted to build an integrated anthracite conglomerate that mined, shipped, and sold coal from Boston to Chicago. The fact that Pennsylvania law prohibited this was but a minor inconvenience to him. Gowen extended the Reading to New York, Allentown, Bethlehem, and Harrisburg. One of his successors in 1890s, Archibald McLeod, achieved Gowen’s dream of a railroad that stretched (on paper) from Boston to the Midwest, albeit briefly. Although the terms of both Gowen and McLeod ended in bankruptcy for the company, the reorganized Reading proved an effective regional competitor for the Pennsylvania for the remainder of its existence.

Both the Pennsylvania and Reading railroads exercised great political power throughout the region and the nation. For most of the second half of the nineteenth century, the Pennsylvania Railroad effectively controlled the state legislature in Harrisburg. Gowen, while president of the Reading, had himself appointed a special prosecutor of the Molly Maguires, who had allegedly acted against the railroad’s coal subsidiary. In a city and a state known for corruption, the railroads were wealthy corporations willing to spend to obtain what they wanted. By the early twentieth century, broad public disgust with corporate excess and corruption led to Progressive Era reforms that limited railroad power and earnings.

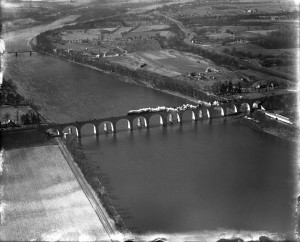

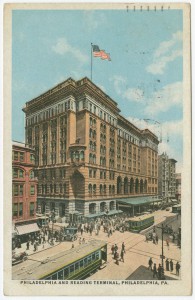

Growth of the Railway Web

During the last third of the nineteenth century, the railroads assisted in the dramatic physical transformation of the region. By 1900, the Pennsylvania, Reading, and Baltimore & Ohio (which extended its line from Baltimore to Wilmington and Philadelphia in 1886) had built an intricate web of lines that offered passenger service to virtually every community within thirty miles of Philadelphia in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware. The busiest lines had frequent and regular service all day long. The railroads also built large freight yards in the major cities and smaller yards in almost every town of any size. The massive Port Richmond terminal of the Reading in northeast Philadelphia included a freight yard along with coal and grain transfer facilities. All three systems built impressive passenger terminals in central Philadelphia that served as ceremonial gateways to the city. The main stations of the Pennsylvania (Broad Street, which opened in 1881 and was expanded starting in 1892) and the Reading (Reading Terminal, opened in 1893) helped to spur development in Center City and the surrounding neighborhoods. The elevated approaches to these stations (especially the viaduct to Broad Street Station known as the “Chinese Wall” to Philadelphians) also hindered development in portions of city as they divided the urban landscape much the way expressways do today.

By the final decade of the nineteenth century, the Greater Philadelphia area was served by two integrated railroad systems that defined a region stretching from Atlantic City to Harrisburg and from Allentown to Wilmington. The Pennsylvania was a national trunk line that served the entire region except for the Lehigh Valley, while the Reading was a regional system that allied closely with the Baltimore & Ohio and New York Central to provide national services.

Change, both regulatory and technological, soon threatened both systems and railroads nationwide. As the country’s first large-scale private enterprises, railroads caused safety and financial concerns that led the industry to be regulated on both the state and national levels beginning in the late nineteenth century. At first railroads successfully fought many of these regulations but slowly accepted them. By the early twentieth century, power shifted from the railroads to the government. Federal and state agencies issued regulations that affected safety and pricing, and these rules often limited corporate earnings.

Around the same time that regulation began, technological changes created increased competition. First came electric trolleys, which carried passengers, some freight, and even mail in cities and the surrounding countryside. By the first decade of the twentieth century, the Pennsylvania concluded it could not compete with trolleys for short-distance riders and abandoned or downgraded its stations within five miles of Center City Philadelphia. To lessen expenses, the Pennsylvania also electrified its two busiest commuter lines in the region, to Paoli and Chestnut Hill. After World War I, automobiles, buses, and trucks operating on taxpayer-paved streets and highways began to compete more effectively with the railways for a wide variety of traffic. More passenger lines in the region were abandoned, and this process accelerated in the Great Depression. Ridership declined so rapidly in southern New Jersey that the Pennsylvania and the Reading merged their competing lines between Camden and the Jersey Shore into one company in 1933 under pressure from the state government.

Twentieth-Century Declines

Passenger and freight traffic continued to decline in the 1920s and 1930s despite innovations such as mainline electric passenger and freight trains on Pennsylvania (eventually linking Philadelphia with Harrisburg, Washington, and New York), further electric commuter lines on the Pennsylvania and the Reading, the Reading’s stainless-steel Crusader between New York and Philadelphia, and two new Pennsylvania passenger stations—Broad Street Suburban Station and Pennsylvania (Thirtieth Street) Station. World War II reversed this trend temporarily, but after the war the declines resumed. The 1950s also saw an expansion of the airline industry, which adversely affected the railroads’ long distance passenger traffic. As losses mounted, more trains were abandoned and all railways in the region accelerated their conversion from steam to less-expensive-to-operate diesel locomotives. The Baltimore & Ohio abandoned all its passenger service between New York and Washington via Philadelphia in 1958.

In 1968, the Pennsylvania merged with the New York Central to form the ill-fated Penn Central. The Penn Central, headquartered in Philadelphia, declared bankruptcy just two years later. It was the nation’s largest railroad and its bankruptcy was the largest in American history at the time. As one consequence of the Penn Central debacle, many other struggling Mid-Atlantic railways became insolvent (including the Reading). In 1971, the National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) took over most intercity passenger trains in the region (except for the Reading’s), while in 1976 the Consolidated Rail Corporation (Conrail) acquired the region’s freight trains and commuter trains from Boston, New York, and Washington to Chicago and St. Louis. Conrail took over the operation of virtually all lines in Philadelphia, except for the freight-only line of the Baltimore & Ohio. Amtrak maintained an operational hub in Philadelphia, which also became the headquarters city for Conrail.

Philadelphia’s decline as a national railroad center began in 1998 when Conrail was purchased by its two main competitors: CSX and Norfolk Southern. Although Conrail continued to operate in certain areas (including Greater Philadelphia) as a jointly-owned switching line, for the first time since the 1830s no major railroad company was headquartered in the city. A few years later, in the early twenty-first century, Amtrak dramatically cut back the trains it originated in Philadelphia.

At the start of the twenty-first century, a wide variety of railroad operations served the Greater Philadelphia region. Commuter trains were run and funded by state agencies such as DART First State, New Jersey Transit, and the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) over an area that stretched from Trenton, New Jersey, to Newark, Delaware, and from Atlantic City to Thorndale, Pennsylvania. In addition to the Northeast Corridor service between Boston and Richmond, Virginia, Amtrak provided long-distance passenger trains north to New England, south to Florida and New Orleans, and west to Pittsburgh. CSX and Norfolk Southern used the city as a hub on the national rail freight system. Conrail and a number of short-line railroads provided local freight service throughout the region. The ports in the region still generated a great deal of freight traffic for the railroads as the Philadelphia area continued to compete with Baltimore and New York as a gateway for international traffic. Although Philadelphia remained an important regional transportation hub, the city was no longer a center of national importance to the railway industry.

John Hepp is Associate Professor of History and co-chair of the Division of Global History and Languages at Wilkes University in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, and he teaches American urban and cultural history with an emphasis on the period 1800 to 1940. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Railroads agree to slow down crude oil trains in major cities (WHYY, February 21, 2014)

- Lawmakers focus on rail safety as more oil trains to move through Pa. (WHYY, March 6, 2014)

- Railroads stress safety after deaths up in 2013 (WHYY, April 8, 2014)

- Vintage railroad again on track to bring prosperity to Pa. towns (WHYY, December 29, 2014)

- CSX and Kenyatta Johnson announce plans to rebuild 25th Street viaduct (WHYY, April 8, 2015)

- Expert assesses risk of oil train accidents in Pennsylvania (WHYY, August 17, 2015)

- Passenger train service on Northeast Corridor could get a lot faster (WHYY, January 12, 2016)

- One year after Amtrak 188 derailment, where does region stand on Positive Train Control? (WHYY, May 12, 2016)

- Amtrak engineer surrenders on charges in fatal crash (WHYY, May 18, 2017)

Links

- The Railroad in Pennsylvania (ExplorePAHistory)

- Railroad Museum of Pennsylvania

- The Pennsylvania Railroad Technical & Historical Society

- Amtrak: A History of America's Railroad

- De Luxe: The Tale of the Blue Comet (Vimeo)

- Stereographs of Pennsylvania Railroad Views (Digital Exhibit, Library Company of Philadelphia)

- Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Photograph Album (Digital Exhibit, Library Company of Philadelphia)

- The Rail Park