Atlantic City, New Jersey

By Bryant Simon

Essay

Before Disneyland, Atlantic City was the first great middle-class resort in the nation, especially the Philadelphia region. From its founding in the 1850s through the early decades of the twenty-first century, Atlantic City succeeded and failed based on its ability to make itself in the image of the American middle class. As the cultural tastes and social attitudes of the shop owners, professionals, and small-business people who visited the area changed, the city changed in response with lasting effects to its vitality and viability.

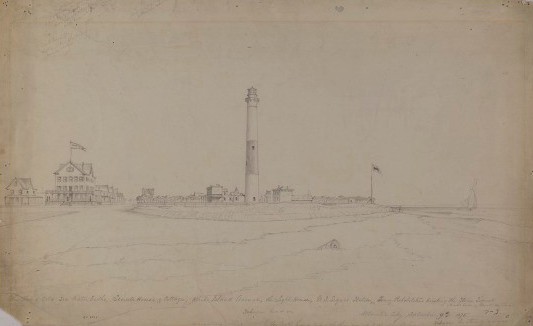

Geography brought Atlantic City into existence. Throughout the first half of the nineteenth century beach resorts like Cape May, New Jersey, and Newport, Rhode Island, steadily grew, catering to the affluent. Looking to capitalize on the emerging and profitable tourist trade, in 1854 a pair of Philadelphia developers pulled out a map and drew a straight line between the city and the shore. They landed sixty-two miles away on a spot on the northern end of Absecon Island, which became Atlantic City. When they actually got there, they didn’t find much beyond a handful of families and a thicket of briars and bushes. Within a few years, the land was cleared and a hotel and several dozen houses were built. The most important of the early buildings, the railroad station, became the city’s financial pipeline. Center City accountants and West Philadelphia merchants now had an affordable option to get to the ocean. While it cost more than a subway, the trip to Atlantic City remained within the reach of a growing middle-class, which made enough to pay for the railroad ticket and a few nights or a week in a hotel or rooming house near the sea. So while Atlantic City was not like toney Cape May, it was not like working-class Coney Island either.

What that first generation of Philadelphia visitors wanted was a break from the city. Through the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, middle-class Americans worried about the ill effects of the nation’s teeming cities. They feared that these rapidly growing, unregulated places compromised their health. The shore promised restoration. In the 1890s, several Philadelphians, paid by Atlantic City hotel owners, claimed in a newspaper advertisement that Atlantic City possessed “three of the greatest health giving elements known to science – sunshine, ozone, and recreation.” Eager to get that healthy break from noxious urban fumes, city residents boarded trains to the shore in droves.

A Boardwalk Debut

In 1870, an Atlantic City hotel owner and a railroad conductor got an idea to let health-seekers get near the water, without getting sand everywhere. They laid wood planks over the beach for people to walk on. Eight feet wide and a mile long, the boardwalk became an instant hit. When a storm wiped it away, city leaders built a second, third, and then fourth walkway. None of these lasted. On the fifth try, in 1896, engineers used steel and concrete reinforcements to construct a taller, more weather-resilient structure. Wider in places than a two-lane highway, the new, durable five-mile strip emerged as the city’s signature attraction. The city’s Chamber of Commerce eventually promoted it as “the eighth wonder of world,” the only Boardwalk anywhere that deserved to be spelled with a capital B.

The horizontal Boardwalk transformed Atlantic City from a health resort into an urban showplace, a dense and vertical fantasyland of affordable luxury and leisure. From 1920 to 1960, Atlantic City became known as the “Nation’s Playground,” and it attracted more visitors each year than the combined populations of New York City and Philadelphia. These crowds came for their health, but even more, to see and be seen. During summer days, they frolicked in the sun and surf and bronzed their bodies. On summer nights, these women and men dressed up in minks and sports jackets, jamming the Boardwalk and giving the promenade the feel of Broadway on Saturday night. In the off-season, thousands of neat and respectable teachers, Legionnaires, and electricians poured into the city’s massive Boardwalk Convention Center.

As the crowds multiplied, the city expanded. Amusement piers, like Steel Pier with its theaters and showrooms, jetted out into the ocean as far as the eye could see. Towering over the Boardwalk and its row of pricy jewelry stores and ornate movie houses rose a string of massive and lavish hotels, like the Marlboro Blenheim, the Ritz, and the Chalfonte Hadden Hall. Behind the hotels were nightclubs and restaurants that had the smoky and swank feel of a Frank Sinatra song. (Not surprisingly the North Jersey singer regularly appeared in town.) Farther back, the city resembled parts of Philadelphia, with its block after block of narrow streets lined with tidy row houses. At the corners, there were delis and taverns. On the bigger streets, like Atlantic and Pacific Avenues, there were churches, municipal buildings, stationery stores, and law offices. As in Philadelphia, Atlantic City’s residential spaces resembled, in some ways, the Balkans: Italians lived in Ducktown, Jews in the Inlet and Chelsea, African Americans on the Northside. The African American community was particularly significant. By 1930, Atlantic City reached its all-time population peak of 66,000 residents and African Americans, mostly migrants from the South, made up a quarter of city residents, the largest proportion of any New Jersey city at the time.

Convention Destination

Over the first half of the twentieth century, as Atlantic City grew, fueled by mass tourism, it became an iconic and famous place of firsts. It was one the nation’s first convention destinations. Atlantic City locals also invented the Miss America Pageant and salt-water taffy. Jerry Lewis (b. 1926) and Dean Martin (1917-95) first got together in the city’s clubs, and Frank Sinatra (1915-98) and Sammy Davis Jr. (1925-90) honed their acts before heading to Las Vegas. The country’s most dynamic labor organization, the Congress of Industrial Organizations, formed there in 1935, and feminists announced their arrival on the national scene in 1968, trying to burn bras and beauty products in protest against swimsuit contests and bouffant hairdos. And it was from Atlantic City’s streets named after the United States and the world’s oceans that the most popular board game of all time, Monopoly, took its property names.

Throughout its heyday, Atlantic City remained segregated. Blacks could not check into Boardwalk hotels, sit where they wanted in the city’s movie houses, sunbathe where they chose, or buy a home in any neighborhood. Yet African Americans played important, but tightly cast, roles in the city’s tourism industry. Steel Pier featured minstrel shows, hotels employed uniformed butlers, and rolling-chair operators hired black men to push well-dressed white men and women down the flat surface of the Boardwalk. Later at night, some of these couples ventured over to Kentucky Avenue, on the black side of the city’s racial divide, to catch a bawdy dance show or listen to a hot jazz band. White Philadelphians and others put on their best clothes and came to town to show off that they had made it in America and that they had become people of leisure. But just like back home, they wanted, it seemed, the maintenance of segregation. “Good” neighborhoods, like good restaurants and clubs, were white ones. Yet in Atlantic City there was an added twist to the pattern of American race relations. Middle-class whites who typically cooked their own meals, walked to work on their own, and cleaned their own living rooms could hire African Americans, just like rich people did all the time. They could show off and quietly boast that they were better than someone else, in this case African Americans. The ability to do that made Atlantic City for years an appealing and important place.

If white middle-class ideas about race had been crucial to Atlantic City’s success, changes in the national racial narrative in the wake of the Brown v. Board of Education decision, snarling dogs on the front pages of papers, and stirring protests broadcast on television posed a challenge to the resort town and what it had to offer. Whites might not have given up on the privileges of whiteness when it come jobs and real estate red lining, but they no longer wanted the Gone With The Wind or Amos and Andy performances of the past, like the minstrel shows and rolling-chair rides. With the advent of cheap air travel and a growing predilection for the comforts they associated with newly preferred suburban homes, they fled recently integrated urban amusement parks for expensive fun places, like Great Adventure in Jackson, New Jersey, and Disneyland in California, which kept out the poor and the carless by keeping ticket prices high and setting up in ex-urban locations.

Declining Population

City residents in Atlantic City fled as well, as laws and customs changed and African Americans moved out of the city’s segregated enclaves into former all-white neighborhoods. Desegregation occurred just as Atlantic City began to experience telltale signs of crisis, similar to many other American cities. Work disappeared. Drug use spread and crime spiked. Atlantic City became a place to avoid. By 1960, its population dropped below 50,000, and it continued to fall in every census for the next forty years. The summer crowds stayed away as well. One local joked in the early 1970s that you could roll a bowling ball down the Boardwalk and not hit a single person.

As Atlantic City lost its base of white tourists and white residents, city leaders tried to figure out how to lure the middle-class crowds back to town. They talked about expanding the convention center and building new amusements parks and maybe an aquarium. One local man suggested turning the city dump into a ski slope. But most politicians, hotel owners, and restaurateurs could not take their eyes off the neon lights of Las Vegas, then the only place in the United States where people could legally play blackjack and slot machines. If they could bring casinos to Atlantic City, the boosters bet, people would come from all over to gamble, see shows, and shop. Opponents worried that gaming would corrupt the weak and embolden East Coast mobsters. Aided by last-minute sermons from Methodist ministers, the first statewide referendum to allow for casinos in Atlantic City failed in 1974. Gambling proponents got another chance two years later. This time they were better-organized and -funded and touted a better message. Politicians still talked about saving Atlantic City, and that is why they agreed to a monopoly on casinos for the city, but they also promised to use a portion of gambling revenues to help the state’s elderly with their bills. This time the campaign worked. Its success, at the same time, reflected a growing acceptance in middle class circles for gambling, in the form of lotteries and then casinos, as a better way to raise revenues than property and business taxes.

When news spread that the statewide referendum authorizing gambling in Atlantic City passed on its second try in 1976, locals danced on the Boardwalk. They imagined the city once again packed with well-dressed, free-spending visitors. At the same time, they imagined workers with steady paychecks from the casinos filling the houses and streets of the city. They thought the shops and movies houses would come to Atlantic Avenue and beyond. Politicians fueled the fervor, describing the casinos as a “unique tool of urban renewal.”

1978: The Casino Parade Begins

On May 26, 1978, Resorts International Casino threw open its doors to a throng of eager gamblers. People waited in line for up to five hours for seats at the tables and slot machines. During its first seven months in operation, the new casino earned a whopping $134 million. In the ensuing years through 2014, Resorts and all the casinos that came after it along the Boardwalk and the bay on the north side of town took in more than $60 billion in earnings. At their height in 2005, the casinos employed more than 50,000 people and provided two-thirds of the city’s total tax revenues. As a result of the casino boom, Atlantic City became once again one of the most popular resorts in America–only Las Vegas and Disney World attracted more visitors each year in the 1990s. However, the average visitor to Atlantic City stayed less than six hours, just enough gamble and get going.

All these people and all this money did not save Atlantic City. With the encouragement of the state government, eager to add jobs in the building trades, the casino owners tore down the showy palaces of the past and replaced them with slender, non-distinct boxes, adorned with only neon lights and over-sized parking decks. They pulled in customers with offers of free food, drink, and entertainment, and only let them escape, it seemed, when they had no money left to spend. This left little to trickle down to the city surrounding the self-contained gambling towers. As a place to live and work, Atlantic City suffered what turned out to be a cruel and unanticipated fate.

Ten years after Resorts first opened its doors, Atlantic City had a dozen massive casinos, but it had lost 20 percent of its population and housing stock. While it once had fifteen movie houses, by 1988 it did not have a single movie theater in operation. It didn’t have a supermarket either. During those same ten years, four hundred businesses, including 250 restaurants, closed. Atlantic Avenue—the city’s Main Street—turned into a dingy collection of greasy spoons, cash-for-gold outlets, and empty storefronts. Crime rose and so did unemployment, despite all of the casino jobs, along with rates of infant mortality, homelessness, and heroin use. When pollsters asked city residents in 1985 if they would vote for gambling again if given a second chance, the majority said No. The next year, Money magazine voted Atlantic City the worst place to live in America.

A $2 Billion Casino

With the turn of the twenty-first century, conditions started to improve somewhat in Atlantic City. Population in the city stabilized, higher-end housing units went up in a few areas, and banks lent millions to developers to build new hotels, shopping piers, and high-end restaurants. In 2012, the two-billion-dollar Revel Casino opened, symbolizing to some the city’s rebound. Still Atlantic City remained a city without a full-scale supermarket or a department store.

Between 2008 and 2015, Atlantic City’s recovery stalled and its casino-led economy sputtered. The roiling impact of the Great Recession as well as declining interest in gambling among the middle-class millennial population cut the casino crowds. Super Storm Sandy in 2012 further disrupted business. But the chance for Atlantic City’s recovery was made even harder by the fierce competition it faced as lawmakers in Pennsylvania, Maryland, New York, and Delaware authorized casino and online gambling in their states, hoping to capture new sources of revenue without raising taxes. In 2014, four Atlantic City casinos, including the shiny and new Revel, closed their doors. The shutdowns cost the community thousands of jobs and rocked its confidence.

Atlantic City civic leaders once again, found themselves having to reimagine the city. Could it make a return as a gambling mecca? If so, what could it offer that its new nearby rivals did not have? Could it rebuild itself as center for education and medicine? Could it become again a major convention center, even as it lost thousands of essential hotel rooms? Would middle-class Philadelphians move in for the summer months, attracted by cheaper real estate opportunities than other shore towns? The only thing certain is that there will be winners and losers, and that Atlantic City’s fate as a beach resort and year-around community will reflect the political winds, social forces, and cultural styles in Philadelphia and the world beyond.

Bryant Simon is Professor of History at Temple University and the author of Everything But the Coffee: Learning about America from Starbucks (2008), Boardwalk of Dreams: Atlantic City and the Fate of Urban America (2004), and co-editor of Jumpin’ Jim Crow’: Southern Politics from Civil War to Civil Rights (2000). His work on Atlantic City has won awards from the Organization of American Historians, the Urban History Association, and the New Jersey Historical Commission. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Atlantic City's New Barometer (WHYY, April 11, 2012)

- Capturing the Changeable Atlantic Ocean in Painting and Sculpture (WHYY, January 2, 2015)

- Casino Tax Plan for Atlantic City Due for Vote Early This Month (WHYY, January 4, 2016)

- Atlantic City Rescue Plan Heads to Christie's Desk (WHYY, January 8, 2016)

- Tax Credits Approved for Stockton Atlantic City Campus (WHYY, January 12, 2016)

- Sweeney Pushing for NJ Takeover of Atlantic City (WHYY, January 12, 2016)

- Atlantic City takeover proposal rattles local leaders (WHYY, January 14, 2016)

- Casino planned at reopened Revel (WHYY, January 19, 2016)

- Atlantic City will put Bader Field up for auction (WHYY, March 17, 2016)

- Running out of cash, Atlantic City to close government for three weeks (WHYY, March 22, 2016)

- Does the Atlantic City takeover proposal pass legal muster? (WHYY, March 29, 2016)

- A compromise on Atlantic City could be in the works (WHYY, April 15, 2016)

- Atlantic City holds open tryouts for new lifeguards (WHYY, June 14, 2016)

- Atlantic City's Trump Taj Mahal casino plans to shut down on Oct. 10. (WHYY, August 6, 2016)

- Atlantic City casino revenue down 4.9 percent in August (WHYY, September 14, 2016)

- Atlantic City: We can pay state loan back and still keep our water utility (WHYY, September 26, 2016)

- Atlantic City releases a five-year plan to avoid bankruptcy (WHYY, October 25, 2016)

- After N.J. rejects Atlantic City’s recovery plan, city officials push back (WHYY, November 2, 2016)

- Icahn surrendering Trump Taj Mahal casino license (WHYY, January 3, 2017)

- What’s happened since New Jersey took over Atlantic City in November? (WHYY, March 27, 2017)

- Two new casinos open early in Atlantic City (Associated Press via WHYY, June 25, 2018)

- Atlantic City is one of the most flood-vulnerable coastal cities, report finds (WHYY, March 11, 2024)