Automobile Racing

Essay

Motorsports developed into a popular leisure activity in the Philadelphia area during the twentieth century. Originally an activity enjoyed by wealthy car owners, the advent of the Model T Ford allowed local technophiles to build their own race cars and compete in regional races. By mid-century, drivers raced at fairground horse tracks and purpose-built speedways throughout the region. Although several Philadelphia-area speedways closed by the late twentieth century because of increased safety concerns and suburbanization, auto racing continued in eastern Pennsylvania, Southern New Jersey, and Northern Delaware.

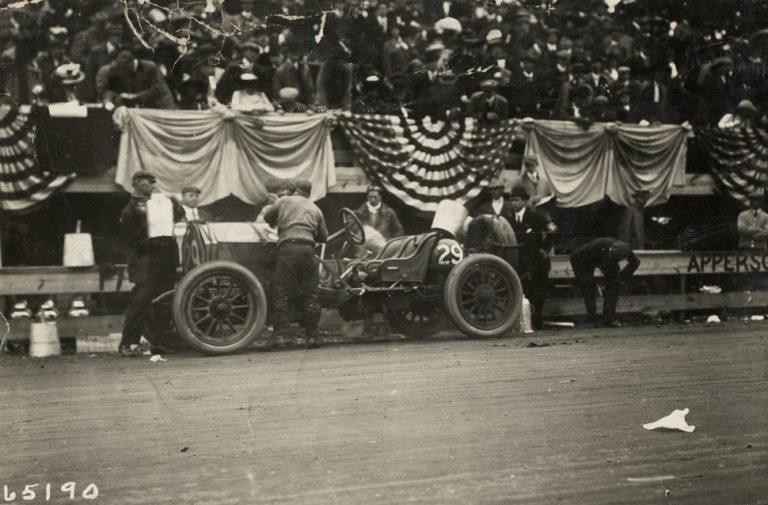

Automobile racing originated in Europe as automobile manufacturers worked to test their car designs and market them to consumers. Wealthy Philadelphians formed the Quaker City Motor Club, which introduced automobile racing to area residents in 1906 at Point Breeze Racetrack, a horse track in South Philadelphia. This race also marked Pennsylvania’s first automobile racing fatality when Ernest D. Keeler (ca.1879-1906) crashed during practice for the event.

The Quaker City Motor Club also sponsored automobile endurance races on area roads. From 1908-11, the club organized a 200-mile race on an eight-mile course through Fairmount Park for American-manufactured automobiles with stock chasses. The event attracted local drivers such as brewer Erwin Bergdoll (1890-1965) as well as nationally-known racers including George Robertson (1884-1955) and Louis Chevrolet (1878-1941). City leaders debated the benefits of these races, and the Fairmount Park Commission suspended all racing in 1912 after concluding that motor races endangered participants and encouraged recklessness among the city’s automobilists.

Philadelphia-based interest in auto racing expanded in 1919, when a group of local businessmen founded the National Motor Racing Association. They promoted automobile races in Byberry, Pottstown, and West Chester, Pennsylvania, as well as Harrington, Delaware. The National Motor Racing Association and other regional promoters held automobile races on horse tracks during annual agricultural expositions at area fairgrounds.

In 1926, the National Motor Racing Association constructed one of the nation’s first purpose-built dirt speedways in Langhorne, Pennsylvania. Nicknamed “the big left turn,” the mile-long Langhorne Speedway featured a unique circular design, which allowed drivers to reach higher speeds. Area residents drove their family automobiles to the track located along Route 1 between Philadelphia and Trenton to see the nation’s leading drivers race against local favorites.

Drivers from Greater Philadelphia garnered national acclaim for their racing exploits during the interwar period. In 1928, Charles Raymond “Ray” Keech (1900-29) of Coatesville set a new land speed record of 207 mph at Daytona Beach, Florida. Keech recorded several wins on local dirt tracks and won the 1929 Indianapolis 500 in a car entered by Philadelphian Maude Yagle (1885-1968). The only female car owner to ever win the Indianapolis 500, Yagle continued to hire Philadelphians, including Fred Winnai (1905-77), Jimmy Gleason (1898-1931) and Frank Farmer (1892-1932), to drive her race car over the next few racing seasons.

With the advent of smaller and less powerful race cars known as “midgets” during the Great Depression, automobile racing resumed within Philadelphia city limits. Promoters hosted midget races at Yellow Jacket Stadium in Northeast Philadelphia at Frankford Avenue and Deveroux Street. Formerly home to the National Football League’s Frankford Yellow Jackets, the stadium had been converted into a paved, one-fifth-mile speedway. Yellow Jacket Stadium held night races each week prior to World War II and remained popular with local residents who could walk or take public transportation to this speedway in the city.

The Office of Defense Transportation suspended all motorsports across the United States in 1942 in an effort to conserve the nation’s limited supplies of gasoline and rubber. Racing resumed immediately following the Allied victory. Postwar interest in automobile racing remained high, and a second Yellow Jacket Speedway located at Erie Avenue and G Street hosted biweekly midget racing programs from 1945 to 1950.

Over the next four decades, drivers competed in American Automobile Association (AAA)-sanctioned events, NASCAR (the National Association for Stock Car Racing), and in racing motorcycles and USAC (United States Auto Club) sprint cars at area speedways. Langhorne Speedway continued to attract the nation’s top open-wheel drivers, including A.J. Foyt (b. 1935), Mario Andretti (b. 1940), Al Unser (b. 1939), as well as NASCAR stars such as Lee Petty (1914-2000), Tim Flock (1924-98), and Edward “Fireball” Roberts (1929-64). Concerns over drivers’ safety as well as development along Route 1 led to the closure of Langhorne Speedway in 1971. Dirt track racing continued at local fairgrounds, including Harrington, Delaware and Flemington, New Jersey, until the 1990s.

The rising national popularity of stock car racing encouraged the construction of two area asphalt speedways for NASCAR racing events. The one-mile Dover International Speedway (originally called Dover Downs Speedway) located in Dover, Delaware, opened in 1969. Pocono Raceway, known as the “Tricky Triangle” because of its three sharp turns, began hosting races on its 2.5 mile speedway in 1971. Among the largest sports venues in the mid-Atlantic, Pocono Raceway and Dover International Speedway are known as “superspeedways.” Each track hosts two NASCAR Sprint Cup Series races each racing season. Large crowds of race fans camp on-site in order to attend qualifying races, related events, and socialize throughout the weekend of the race.

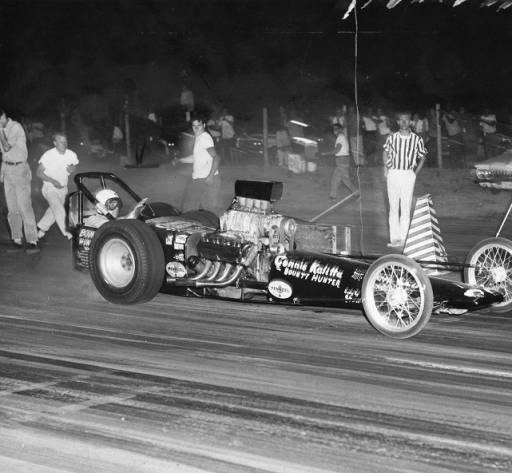

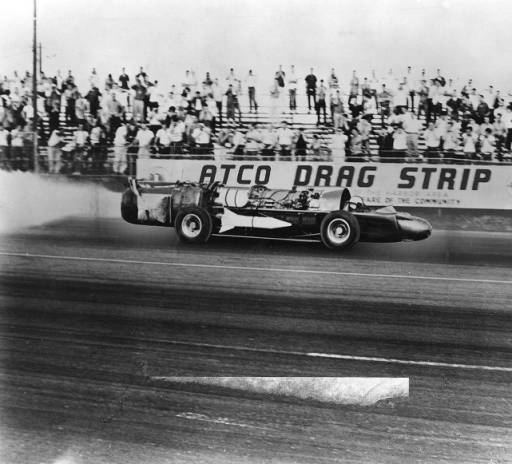

In the first decades of the twenty-first century, racetracks throughout central Pennsylvania, such as Williams Grove, Lincoln, and Port Royal Speedways, as well as New Jersey’s Atco Dragway, New Egypt Speedway, and Bridgeport Speedway, hosted a variety of racing programs each season. NASCAR racing also continued annually at Pocono Raceway and Dover International Speedway.

Shared interests in speed, automobiles, and technological daring brought people from diverse backgrounds together at the region’s speedways, and automobile racing remained a popular leisure activity for mid-Atlantic residents. Motorsports, especially NASCAR events, continued to provide significant income to area tourism.

Alison Kreitzer is a Ph.D. candidate in the History of American Civilization at the University of Delaware. She is writing a dissertation about dirt track automobile racing in the mid-Atlantic region. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Local race car museum finishes first worldwide (WHYY, November 17, 2011)

- Beautiful weather for NASCAR in Delaware (WHYY, June 4, 2012)

- NASCAR overhaul could spark interest at Delaware track (WHYY, January 30, 2014)

- NASCAR returns to safer Delaware track (WHYY, May 10, 2016)

- Blazing a trail for African-American racers (WHYY, June 22, 2018)

Links

- Langhorne Speedway Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- National Association for Stock Car Auto Racing (NASCAR)

- Indianapolis Motor Speedway

- Dover International Speedway

- Pocono Raceway

- Williams Grove Speedway

- Lincoln Speedway

- Port Royal Speedway

- Atco Dragway

- New Egypt Speedway

- Bridgeport Speedway