Anatomy and Anatomy Education

Essay

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, dissection and study of human corpses became the primary method for medical students to gain intimate visual and tactile knowledge of the body and prepare to perform surgery on the living. As the chief medical city in the United States during this period, Philadelphia also became the leading center of anatomical education.

Private and university-based anatomical courses in Philadelphia dated back to the 1750s. However, the scale of anatomical education took a great leap forward in 1762, when William Shippen Jr. (1736-1808), who had studied medicine in Edinburgh, began a public course of lectures on anatomy, which included human dissections. While any man could attend—women would not be allowed to study medicine until well into the nineteenth century—Shippen intended his course to serve as an introduction to a larger medical education geared toward those interested in a medical career. Within four years, Shippen joined another Philadelphia physician, John Morgan (1735-89), to found the Medical School of the College of Philadelphia (later the University of Pennsylvania).

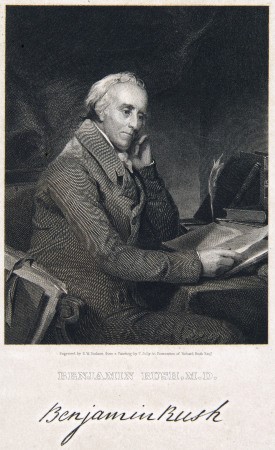

In spite of the first medical school emerging from Shippen’s anatomical lectures, the quality of anatomical education for the rest of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century was stymied by limited access to fresh corpses, partially the result of popular opposition to dissection. Public angst about dissection reached a boiling point in 1765 when a mob of sailors interrupted Shippen’s course and marched on his home. Philadelphians had suspected since his earliest lectures that Shippen had stolen bodies for dissection from a church graveyard, but he explained that he only dissected executed convicts and occasionally a body from the potter’s field, a public graveyard for the poor. Resistance also came from other physicians. Prominent physician Benjamin Rush (1746-1813) had little respect for anatomy as a standalone discipline and pushed his own physiological system for understanding human health. In Rush’s system, all diseases were caused by states of imbalance in the body, or as Rush put it “a disproportion between excitement and excitability.” Weather, emotional state, or diet, among other influences, caused these imbalances. Rush, a professor of chemistry at the Medical School of the College of Philadelphia from 1769 until his death in 1813, described anatomical study as just “a mass of dead matter. It is physiology which infuses life into it.” Rush rooted his theories in eighteenth-century approaches to medicine, and he significantly influenced medical education in Philadelphia throughout his life.

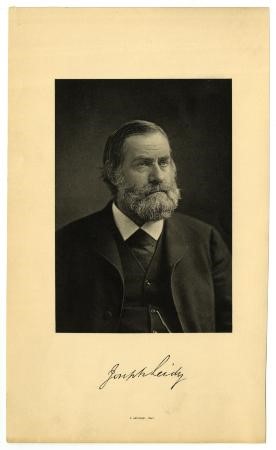

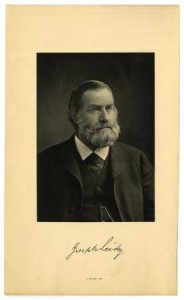

Following trends in Paris that emphasized pathological anatomy through postmortem dissections to understand disease, the generation of educators after Rush made anatomy the centerpiece of their educational system, which contributed to Philadelphia’s status as the focal point of American medical and scientific thought in the nineteenth century. During this era, with the University of Pennsylvania, Jefferson Medical College, the short-lived Pennsylvania Medical College, and three private supplemental anatomy schools, Philadelphia developed the most robust culture of anatomical education in the United States. Four Philadelphia anatomy professors—Caspar Wistar (1761-1818) of the University of Pennsylvania; William Horner (1793-1853), who succeeded Wistar at the University of Pennsylvania; Horner’s successor Joseph Leidy (1823-91); and Samuel G. Morton (1799-1851) at the Pennsylvania Medical College–wrote anatomy textbooks. Leidy even had his personal copy of his textbook bound in human skin.

One of the major differences between eighteenth- and nineteenth-century anatomical education in Philadelphia and elsewhere was an increasing focus in the nineteenth century on pathological anatomy, popularized by doctors in France. Pathological anatomists used post-mortem dissections for the purpose of discovering the cause of death and how specific diseases affected the tissues and organs of the body. While physicians had been making post-mortem dissections for centuries, practitioners in the Paris clinics dissected thousands of cadavers and argued that disease could be observed as lesions in the tissue, as opposed to previous theories that considered specific organs as the seats of disease.

During this period, medical schools began to assemble significant anatomy collections in museums featuring objects like diseased organs, human skulls, and animal skeletons. The University of Pennsylvania’s anatomical museum (first assembled by Caspar Wistar from 1808 to 1818 and later part of the Wistar Institute) and the College of Physicians and Surgeons’ Mütter Museum (founded in 1858) represented two of the largest American anatomy museums in the nineteenth century. Many professors also incorporated artifacts from these collections into their classes. Utilizing museum collections and their professors’ lectures, students in Philadelphia learned about comparative anatomy between animals and humans, along with the supposed differential anatomy of the human races. At the University of Pennsylvania, Leidy even told his students that Black and white people were different species. As a result, in addition to its value as a medical subject, the study of anatomy carried social and political implications.

Because Philadelphia housed so many venues for dissection in the nineteenth century, anatomy professors competed for fresh corpses. Anatomists fashioned a secret arrangement with the city government, which gave them open access to potter’s fields. This arrangement yielded approximately 450 corpses per year, but Philadelphia physicians sometimes still had to ship in bodies from New York City. In 1828, Philadelphia anatomists signed a contract to ensure that each professor received a fair portion of available anatomical material, which helped alleviate tension between anatomy teachers.

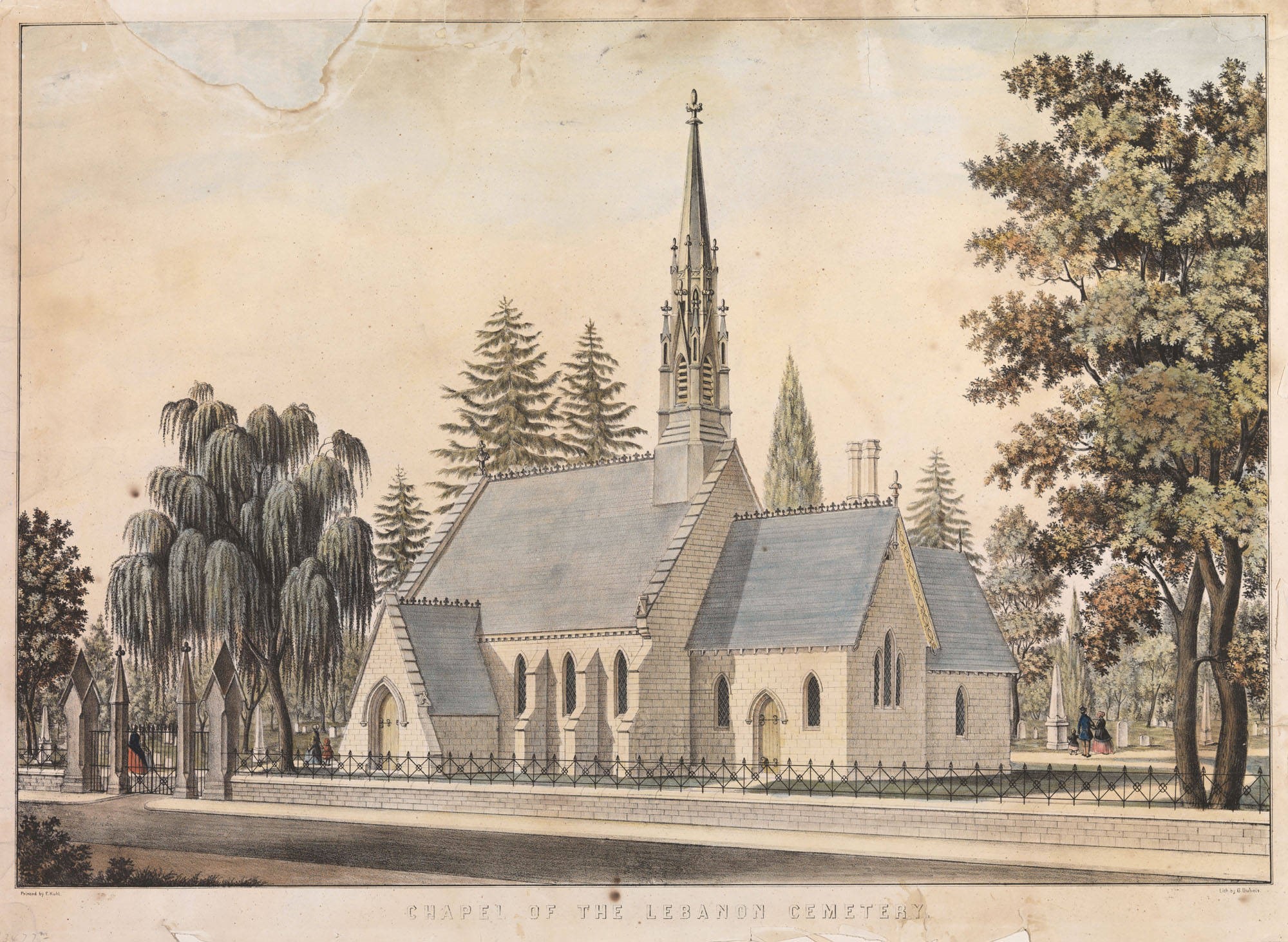

The city’s most public body-snatching scandal took place in 1882, after gross anatomy had lost its central position in medical pedagogy. In 1882, Jefferson University Professor of Anatomy William Smith Forbes (1831-1905) was publicly tried on charges of stealing six cadavers for his anatomy course from the historically African American Lebanon Cemetery. While Forbes was eventually acquitted, the case revealed a previously little-known Black market in corpses that went back to the beginning of the century. In spite of scandals like the Forbes case, students continued to view dissection as a right of passage. Into the twentieth century, they persisted in a ritual of posing for photographs with cadavers, a practice that underscored the continued influence of anatomy and dead bodies on medical students and their relationship to patients and death.

The study of anatomy and Philadelphia’s role in it rose to the peak of their importance within American medicine in the antebellum era. Even after the rise of German laboratory medicine and the ascendance of germ theory in the 1870s and 1880s made gross anatomy just one subject among many in the medical curriculum, Philadelphia physicians continued to make breakthroughs in histology (microscopic anatomy) and later neurosurgery. Leidy, whose tenure at the University of Pennsylvania lasted from 1853 until his death in 1891, utilized microscopic anatomy in his lectures and for his 1861 textbook. Pathological anatomy continued to be a fruitful area of medical exploration into the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Although gross anatomy remained important for medical students to learn the structures of the human body through anatomical education, it never again occupied the central theoretical position in medicine as it had in the first half of the nineteenth century.

While gross anatomy fell into the background of American medical education, professors at Philadelphia universities continued to make names for themselves in anatomy-related branches of inquiry, including neuroanatomy and neurosurgery. At the turn of the twentieth century, the University of Pennsylvania emerged as one of the country’s leading centers for neuroscience. Charles Harrison Frazier (1870-1936) led a cohort of neurosurgeons in Philadelphia who contributed to the creation of the Departments of Neurosurgery at the University of Pennsylvania and Temple University. Frazier and William Gibson Spiller (1863-1940) pioneered a new surgical method for treating trigeminal neuralgia and made additional breakthroughs in treating pain in the nervous system. Together these neurosurgeons shaped the future of neuroanatomy and trained the next cohort of the country’s leading neurosurgeons, including Francis Grant (1891-1967) and Robert Groff (1903-75). Through the neurosciences, Philadelphia continued to maintain a prominent position in the American medical profession, and anatomy continued to occupy a central role in the production of medical knowledge.

Christopher Willoughby is a Ph.D. candidate in the History Department at Tulane University in New Orleans, where in 2012 he also received his master’s. He is completing his dissertation entitled “Pedagogies of the Black Body: Race and Medical Education in the Antebellum United States,” which has been supported by grants from the National Science Foundation and the Consortium for the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine (Philadelphia). He was the 2014 winner of the W. Curtis Worthington Jr. Prize from the Medical University of South Carolina’s Waring Historical Library, for the best graduate student essay in the history of health science. (Author information current at time of publication.)

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Number 1353086. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University