Scrapple

By Mary Rizzo | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

Scrapple, which came to the Philadelphia region from Germany, is a loaf of cooked pig parts thickened with cornmeal or buckwheat usually spiced with sage and pepper. Once cooled, the loaf is sliced, fried, and served as a breakfast side dish, often with syrup. Not just a culinary transplant, scrapple exists because of the interplay of Old and New World traditions and ingredients.

As a rural tradition during hog-butchering time, scrapple dates to the sixteenth century in Germany, where it was called panhas, pawnhos, or pan haas, meaning “pan rabbit.” While parts of the pig became sausages or bacon, the rest, “everything but the oink,” was collected for scrapple and for black or blood puddings, of which scrapple is a variant. The German product did not include cornmeal, which was not available in Europe.

German immigrants to Pennsylvania, mistakenly called Pennsylvania Dutch, shared their culture with English settlers, who had similar food traditions. The English influence can be seen in the shift in the product’s name. No longer called panhaas, except in rural communities, it became scrapple (or Philadelphia scrapple) by the 1820s—at least in print.

Origins of the Name

Different explanations have been offered for the exact origins of the name. Food historian William Woys Weaver has argued that scrapple was a conflation of the German word panhaskroppel, which literally meant slice of panhas, and the English word scrapple, which referred to leftovers and to spade-shaped kitchen implements. Others have said that English-speakers came up with the name scrapple as they conjured up images of a product made with leftovers that were otherwise suspect. In fact, scrapple was a thrifty means to make sure that every edible part of the pig was used, especially during the few days when hog butchering took place. The “scrap” in scrapple does not mean low-quality parts, but merely what had not been used in making other foods, like sausage.

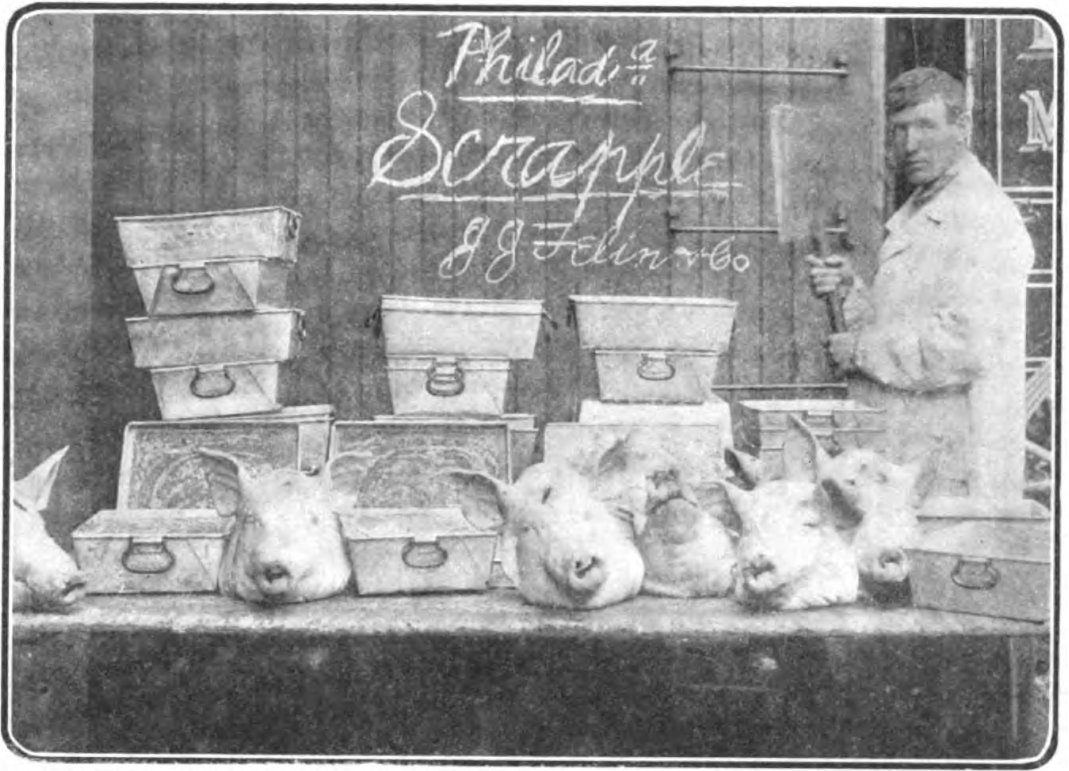

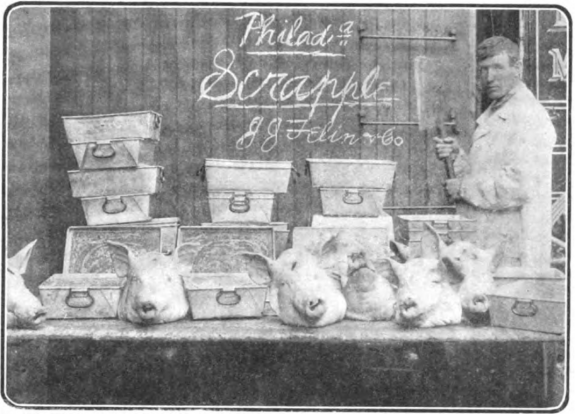

By the mid-nineteenth century, production of scrapple industrialized. The Civil War increased the need for industrialized food production; at the same time, more people were living in cities and becoming less familiar with rural food traditions. In 1863, Joshua Habersett opened Habersett Pork Products in Middletown Township, Delaware County, Pennsylvania, the first company to mass produce scrapple.

A Recipe from 1869

Cookbooks and newspapers offered home cooks advice on making the dish. Domestic Cookery, published in 1869 by Elizabeth Ellicott Lea, detailed the culinary culture of Pennsylvania Germans and the Tidewater South for “young housekeepers” who had not learned these recipes at their mothers’ or grandmothers’ knees. Its scrapple recipe was a basic one: “Take eight pounds of scraps of pork that will not do for sausage; boil it in four gallons of water; when tender, chop fine, strain the liquor and pour it back into the pot; put in the meat; season it with sage, summer savory, salt and pepper to taste; stir in a quart of corn meal; after simmering a few minutes, thicken it with buckwheat flour very thick.”

Various kinds of cooked and thickened loaves of pig parts can be found throughout the U.S. In the South, liver mush denoted the addition of pig liver, while Ohioans substituted oatmeal for cornmeal and called it goetta. Scrapple, however, has retained its deep connection to the Philadelphia region. In the early twenty-first century, festivals celebrating scrapple took place in Bridgeville, Delaware, and at the Reading Terminal Market in Philadelphia. The locavore movement, which celebrates regional cuisine, showed signs of making scrapple popular again as an edible artifact of the region’s rural roots.

Mary Rizzo is the Public Historian in Residence at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for the Humanities (MARCH) at Rutgers University-Camden. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Six Pack: Scrapple, Whether You Like It Or Not (Philadelphia Magazine)

- Scrapple is One of the Crucial American Meats (Esquire.com)

- Habbersett Inc.

- Bridgeville Apple-Scrapple Festival

- What is Scrapple and What Does it Contain? (CulinaryLore.com)

- Scrapple Dishes (What's On the Menu? New York Public Library)