Saws and Saw Making

Essay

Philadelphia ranked as one of the nation’s foremost saw manufacturing centers for much of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Large-scale saw making began locally in the early nineteenth century, and by midcentury a number of major saw manufacturers operated in the city, including the world’s largest, Henry Disston’s Keystone Saw Works. Disston created a unique company town around his saw works and joined other industrialists in making Philadelphia one of the world’s premiere manufacturing cities. Saw making remained strong through the mid-twentieth century, after which it went into decline, part of a broader deindustrialization of the region.

Saw making required a particularly high level of craftsmanship. Few artisans in early America possessed the technical skills needed to produce a quality saw with the right proportions of strength, flexibility, and smoothness of surface. As a result, most saws were imported. The few saw makers in the Philadelphia region in the eighteenth century included English immigrant Isaac Harrow (?–c. 1745), who advertised in 1734 that he had set up a plating and blade mill in Trenton, New Jersey, to make a wide range of tools and utensils, including saws; John Harper, who had a saw-making shop at Sixth and Cherry Streets in Philadelphia in the early 1790s and one in Trenton in 1795, but who was most notable for doing some of the earliest work for the United States Mint; and English immigrant Francis Mason (d. 1802), who first appeared in a 1799 Philadelphia directory as a saw maker on South Fifth Street and who advertised frequently in local newspapers for a few years until his death.

Philadelphia’s first successful large-scale saw manufacturer was William Rowland (1780–1857), who first appeared in a city directory as a saw maker on High (later Market) Street, near Fifth Street, in 1804. He may have previously apprenticed to Francis Mason; he appears to have occupied the same location as Mason, and in 1806 he advertised himself as “Successor of Francis Mason.” While several sources erroneously credit Rowland as America’s first saw manufacturer, more accurately, he established the nation’s first large-scale, long-running saw factory. By the 1820s Rowland had moved to Filbert Street between Seventh and Eighth Streets, where he employed twenty workers and made saws that the Franklin Institute recognized for their excellence. In 1845 Rowland began making his own steel, and by the mid-1850s he had fifty workers and was producing two hundred saws daily.

Many Small Saw-Making Shops

Rowland was one of several major saw manufacturers in Philadelphia in the mid-nineteenth century. An 1844 city directory listed twenty saw makers. Most had small shops, but within a decade a few had grown into large operations. They originally concentrated in the highly industrialized downtown area north of Market Street and east of Eighth Street, although most eventually moved to larger quarters elsewhere. Among the saw makers who opened small shops in this part of the city in the 1840s and became major manufacturers by the 1850s were Henry Disston (1819–78), who in 1840 opened a shop on Bread Street near Second and Arch Streets that later became the Keystone Saw Works; Charles Johnson (d. 1852) and William Conaway (b. 1822), who formed a partnership in 1846 that became the Union Saw & Tool Manufactory at Fourth and Cherry Streets; and Walter Cresson (1815–93), who began making saws in the late 1840s and had a shop on Commerce Street (a small street just above Market) between Fourth and Fifth Streets. In 1850 Cresson opened a saw factory on the Schuylkill River in Conshohocken, Montgomery County, while also keeping his Old City location. One of Cresson’s chief saw makers, Irish immigrant William McNiece (1844–1904), left Cresson’s employ in 1863 and with a partner established the company that became the Excelsior Saw Works at Fifth and Cherry Streets.

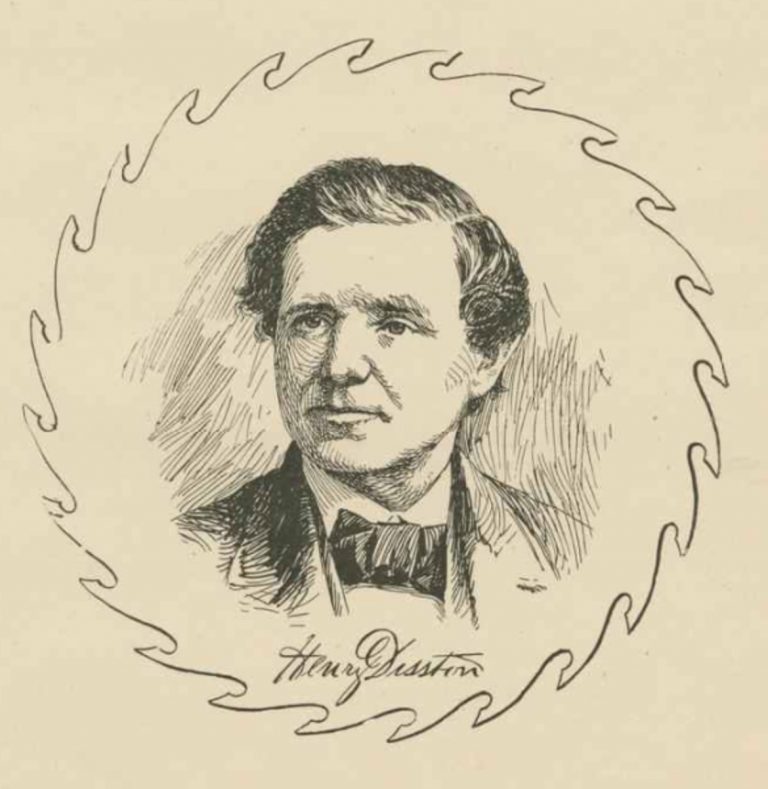

Of these leading mid-nineteenth-century Philadelphia saw makers, one—Henry Disston—emerged as the most successful, building his Keystone Saw Works into a massive enterprise that became the largest saw manufacturer in the world. Born in England, Disston came to Philadelphia with his father at age thirteen. His father died three days after arriving, however, and Henry eventually apprenticed with a local saw maker. After opening his own shop in the downtown industrial area in 1840, he moved a few times before settling in 1846 at Front and Laurel Streets in Northern Liberties, where his business prospered. A gifted mechanical engineer with an unwavering commitment to quality, Disston developed several new products and techniques in saw manufacturing, including introducing the first crucible steelmaking process in the nation in 1855. Disston actively recruited skilled workers from England’s famed Sheffield metal-working district; many of his key employees were immigrants from this area.

By the Civil War, Disston’s Keystone Saw Works had become the largest saw manufacturer in the United States, employing over 150 workers in four buildings totaling twenty thousand square feet of space. He grew his business by acquiring many of the region’s other saw manufacturers, including William Conaway’s Union Saw & Tool Manufactory in 1857, Walter Cresson’s saw works in 1865, and the successor company to William Rowland’s Saw Works in 1870. By this time, Disston had outgrown his Northern Liberties location. To accommodate his expanding operation, he purchased a large tract of land along the Delaware River in Tacony and began moving the company there in 1872.

Disston’s Huge Complex

The Disston saw works in Tacony grew to be an enormous, sprawling complex. To provide a safe, family-centered environment for his employees, Henry and his wife, Mary (1822–95), created the Disston Estate, a 158-acre tract in Tacony west of the industrial area that they designated as a residential community. The company also made a wide range of other tools, mostly notably files, which it produced in the millions annually. Within the Estate, separated from the industrial section by railroad tracks, the Disstons provided affordable housing for company workers, offering quality homes for sale or rent at reasonable prices. They also placed deed restrictions on land sold within the Estate to prohibit the sale of alcohol and the operation of factories, slaughterhouses, or other activities that would compromise the residential character of the neighborhood. (The prohibition on the sale of alcohol within the Disston Estate was upheld after a legal battle in the 1990s and remained in effect in the early twenty-first century.) Of an estimated 2,500 company towns established in the nineteenth-century United States, the only other paternalistic town of this nature within an urban area was George Pullman’s (1831–97) community in Chicago. The National Park Service designated both the Pullman District and the Disston Estate as National Historic Districts, the latter in 2016.

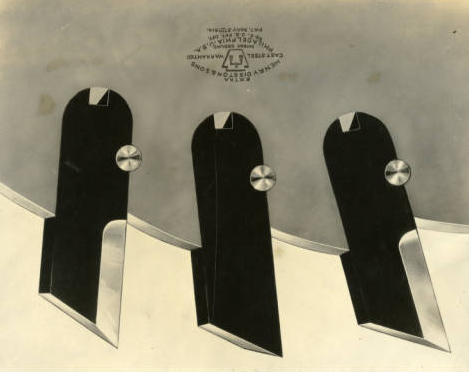

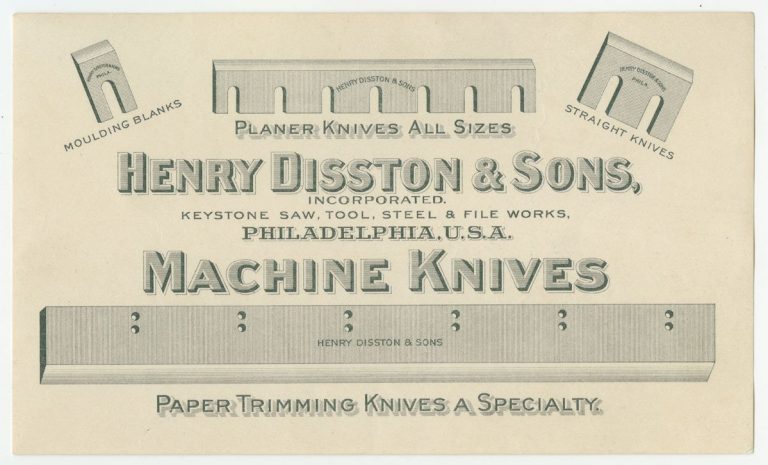

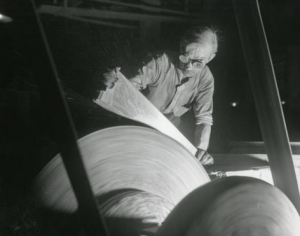

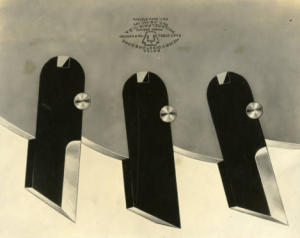

By 1909 the Disston company occupied fifty-seven buildings on fifty acres. Its four thousand workers produced nine million saws annually, from traditional handsaws used by carpenters and do-it-yourselfers to huge circular and band saws employed by the lumber industry and in industrial settings. The company also made a wide range of other tools, mostly notably files, which it produced in the millions annually.

While Disston sold its products worldwide and dominated the industry, a few smaller companies in the greater Philadelphia area made saws in the early twentieth century. The American Saw Company in Trenton, New Jersey, manufactured saws and other tools and employed fifty workers in 1901. The Alston Saw & Steel Company in Folcroft, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, specialized in making hack saws in the 1910s.

Henry Disston died in 1878 and did not live to see the vision for his company or community come to full fruition. His widow managed the Estate, while his sons and grandsons ran the company, which they incorporated as Henry Disston & Sons in 1886. It remained a profitable family-run firm until the mid-twentieth century, when, like many of Philadelphia’s heavy industries, it began to experience serious business challenges. In 1955 family members sold the firm to H. K. Porter, Inc., a holding company that largely broke up the enterprise, closing or relocating various departments and significantly reducing its scale of operations. After several subsequent ownership changes, the company continued operating, at a greatly reduced scale, at the Tacony plant into the early twenty-first century. Known as Disston Precision, in the late 2010s it employed a few dozen workers who made precision saw blades, custom metal plates, and other specialty items, using both century-old machines still in place at the plant and modern computer-driven equipment. Disston remained the only major manufacturer from Philadelphia’s late nineteenth and early twentieth-century industrial heyday still in operation in the city.

Jack McCarthy is an archivist and historian who specializes in three areas of Philadelphia history: music, business and industry, and Northeast Philadelphia. He regularly writes, lectures, and gives tours on these subjects. His book In the Cradle of Industry and Liberty: A History of Manufacturing in Philadelphia was published in 2016 and he curated the 2017–18 exhibit Risk & Reward: Entrepreneurship and the Making of Philadelphia for the Abraham Lincoln Foundation of the Union League of Philadelphia. He serves as consulting archivist for the Philadelphia Orchestra and Mann Music Center and directs a project for Jazz Bridge entitled Documenting & Interpreting the Philly Jazz Legacy, funded by the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2018, Rutgers University