Vagrancy

Essay

Vagrancy, generally defined as the act of continuous geographical movement by the poor, often has been interpreted to signify idleness, unemployment, and homelessness. Since the colonial era, it has been a driving social concern in the Mid-Atlantic region, where urban centers, including Philadelphia, attracted poor migrants seeking new economic prospects. Laws created to aid them as well as control their presence in the region were influential in shaping the legal culture of the United States.

From the colonial era to the twenty-first century, vagrants—individuals who could be convicted of the crime of vagrancy—have been labelled legally and colloquially as wanderers, vagabonds, beggars, tramps, and hobos. The term vagrancy described the status of individuals with no settled residence or long-term employment, but it also became a way of defining unsettled forms of poverty as crimes. As a concept, vagrancy became central to social thought regarding class distinctions in the United States throughout most of the nation’s history. The changing ways in which it was managed reflected larger shifts in American approaches to criminal justice, poverty, and migration.

Vagrancy laws adopted by colonists in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware, as in most other English colonies in America, derived from fifteenth-century English laws requiring all persons who did not own property to work. When transplanted to the colonies, these laws were used primarily to penalize movement by the lower classes. This was largely because vagrancy statutes often fell within poor laws, which were similar to later statutory welfare policies and governed subsistence aid to the poor.

Vague Statutes

From the eighteenth to the nineteenth centuries, vagrancy statutes were notoriously vague, and officials frequently used them to prosecute individuals considered to be intoxicated, disorderly, or sexually deviant. Justices of the peace, magistrates, and constables had authority to arrest or eject individuals who appeared to “have no visible means to maintain themselves,” who were “idle,” had “no legal residence,” or “followed no trade” so that destitute individuals would not add to the burden of publicly-funded poor relief. One harsh New Jersey statute passed in 1774 even stipulated that vagrants who returned to a district that ejected them would be punished with twenty lashes at the whipping post. This law remained on the books, if not in use, until at least 1838. Colonial Pennsylvania’s laws were less punitive, calling for the arrest and brief incarceration of beggars, individuals perceived by a justice of the peace to be nonresident destitute persons, and individuals considered to be vagabonds—generally open to the interpretation of justices.

Throughout colonial America, though many suffered from dire poverty, the number of vagrants was small. Wealth inequality in the colonies deepened in the eighteenth century, however, and the ranks of the poor grew dramatically in its last decades. Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York all had laws stipulating that indigent individuals who left their residence could be punished as vagrants or forced to return home.

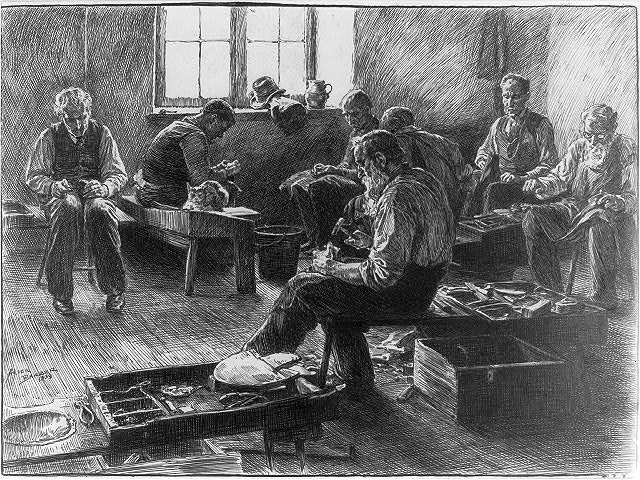

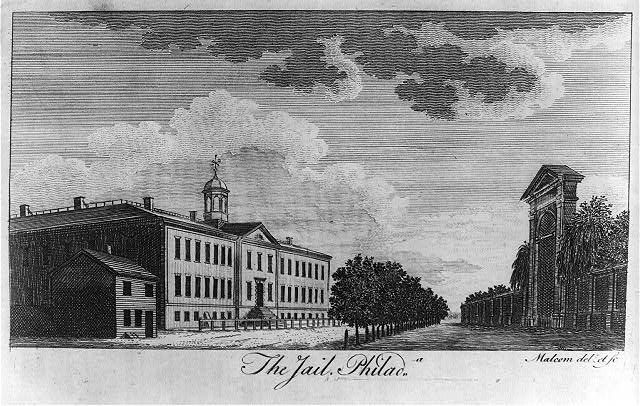

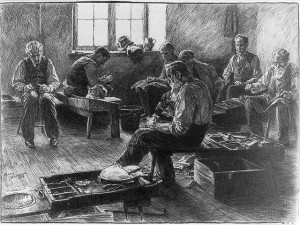

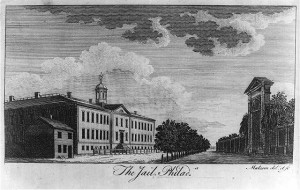

Philadelphia, which emerged as a leader in prison reform during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, also became noteworthy for its measures to manage its vagrant population. In 1790, Philadelphia revised its penal code in response to the swelling population of people living and begging in its streets and markets. The city rounded up the few hundred vagrants for imprisonment in the Walnut Street Jail. Many of these vagrants were runaway slaves and servants, unruly sailors, or prostitutes. Incarceration in regional jails or prisons, often at hard labor, for a term of one month became the general practice in Pennsylvania and most surrounding states. In Philadelphia, however, so little distinguished vagrancy from poverty that authorities often sent needier vagrants to the nearest almshouse, where they served their punishment and sometimes received some medical attention.

A Magnet for Vagrants

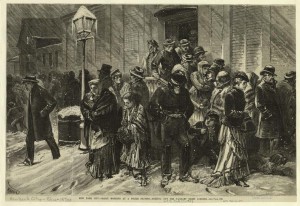

During the nineteenth century, Philadelphia’s central location, conveniently situated harbor, and economic connections to inland markets drew thousands of vagrants and pauper migrants who circulated among cities and smaller towns in Delaware, New Jersey, and New York. During the 1820s, nearly half of the vagrants at the Philadelphia Almshouse had traveled there from one of those three states. The severe economic depression that followed the Panic of 1819 caused vagrancy to increase dramatically. Philadelphia and New York City had the largest populations of vagrants in the nation. During the 1820s (and again later in the 1870s), one out of every 100 persons in Philadelphia had been convicted as a vagrant, while more still wandered in and out of the city without being apprehended. The “wandering poor” included whole families seeking work, many of them recent immigrants. When agricultural and maritime labor diminished for the winter, thousands flocked to Philadelphia looking for work and shelter to carry them through the season. These individuals became the most vulnerable to vagrancy convictions.

In Philadelphia in the 1820s and 1830s, indigent women and African Americans were disproportionately represented among those incarcerated for vagrancy, in higher numbers than other northern cities. In the 1820s, a time when the free Black community in Philadelphia was the largest in the nation, nearly half of the convicted vagrant population consisted of persons of color, although African Americans constituted less than one-tenth of the city’s population. This figure decreased dramatically as fugitive slave laws made geographical mobility significantly more dangerous for African Americans. The percentage of women in Philadelphia’s vagrant population in the antebellum era came close to matching their proportion of the population at large, a high rate that continued until the 1870s.

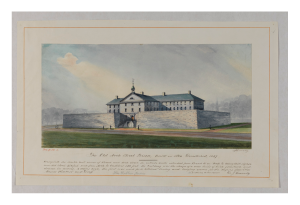

In keeping with the long-held view of vagrants as likely criminals, policing vagrancy became central to the evolution of the region’s criminal justice systems. During the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Philadelphia authorities used vagrancy statutes as expansive tools for removing disorderly or suspicious persons. The city’s Board of Prison Inspectors, as well as the influential philanthropic group known as the Philadelphia Prison Society, grew so concerned about the magnitude of poor vagrants in the early nineteenth century that they created a new penal facility, the Arch Street Prison, solely for incarcerating them. This facility, standing at Arch and Broad Streets, was among the first of its kind in the nation; later it also held debtors and untried prisoners, and it was the site of Philadelphia’s highest death toll during the cholera epidemic of 1832. Arch Street Prison, with its communal confinement and mingling of vagrants with debtors and those awaiting trial, stood as a counterpoint to Eastern State Penitentiary, just across the city, which served as a model for punishment reform and the benefits of separate confinement.

The Vagrancy-Corruption Link

In the nineteenth century, corruption in vagrancy prosecution was rampant. Vagrants often were released from incarceration before their sentences ended, only to be arrested again so that constables could earn additional prosecution fees. Race also persisted as a factor in prosecuting vagrancy. In Delaware, where vagrancy laws had long been used to compel individuals into labor contracts in other states, the legislature introduced new vagrancy laws in the 1840s that governed the employment and residence choices of African Americans and carried penalties of forced servitude. In antebellum New Jersey, part of the punishment for persons convicted of vagrancy involved justices of the peace forcibly binding the children of the accused into indentured servitude.

During economic depressions in the 1870s and 1890s, vagrancy again became pervasive in Philadelphia. During this period of the nation’s “tramp scare,” the swelling population of vagrants consisted almost entirely of white males, many of them desperate job seekers. In these decades, many vagrants voluntarily committed themselves to police lodgings or houses of correction as a way of securing shelter. The character of vagrancy remained the same during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Well into the twentieth century, unemployed migrants as well as the local homeless—two groups similar in their appearance as destitute and their need to use public spaces for personal needs, especially sleeping—were prosecuted as vagrants in Philadelphia. Into the 1950s, Philadelphia authorities used vagrancy laws to remove casual laborers and migrants from the city’s streets, in a process one legal scholar referred to as “banishment from the city of brotherly love.”

By the 1970s, vagrancy as a concept began to be eroded by challenges to the law from scholars, activists, social workers, and victims, largely on the grounds of its vagueness. The 1972 Supreme Court Case Papachristou vs. City of Jacksonville (405 U.S. 156, 1972) ruled that it was unconstitutional for governments to criminally prosecute individuals for conduct not clearly in violation of a law on the grounds that the vagueness of vagrancy statutes “encouraged arbitrary and erratic arrests and convictions.” This ruling effectively eliminated vagrancy as a criminal category. Prosecution of would-be vagrants then shifted toward arrests for activities such as panhandling and trespassing. Vagrancy as such was outmoded, but the individuals vulnerable to being destitute and unhoused remained, redistributed among the homeless population.

Kristin O’Brassill-Kulfan is a Ph.D. candidate in the School of History at the University of Leicester. She is writing a dissertation on the social history of indigent transiency in the early American republic. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University