Saint Patrick’s Day

Essay

In March, Philadelphians of many backgrounds join together to celebrate Saint Patrick’s Day, the city’s Irish citizens, and their heritage. Celebrated in Philadelphia since 1771, the holiday began as a Catholic holy day and evolved into a rambunctious affair marked throughout the region by parades, music, dancing, drinking, and wearing kelly-green clothing to symbolize the Irish flag. Over time, Saint Patrick’s Day reflected political, religious, military, and secular themes as Philadelphia became a hub for Irish immigrants and generations of Irish-American families.

The holiday is named for Saint Patrick, born around 387 CE in Roman-controlled Britain, who is credited with bringing Catholicism to Ireland in the early fifth century. As a bishop, Patrick traveled the island for decades to convert former pagans and druids to Catholicism and create churches. After his death in 461 CE, Patrick was canonized and Catholics observed his death day, March 17, as his feast day, or day dedicated to his memory. As time passed, Patrick became known as the patron saint of Ireland, believed to take special care of the Irish from his place in heaven. His feast day became a holy day of obligation (to attend Mass) for Catholics in Ireland. By the seventeenth century, as Protestant settlers from Britain continued to gain control in Ireland, Saint Patrick and his feast day were bound to Irish-Catholic identity and pride. Emigrants from Ireland carried these traditions with them to the New World.

The Irish were among the earliest immigrants to Philadelphia. Although the highest numbers of Irish arrived during the years of the potato famine (1845-52), Irish Philadelphians contributed to social and cultural life in the city before and during the American Revolution. On March 17, 1771, a group of Irishmen founded the Society of the Friendly Sons of St. Patrick for the Relief of Emigrants from Ireland, a civic organization dedicated to helping Irish immigrants and celebrating their patron saint by hosting a dinner each March 17. Members of the society included Commodore John Barry (1745-1803) and General John Cadwalader (1742-86). President George Washington (1732-99) was made an honorary member in 1782, in recognition of his decree on March 16, 1779, that his troops, many of them Irish, were to take Saint Patrick’s Day off to celebrate and rest after a long, harsh winter at war.

Political Overtones

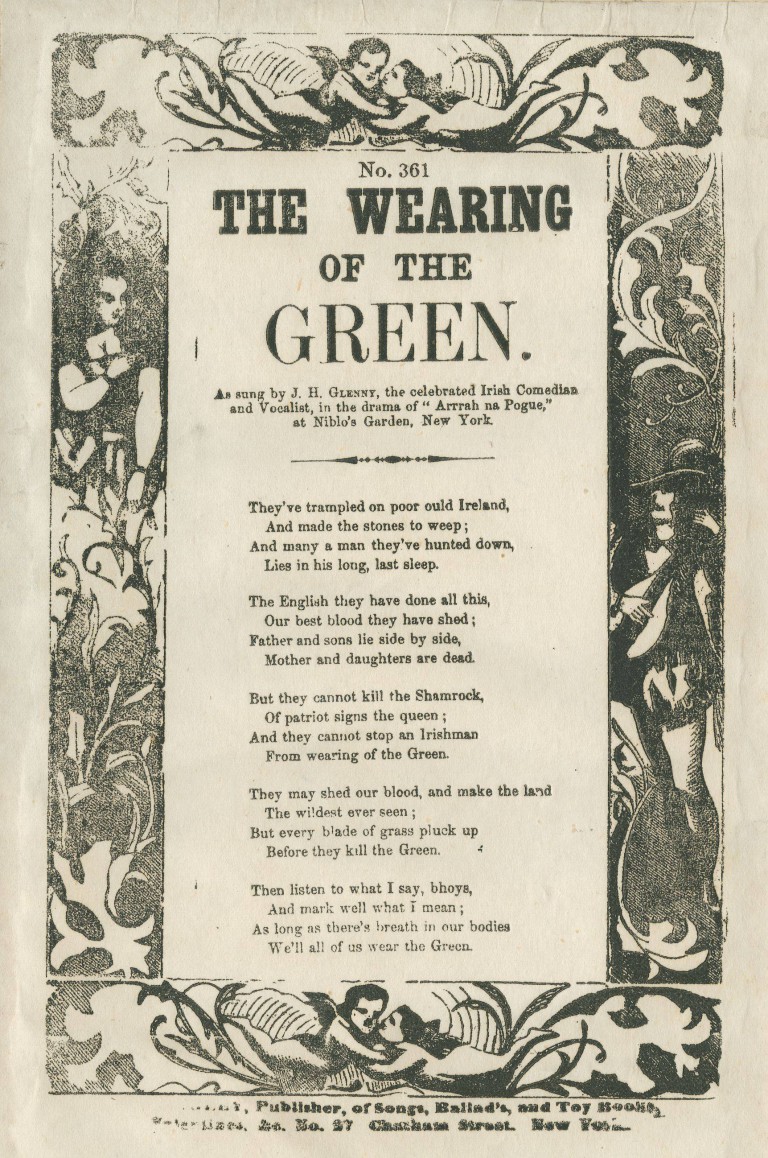

In the early nineteenth century, the Friendly Sons’ annual dinner gained popularity as the Irish immigrant population grew. The event also gained political overtones amid anger over English oppression of the Irish back home and fierce pride in a new, free American identity. By the 1830s, March 17 celebrations included rallies against English rule of the motherland and appeals to attendees to use their American liberty to secure rights for others. In 1837, from the steps of the Franklin Institute on Seventh Street just below Market Street, Joseph Doran urged his fellow Irishmen to “… call forth then your powers and assist your fellow citizens in preserving those liberties which you are permitted to enjoy.”

When the Great Famine, also known as the potato famine, hit Ireland in 1845 thousands of peasant farmers left for the United States. By 1850, 72,000 people of Irish descent lived in Philadelphia and the influx of often poor, Catholic immigrants met with backlash from “native” Philadelphians, who sought to protect their own social status by excluding the Irish from economic, social, and civic opportunity. By 1859, however, Irish Philadelphians began forming organizations similar to the Friendly Sons to carve places for themselves within the city. As an expression of their loyalty and respectability, many groups formed military units, a right unknown in Ireland and a symbol of their new freedom. March 17 soon became associated with military infantry and formations, as many groups wore full regalia to celebrate their heritage.

Following the Civil War, Irish Americans cited their service to the United States to prove their worth to their fellow countrymen, and anti-Irish rhetoric quieted down substantially. Parades, a popular form of entertainment in this era, became fixtures of the annual celebration. Parades drew large crowds, and the Irish took advantage of the attention to spread messages of importance to their communities and beyond. For example, the 1870 parade included temperance organizations spreading the message of abstinence from alcohol—a cause embraced by many Irish women because of alcohol-related problems within their families.

After several cancellations during the Great Depression and World War II, the Philadelphia Saint Patrick’s Day parade revived in the 1950s with greater focus on the holiday’s religious origins. Philadelphia’s Irish population had been decreasing, with fewer citizens participating in Irish-Catholic political or spiritual life, since the creation of the Republic of Ireland in 1922 and the National Origins Act of 1924. In 1952, the Saint Patrick’s Day Observance Association, organized in cooperation with the Ancient Order of Hibernians, Archbishop John F. O’Hara (1888-1960), the Catholic schools network, and other fraternal societies, began planning the first “official” Saint Patrick’s Day Parade. Conceived as a religious event, by 1954 parade rules stated first and foremost that “any group participating in the Parade must be of Catholic character.” The parade’s executive committee included political leaders, police officers, firefighters, and independent business owners, who raised funds for the event through the sale of flags and badges to participants, vendor fees, and donations from Catholic parishes. The 1953 parade, the first planned by official committee, attracted a reported 65,000 individual participants and 100,000 spectators along the parade route, which began on South Broad Street near Washington Avenue and ended on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, outside the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Parade Popularity Grows, as Do Costs

As the parade became increasingly popular, the need for increased funding conflicted with the religious roots of the celebration. Parade costs more than doubled, reaching a price tag of $7,000 by 1965. Fund-raising luncheons helped, but without business investments and city money the budget was still tight. Organizers disagreed about whether to allow businesses to advertise on floats or whether non-Irish and non-Catholic groups should participate, although diversity could draw bigger crowds. By 1978 the city’s Recreation Department made a donation and some non-Irish groups joined the parade.

By the end of the twentieth century, the parade, still run by the nonprofit Saint Patrick’s Day Observance Association, represented Philadelphia’s variety of experience with Saint Patrick’s Day. Annual luncheons, dinners, and speaking engagements drew upper-class crowds, and early-morning church services drew practicing Catholics, but the parade, beginning near City Hall, drew Philadelphians of all backgrounds to the Parkway. Live musicians and dancers, colorful floats, candy, and rows of vendors added to the revelry, and the party atmosphere tended to obscure the religious roots of the holiday. Unlike the temperance marchers of 1888, many attendees viewed alcohol consumption to be a crucial component of the day, making bar crawls or house parties popular destinations after the parade. This aspect of the holiday could be contentious, leading some to criticize the parade as a source of public drunkenness, vandalism, and underage drinking.

Philadelphia claimed the largest parade in the Greater Philadelphia area, but in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries many smaller cities and towns also celebrated their Irish heritage in mid-March. Springfield, in Delaware County, hosted an annual Saint Patrick’s Day parade, as did Levittown in Bucks County. Bucks County also became home to the six-day Newtown Irish Festival while West Chester, in Chester County, hosted a Celtic pub-crawl and businesses across the area offered specials on traditional Irish-American cuisine such as corned beef, cabbage, and potato dishes. In southern New Jersey, shore towns Atlantic City, Seaside Heights, and Wildwood hosted parades and in Burlington County, Mount Holly appointed one young women “Miss Saint Patrick” and provided her a scholarship and a prominent place in its parade.

Whether drawn by religious affiliation, Irish heritage, or the prospect of a good party, in the early decades of the twenty-first century Saint Patrick’s Day celebrators found a sense of camaraderie and shared experience among the crowds. The popular narrative of Irish perseverance in the face of adversity and the proud celebration of a resilient culture resonated with many Philadelphians, even those who did not share the same ethnicity or faith. Once a religious holiday and a political parade, Saint Patrick’s Day transformed over two centuries into a largely secular celebration reflecting the changing culture of Philadelphia’s Irish population and of the city at large.

Mikaela Maria is an editorial, research, and digital publishing assistant for The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. She received her M.A. from Rutgers University and works as a public historian and museum professional in Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University