Our project reached an important milestone this week with the awarding of a two-year, $300,000 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. We are so grateful to the many organizations and individuals who have brought our project to this point: more than thirty partner organizations, more than 150 authors and editors, our digital publishing team and colleagues at our home base at Rutgers-Camden, and of course the users of the encyclopedia who attend our events, offer valuable suggestions, and use this resource every day. The NEH funds will support the next two-year period of accelerated content development, especially topics that span the Greater Philadelphia region. Check the site often and watch us grow!

Blog, page 7

National Endowment for the Humanities

Our Enhanced Digital Platform

Welcome to the newly enhanced Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia! As you explore our website, you will discover an array of new features and pathways for exploring our growing project. This enhanced digital platform builds upon suggestions from our users and partners, and it will allow us to continue to expand and take greater advantage of the capabilities of digital publishing. Take a look around!

Welcome to the newly enhanced Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia! As you explore our website, you will discover an array of new features and pathways for exploring our growing project. This enhanced digital platform builds upon suggestions from our users and partners, and it will allow us to continue to expand and take greater advantage of the capabilities of digital publishing. Take a look around!

Browse by geography. Explore topics through maps of sections of Philadelphia and counties in the region.

Browse by time period. Go to the timeline and link to any of our nine time periods. For each, you’ll find related topics as well as a more detailed timeline, an image gallery, topics on a map, links, and a related reading list.

Connect headlines and history. We have partnered with WHYY NewsWorks to make connections with the news through the Backgrounders feature on our home page and on individual topic pages.

Connect headlines and history. We have partnered with WHYY NewsWorks to make connections with the news through the Backgrounders feature on our home page and on individual topic pages.

Enhanced topic pages. We have improved our design and added links to additional digital resources so that each essay serves as a topical hub to resources throughout the region.

New theme pages. Our featured essays on themes such as “City of Brotherly Love” and “Workshop of the World” now have an enhanced presence on pages that also feature related topics, timelines, maps, and image galleries.

Author index. At a glance, this page displays biographical information about our authors and provides links to their essays.

Greater coverage. With the addition of timelines for themes and time periods, we provide a more comprehensive chronology of the region.

Greater accessibility. We have sharpened our typography to make the text more readable for individuals with low vision, and we have implemented other accessibility features.

More to come. Our site also enables browsing through artifacts, and we are working with the Philadelphia History Museum to add objects using virtual-reality photography. Also watch for additional maps and, of course, more topics as we continue to build The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. For all of this, we extend thanks for the participation of our users and partners and for the work of our digital publishing team. Implementation of the enhanced website, created in partnership with the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University, was made possible by a generous grant from the William Penn Foundation to the Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for the Humanities (the institutional home of the Encyclopedia). Concept designs, funded by a planning grant to the University of Pennsylvania Press by the Barra Foundation, were created by Brian T. Jacobs with input from participants in THATCamp Philly.

Whither the Downtown Department Store?

Readers who may have found David Sullivan’s essay on the history of department stores in Philadelphia of interest may well want to read a recent essay on the subject in Next City. With downtown booming, we might well expect to hold on to the one remaining standalone store, but even that prospect can not be assured.

Test Post

Test with a link.

New Civic Partner: Camden County Historical Society

We are pleased to extend the coalition of civic partners involved with The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia into South Jersey with the addition of the Camden County Historical Society. Watch for items from the CCHS collections to be featured in the image galleries that accompany topics of regional interest.

Anchors of Civic Life?

Shopping Centers Not All They Could Have been

The regional shopping mall is so much a part of modern American culture it is easy enough to forget how much more was expected of it with its introduction in the 1950s than simply being an “engine of commerce.” Taken together with David Sullivan’s entry on department stores, Matthew Smalarz’s essay on shopping centers suggests some of what has been lost in the geographic shift of retail activity over the past half century.

Regional shopping centers cropped up precisely at that point when the dispersion of metropolitan population introduced the phenomenon of suburban sprawl. The idealists behind the regional centers hoped their structures would help anchor new communities and give shape to ex-urban land use. As a writer for the Department Store Economist proclaimed in1954, “…no construction is more dynamic than the shopping center or as likely to influence a reform of the usual urban and suburban hodgepodge….A new generation of department store men and women…are showing the same high responsibility to the communities that their grandfathers showed when they helped to create the great downtowns which we know today in hundreds of cities.”

In their early days, suburban malls hosted fashion shows, opportunities for children’s play, high school proms, and even classical music concerts. If food courts lacked the grandeur of the tea rooms that female shoppers once gathered in downtown department stores, they nonetheless offered opportunities for sociability among women beyond the privacy of their homes, where so much of their attention was otherwise directed if they did not hold down fulltime jobs. For years the Cherry Hill Mall in New Jersey served as the gathering point for a number of former Camden residents whose dispersion outside the city in the 1950s and 1960s left them hungry for familiar faces and an opportunity to reminisce about their former lives.

Over time, these facilities became increasingly privatized, as community-oriented events aimed at generating a sense of loyalty to place as well as the crowds to animate them gave way to simply enticing paying customers. Shortly after her important book, A Consumer’s Republic appeared in 2003, I invited author and Harvard University professor Lizabeth Cohen to do a talk and sought to locate it in the courtyard of the Cherry Hill Mall, which received a good deal of attention in her book.The managers of the property said she could do so, but only after paying a $5,000 fee to gain access to the mall’s customers. As an alternative, they suggested the mall’s only bookstore, which we rejected after the manager failed to recognize the name of the publisher: Knopf.

The great irony of the commercial redevelopment of the Garden State Race Track nearby was the argument that it would fulfill Cherry Hill’s need for a town center. Apparently no one remembered, let alone imagined the mall once had been touted for serving just that function. As the site developed into an amalgam of different pods—for big box stores and clusters of housing—it served less of a model of “new urbanism” and more of an illustration of the basic problem critics point to in suburbs: physically induced social isolation.

The great irony of the commercial redevelopment of the Garden State Race Track nearby was the argument that it would fulfill Cherry Hill’s need for a town center. Apparently no one remembered, let alone imagined the mall once had been touted for serving just that function. As the site developed into an amalgam of different pods—for big box stores and clusters of housing—it served less of a model of “new urbanism” and more of an illustration of the basic problem critics point to in suburbs: physically induced social isolation.

Given the chance to create better communities on relatively open land in suburbs in place of urban centers that had evolved over time, developers fell well short of creating communities that integrated effectively the needs that enable thriving communities. We all have our favorite shopping destinations, but it’s hard to think of them today as the civic investments they were originally intended to be.

Putting the Delaware River Port Authority in Context

News that a grand jury is considering possible corruption in the award of economic development funds by the Delaware River Port Authority to politically connected recipients makes Peter Hendee Brown’s posting on the DRPA on this site especially timely. What the DRPA is supposed to do and how it operates is hard to grasp from the many news accounts that has put the agency in the news over time. Brown provides the background that helps make sense of the agency’s central importance to the region and the structural problems that arise from its operations.

When I first returned to the area after a long absence to write a book on Camden in the late 1990s, I was surprised at the way DRPA operated, not as an agent for regional development but as a cash cow that directed funds in equal portions to Pennsylvania and New Jersey without an overall strategic plan. Some projects made immediate sense, such as refitting the Philadelphia Navy Yard in the aftermath of the government’s departure from the site. Other investments were harder to sell. Spokesmen for the agency often talked about building tourism, for instance, by making investments on both sides of the Delaware River, and some good results came from that vision as well, not the least funds that helped make the President’s House memorial in Philadelphia a reality. But building tourism—which might conceivably generate returns by increasing tolls over bridges connecting the two states—was never central to DRPA’s goal. Supporting allies and garnering political credits appears to have topped the list of priorities, to say nothing of the financial benefits that might be gained through related contracts and political donations, among other things.

As Brown indicates, the creation of the DRPA was part of a movement to remove from politics certain public investments operating as non-partisan authorities. As Louise Dyble’s devastating critique of the Golden Gate Bridge and Highway District, Paying the Toll: Local Power, Regional Politics, and the Golden Gate Bridge, demonstrates, reigning in such authorities can be difficult indeed, and holding them accountable nearly impossible. DRPA may not reach that standard, but accountability remains a concern to the many people who continue to pay tolls into this organization’s coffers.

Whether an indictment will follow the grand jury’s investigation, DRPA deserves close scrutiny. We hope that our fellow citizens in the greater Philadelphia region will be aided in their assessment of the DRPA by Brown’s essay. Certainly, none of us have heard the last about controversies surrounding this important player in our region.

Defining Greater Philadelphia

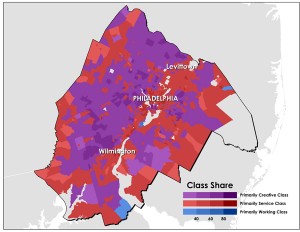

Richard Florida, well-known for introducing the term “creative class,” has recently released an assessment of the class divide distinguishing the Philadelphia area. Part of a larger series on U.S. cities, the report draws from the U.S. Census American Community Survey to designate areas across the region as part of one of three classes: creative, service, and working. The study is of particular interest to the editors of the encyclopedia because Florida provides one strategy for understanding the region just as we are about to undertake the challenge of assigning essays that will help us define what has constituted “greater Philadelphia” over time. We would be interested in how those who have been following our work react to Florida’s essay. It has already provoked a good deal of commentary on-line, and we welcome your own reactions.

Richard Florida, well-known for introducing the term “creative class,” has recently released an assessment of the class divide distinguishing the Philadelphia area. Part of a larger series on U.S. cities, the report draws from the U.S. Census American Community Survey to designate areas across the region as part of one of three classes: creative, service, and working. The study is of particular interest to the editors of the encyclopedia because Florida provides one strategy for understanding the region just as we are about to undertake the challenge of assigning essays that will help us define what has constituted “greater Philadelphia” over time. We would be interested in how those who have been following our work react to Florida’s essay. It has already provoked a good deal of commentary on-line, and we welcome your own reactions.

New Civic Partner:

Global Philadelphia Association

The mission of the Global Philadelphia Association is “to assist—and to encourage greater interaction among—the many organizations and people who are engaged in international activity in the Greater Philadelphia Region, to promote the development of an international consciousness within the region, and to enhance the region’s global profile.” We are pleased to have Global Philadelphia as a new civic partner, as well as to add The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia to the membership roll of Global Philadelphia. To find out more about Global Philadelphia, visit the association’s web site, and to learn more about Philadelphia’s global heritage, visit our “Philadelphia and the World” content theme.

Call for Volunteer Authors, Spring-Summer 2013

We are grateful to all of our volunteer authors and editors who are making The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia possible. Every day we receive hundreds of page views from information seekers, including teachers, students, and interested readers not just locally but also across the country and around the world. Our authors include the most prominent historians of Philadelphia as well as young scholars making their marks with new research and other subject experts.

For our next expansion, we seek volunteer authors to contribute essays related to the built and natural environment and regional events and traditions. We also seek volunteer authors to write about counties in the region, and some topics remain available to continue expansion of the themes of City of Neighborhoods, the Cradle of Liberty, and the Workshop of the World. For more information and to see a list of available topics, click here.