Medicine Chest

Artifact

Drag across the screen to turn the object. Zoom to view details.

Read more below.

Essay

Medicine Chest, circa 1830. (Philadelphia History Museum Collection, Friends Historical Association Collection, 1987, Photograph by Sara Hawken)

This artifact serves as a witness to nineteenth-century medical practices. Resembling a large jewelry box, the domestic medicine chest opens on a hinge from the top to reveal twelve compartments of descending size. The compartments are filled with glass bottles sealed with glass stoppers. A drawer pulls out to reveal five more compartments for smaller containers and mixing tools. At the time of the chest’s use, the bottles would have been filled with various medicinal mixtures believed to mitigate, or in some cases, to cure physical suffering. Some of the bottled remedies may have included peppermint water, used to treat vomiting and diarrhea; lavender, used for digestive ailments and treating depression; and Epsom salts, which were used as laxatives and anti-inflammatory agents.

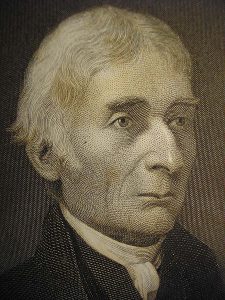

This medicine chest belonged to Stephen Grellet (1773-1855), a French-born Quaker who lived in the Philadelphia region for several years. The inside lid of the box is lined with a bluish-green fabric worn out from years of use. The chest’s portable nature is highlighted by the presence of a rectangular metal handle built into the top of the object. Scratches on the exterior wood finish attest to the object’s frequent use during the extraordinary lifetime of its owner.

During the middle decades of the nineteenth century, as residents of urban centers battled epidemics like the cholera outbreak that claimed 935 victims in Philadelphia in 1832, this type of medicine chest would have been a common possession in city homes. The boxes were sold by apothecaries, and demand increased with the summertime onslaughts of diseases that thrived in overcrowded and unsanitary living conditions. This intriguing example of one such personal medicine chest is part of the Friends Historical Collection at the Philadelphia Museum of History at the Atwater Kent.

Grellet was neither a physician nor a pharmacist but a Quaker missionary who ministered to his charges both spiritually and physically. Born Etienne de Grellet du Mabillier in Limoges, France, Grellet fled his motherland in 1793 to escape the violence of revolutionary France. After a brief sojourn in South America, he sailed north and took up residence on Long Island in 1795. While visiting the house of a local British Quaker and his French-speaking daughter, Grellet became acquainted with the writings of William Penn (1644-1718). Profoundly affected by a mystical experience that also occurred around this time, Grellet began to attend divine worship at the local Friends Meeting House. He dropped his noble French appellation and henceforth referred to himself simply as “Stephen Grellet.”

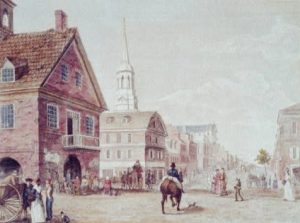

Toward the end of 1795 Grellet moved to the new nation’s capital city, Philadelphia. Now a confirmed Quaker, he regularly attended meetings at the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends. He embarked on a profession as an educator of the French language for the local population. Grellet’s first experience as a Quaker healer may have come in 1798 during an outbreak of yellow fever in Philadelphia. In his memoirs, Grellet wrote that during a trip to Cape May, New Jersey, he felt and intense calling by God to return to the city to minister to the sick. During such urban epidemics, it was more common for those who had sufficient resources to flee the cities to avoid illness. Grellet, however, at the age of 25, reentered the stricken city and visited the dwellings of many infected citizens. Although Philadelphia’s most devastating yellow fever epidemic had occurred in 1793, Grellet’s account of the 1798 oubreak paints a dismal scene of a desolate city inhabited mostly by the sick and dying, many of whom had been abandoned by family members and friends. Even nurses could not be readily obtained, leaving to non-professionals the burden of administering medicinal remedies and burying the deceased.

The medicine chest pictured above has been dated to circa 1830, indicating that Grellet would have used it later in his life and ministry. Alhough Grellet spent much of his adult life on missionary travels abroad, he spent most of 1830 at home with his family in Burlington, New Jersey, in a house built by Grellet’s father-in-law, the Revolutionary era printer Isaac Collins (1746-1817). In June 1831 Grellet departed on his fourth European missionary tour, which took him and possibly his medicine chest to England, the Rhineland, southern France, and Spain. Before returning home in July 1834, Grellet and his companions visited several hospitals, prisons and asylums in Europe, where they advised local and national magistrates on how to improve sanitary and social conditions in these institutions. In similar travels in the United States, Grellet he proclaimed the message of the Christian Gospel, attended and led Friends Meetings, and pleaded with local governments to provide humane environments for all human beings. Grellet, like most Quakers, was also a staunch advocate for the abolition of slavery.

Stephen Grellet’s medicine chest is a microcosm of a unique world on the verge of monumental change. The artifact holds poignant clues to mid-nineteenth century medical practice. As the century progressed, advances in medicine eventually lead to the understanding of germ theory and great improvements in medical practices and public sanitation. Humanitarian missions like those of Stephen Grellet led to improvements in hospital and prison care as well as the abolition of slavery. The well-traveled chest serves as a testimony to a little-known French connection between Philadelphia and the world.

Text by Christina Virok, an educator and graduate student in the History Department at Villanova University.