Treaty of Shackamaxon

Essay

The Treaty of Shackamaxon, otherwise known as William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians or “Great Treaty,” is Pennsylvania’s most longstanding historical tradition, a counterpart to the foundation stories of Virginia (John Smith and Pocahontas) and New England (the first Thanksgiving). According to the tradition, soon after William Penn (1644-1718) arrived in Pennsylvania in late October 1682, he met with Lenni Lenape Indians in the riverside town of Shackamaxon (present-day Fishtown). There, beneath a majestic elm, they exchanged promises of perpetual friendship. The tradition may well have a historical basis in an actual treaty meeting in Shackamaxon; however, as the term “tradition” indicates, the event is not recorded in original primary source documents, and its details and very occurrence have been debated.

The treaty’s renown was amplified through literature and art. The French philosopher Voltaire (1694-1778) famously declared it “the only treaty between those people [the Indians] and the Christians that was not ratified by an oath, and was never infring’d.” (Quaker doctrine prohibited Penn from making oaths.) The painter Benjamin West (1738-1820), commissioned by Penn’s son Thomas (1702-75), created the ubiquitous emblem of colonial Pennsylvania and American Quakerism in William Penn’s Treaty with the Indians When He Founded the Province of Pennsylvania in North America (1771-72). West’s tableau (now at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts) informed early historical accounts of the treaty. It was adapted, and further popularized, in the Quaker folk artist Edward Hicks’s (1780-1845) Penn’s Treaty and Peaceable Kingdom paintings. To this day it illustrates history textbooks.

In eighteenth-century diplomatic records, Native Americans frequently invoke their original relations with William Penn. These references, however, are more consistent with the general idea of a treaty than the specifics of the Treaty tradition. In 1857, Granville John Penn donated to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania a belt of wampum (shell beads) depicting two men joining hands; the Lenapes had purportedly presented it to his great grandfather at the Treaty (it is now at the Philadelphia History Museum).

However, without a paper record issuing from the event itself, proponents of the tradition were unable to substantiate the location of the Treaty in Shackamaxon. Moreover, the traditional date, 1682, is unlikely because Penn’s crowded schedule in the months after his arrival is otherwise well documented. Nevertheless, in 1827 the Penn Society erected an obelisk where the Great Elm had once stood. Its inscription reads:

TREATY GROUND

of

WILLIAM PENN

and the

INDIAN NATIVES

1682

UNBROKEN FAITH

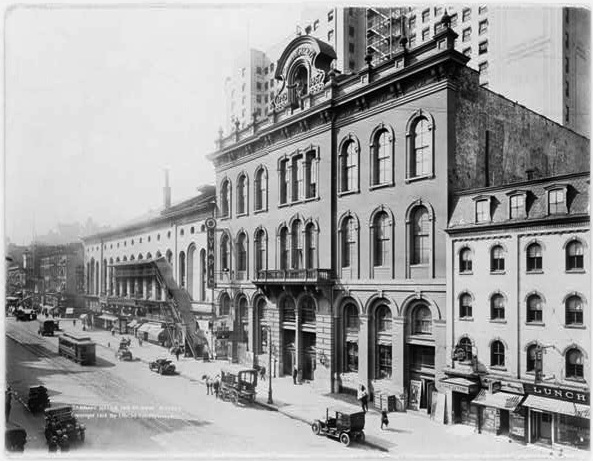

Considered Philadelphia’s first public monument, the obelisk has since been joined by other memorials in what is now Penn Treaty Park (1341 N. Delaware Avenue, in Fishtown).

Some academic commentators, especially critics of West’s painting, argue that the tradition was invented to idealize Pennsylvania’s past. Others suggest that it combines the memories of many documented treaties and land purchases, or that it aggrandizes a single such meeting into a Great Treaty. One possible basis is a treaty in June 1683 that resulted in several land deeds signed by Penn and the Lenape leader Tamanend (the legendary “Tammany”), among others. The location is unspecified, but it may have been Shackamaxon. Formal promises of friendship were likely exchanged, perhaps under the Great Elm. There is no evidence to the contrary.

Andrew Newman is Associate Professor and Graduate Program Director for the Department of English at Stony Brook University. He is the author of On Records: Delaware Indians, Colonists, and the Media of History and Memory (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2012). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Links

- Penn's Treaty with the Indians (Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts)

- Penn Treaty Museum

- As Long as the Creeks and Rivers Run: Traces of the Lenni Lenape-Part 1: Along the Delaware (PhillyHistory.org)

- Friends of Penn Treaty Park

- "W Penn's Treaty," Artifact of the Month (Philadelphia Archaeological Forum, March 2105)