Row Houses

By Amanda Casper | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

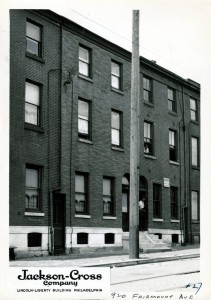

Lining Philadelphia’s straight, gridiron streets, the row house defines the vernacular architecture of the city and reflects the ambitions of the people who built and lived there. Row houses were built to fit all levels of taste and budgets, from single-room bandbox plans to grand town houses. The row house was easy to build on narrow lots and affordable to buy, and its pervasiveness resulted in Philadelphia becoming the “City of Homes” by the end of the nineteenth century. As Philadelphia emerged as an industrial epicenter, the row house became synonymous with the city and was held up as an exemplar for egalitarian housing for all.

From Philadelphia’s founding, the row house has served as an easy solution to housing the city’s residents. As ambitious colonists began to break up the big city blocks of William Penn’s “greene country towne” with secondary streets, alleys, and courts, speculative developers and builders constructed rows of houses that matched varied budgets and taste. In many American cities, including New York, Baltimore, Providence, and Washington, D.C., builders, developers, and residents used row houses to solve the problems of housing demand, steep land prices, and narrow lots. However, Philadelphia’s unique combination of original city planning, expansive geography, and the simultaneous trend of speculative building meant street (or court)-front land was obtainable by builders or modest investors at an easier rate compared to other major urban centers. As a result, Philadelphia’s streets, alleys, and courts were lined with relatively homogenous structures of predictable form and design. By the nineteenth century, the term “Philadelphia row” not only became synonymous with the landscape of the city, but it also became a term used elsewhere to describe orderly rows of regularized houses.

Constructing houses in a row was cost-effective and efficient for builders. It allowed them to replicate a design from only a few plans, consolidate crews and resources at one site, and buy materials in bulk. The shared party walls of row houses also meant less stone or masonry work compared to a free-standing house. For piping sewer, plumbing, and gas lines, such specialized and expensive work could be done for the entire row at one time, saving labor costs. Little changed between the houses as builders completed them down the street for eventual sale.

Georgian Construction

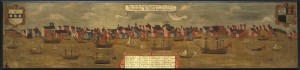

The earliest Philadelphia row houses reflected the building traditions of English settlers who, because of the devastating fire of 1666, embraced the fire-resistant, Georgian construction that was efficient in the city’s narrow lots. The first recorded group of row houses was Budd’s Row, a speculative development of ten buildings constructed around 1691 in present-day Old City, since demolished. Using medieval half-timber construction that was later banned, the houses were two stories high and two rooms deep. Except for cases like Budd’s Row, brick quickly became the standard material for construction. As the city expanded in the later eighteenth and nineteenth century and speculative development increased, the streets filled with orderly rows of houses.

As Philadelphia rapidly expanded after the Civil War, the row house served as the standard form used by builders to fill in new neighborhoods. In 1891, editors of the nationally-circulated Harper’s Weekly understood that the “typical Philadelphia home” was a row house, and included illustrations of an ornamented brick row house with front porch alongside a more humble version, implying for the magazine’s audience that the row house could house both working- and middle-class residents. In 1893, city promoters embraced this characterization when, at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, they constructed a simple brick row house described as a “model Philadelphia house.” The cost for such a building was approximately $2500.

For reformers and city promoters, the row house also presented social and economic benefits for the city and its residents that they often emphasized. The relatively low cost of $2,500 to purchase a modest row house reminded visitors at the Exposition and readers of catalogs and magazines that the dwelling was affordable for most, and Philadelphia was well-known for its high rate of homeownership. The row houses’ popularity in Philadelphia consequently earned it the slogan the “City of Homes.” However, many contemporaries also correlated homeownership with public health and safety. Many also argued that high homeownership rates helped to cultivate a more “contented” labor force in Philadelphia than in other cities like New York and Chicago. Ideologically, the row house and the homeownership it enabled had broader implications for the culture of the city and the way it was promoted on a national level.

Row Houses and Neighborly Bonds

The inherent interconnectedness of row house construction—with shared walls and close proximity—had lasting consequences for Philadelphians who would own and live in them. In Philadelphia neighborhoods tightly packed with row houses, the problems of one building could easily spread to others. City leaders planned for obvious calamities like fires by requiring tall masonry party walls that rose above rooflines, meant to stop potential fires from spreading from house to house. However, flooded basements, unwanted infestations, structural failures, and even explosions that plagued one house could easily impact the immediate neighbors, and at times spread across streets and alleys impacting surrounding residents. Row house living at its best was an intimate one that encouraged strong neighborly bonds; it could also present unintended problems.

Throughout Philadelphia’s history, row houses captured the ambitions of city leaders and residents. The row house serves as evidence of residents’ defiance of the green country town that William Penn envisioned. Easy to construct and affordable, the row house enabled a high rate of home ownership and thus earned its place as a symbol of the city’s landscape.

Types of Philadelphia Row Houses

A survey of row house types found in the historic neighborhoods of Society Hill and Old City, compiled by architectural historian William J. Murtagh in 1957, remains a definitive starting point for understanding the plans of row houses in Philadelphia. Murtagh divided the plans of Philadelphia row houses into four types: the bandbox house (trinity) and the more elaborate London house, city house, and town house plans. Each type accommodated varied degrees of economic means and social ambition.

- The bandbox (sometimes called a trinity) is the smallest and therefore cheapest to construct, and it normally served as housing for the working-class or servants of larger properties nearby. These homes were often constructed on courts behind larger properties or in narrow alleys that divided larger blocks. The bandbox is typically no larger than sixteen feet on any side, with one room on each floor, rising two or three stories with enclosed winding stairs. The privies, or “necessaries,” were normally at the rear of the courts. In 1948 Murtagh found more than twenty courts filled with Bandbox row houses in Society Hill, but many were later demolished. Bell’s Court off Saint Josephs Way and Bladen’s Court off of Elfreth’s Alley are two examples that survived into the twenty-first century.

- The London house plan is more elaborate than the bandbox plan, with more rooms and an arrangement that permitted privacy and formality. It typically is two rooms deep, providing more space, and has a side hall, which enables privacy for the front room. Winder or straight stairs separate the front and back rooms. The London plan takes advantage of the common long and narrow Philadelphia lot. The London examples most often date to the nineteenth century, when they became more popular amongst speculative builders. One of the earliest surviving examples of a London plan is Carstairs Row, constructed between 1801 and 1803 on the south side of Sansom Street (later known as Jeweler’s Row). It imitated the grand, uniform terraces of Europe that became increasingly favored by Philadelphians in the nineteenth century. The houses of Marshall’s Court (405-11) constructed in 1810 reflected a modest London plan; since demolished, they were extensively recorded by the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS).

- The city house plan is an elaboration on the bandbox plan. This plan includes a front room like the bandbox, but the stairs are separated in a piazza, and stretching out behind are ancillary service rooms for cooking and laundry. The back rooms are narrower than the lot, resulting in a side yard with windows for light and ventilation. Like the other plans, rear access was achieved with a passage between houses. In many rows, the end house was more elaborate than its neighbors; for instance, on Marshall’s Court all were simple London-plan row houses except for 403, which was a city house plan. Several houses on Elfreth’s Alley also use the city house plan, including numbers 113, 115, 130, and 132.

- Lastly, the town house plan is an expansion of the London house plan and similar to the city plan, but larger and often more elaborate in detail. The plan is divided into front and rear sections. The front section is the full width of the lot and typically has two rooms with a hall leading to straight stairs. The front section is normally divided from the rear with a piazza that holds a secondary set of stairs. Like the city house plan, the rear section has narrower back service rooms that extend towards the back of the lot. The rear yard was sometimes developed into a court of bandboxes, but otherwise housed a stable and coach house, accessed by a rear alley. There are many well-known examples of rowhouses with the town house plan, including the Powel House, 244 S. Third Street.

Amanda Casper is a PhD candidate in History at the University of Delaware. She has a M.S. in Historic Preservation from the University of Pennsylvania and a M.A. in History from the University of Delaware, and she has worked for the National Park Service Northeast Regional Office and at several historic sites throughout Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Amidst A Redeveloping Waterfront, An 1830s Row Lives On (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- The Quintessential Object of Industrial Philadelphia (PhillyHistory.org Blog)

- Funeral for a Home (Temple Contemporary)

- Heartbreaking Photos of Lonely Row Houses (The Atlantic Cities)