Better Philadelphia Exhibition (1947)

By Stephen Nepa

Essay

The Better Philadelphia Exhibition, which ran from September 8 to October 15, 1947, at Gimbels department store in Center City, showcased new ideas for revitalizing Philadelphia after decades of depression and war. Conceived by young architects and planners and funded by prominent citizens, the exhibition introduced more than 350,000 people in the metropolitan area, free of charge, to a vision of the city of the future.

By 1945, American cities suffered from neglect, aging infrastructure, and overcrowding. Yet victory in World War II fostered a sense that cities could be improved with new spaces for living, working, and recreation. Urban redevelopment programs introduced by national housing acts in 1949 and 1954 remade the landscapes of cities such as New York, Boston, and New Haven, Connecticut. In many cases, redevelopment relied on clearing slums and other blighted structures to make way for parks, commercial structures, and expressways as well as new apartment blocks. While Greater Philadelphia adhered to certain aspects of a clearance approach to renewal, the organizers of the Better Philadelphia Exhibition also incorporated historic preservation, concern for pedestrians, and the use of existing structures to complement new projects.

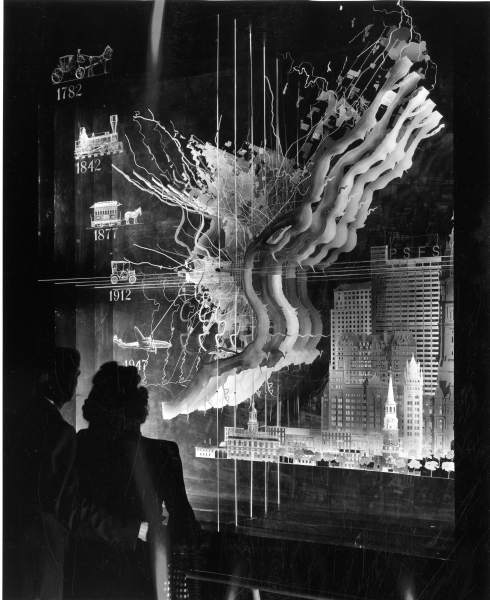

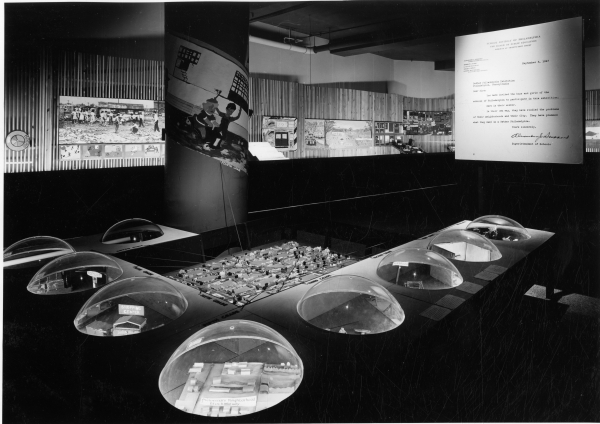

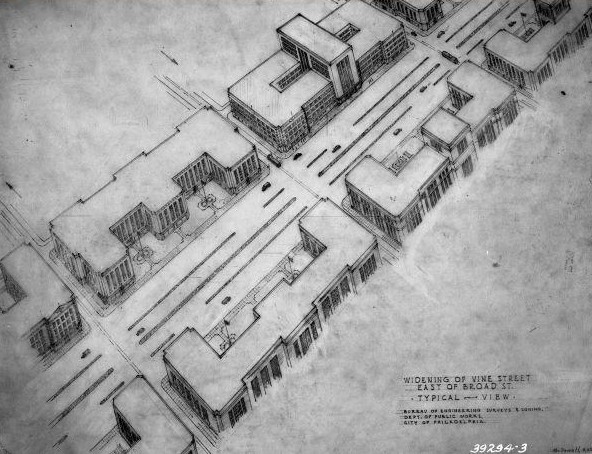

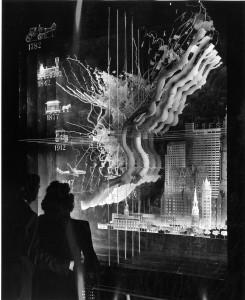

Along with sculpture, light shows, information about the urban planning profession, and a history of the city’s growth, an elaborate thirty-by-fourteen-foot diorama of Philadelphia served as the centerpiece of the exhibition. Spotlights focused on specific areas of the city, and portions of the diorama then mechanically flipped over to reveal their imagined future. In the years that followed, many of the diorama’s notable features became reality, including removal of the Pennsylvania Railroad’s viaduct, popularly referred to as a “Chinese Wall”; a new, three-block-long mall north of Independence Hall; a Delaware riverfront yacht basin and promenade; and new housing in the Far Northeast.

Urban planner Edmund Bacon (1910-2005) often receives credit for the exhibit’s design, but modernist architect Oskar Stonorov (1905-70) first conceived the idea and recruited Bacon’s help. Stonorov’s business partner, the famed architect Louis I. Kahn (1901-71), also contributed to the exhibition’s design as did Philadelphia City Planning Commission (PCPC) members Robert Leonard and Robert B. Mitchell (1906-93). Their model found inspiration in General Motors’ Futurama display, an attraction of New York’s 1939 World’s Fair that showed a city of modern skyscrapers, high-speed expressways, and pedestrian skyways devoid of congestion and obsolete structures. Better Philadelphia’s creators similarly hoped to stir citizens’ imaginations while overcoming public objections to urban planning.

To assure adequate funding, Stonorov enlisted prominent Philadelphians, many of whom later held posts on the exhibition committee. These included Mayor Bernard Samuel (1880-1954) as honorary president; businessman Benjamin Rush, Jr. (corporation president); Gimbels executive Arthur Kauffman (1901-86), who donated two floors of his store for the event (vice president); Allan G. Mitchell, president of the Philadelphia Electric Company (secretary); and Philadelphia Bulletin publisher George T. Eager (committee chairman). Together, they raised more than $325,000 in public and private funds for the event.

Planners wanted to enlist public support for their vision by presenting their concepts in accessible terms, as indicated by the exhibition theme, “What City Planning Means to You and Your Children.” Taking cues from architect Daniel H. Burnham (1846-1912), whose 1909 Chicago plan was distributed to schoolchildren, Bacon and Stonorov visited elementary schools prior to the opening and asked students to draw their own plans for the future city; the drawings were later displayed at the exhibition.

Following the event, the Philadelphia City Planning Commission asked the 365,000 visitors their opinion about the exhibit’s proposals; nearly sixty-five per cent responded that they would pay higher city taxes to see the envisioned features come to fruition. By the time Bacon left as Planning Commission executive director in 1970, nearly all of the features, except for a crosstown expressway at South Street and a new ring highway system circling the city, had materialized or were under construction. Despite its short run, the Better Philadelphia Exhibition allowed planners to build consensus for reenvisioning central city functions for a new era.

Stephen Nepa received his M.A. from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, and his Ph.D. from Temple University and has appeared in the Emmy Award-winning documentary series Philadelphia: the Great Experiment. He wrote this essay while an associate historian at the Mid-Atlantic Regional Center for the Humanities at Rutgers University-Camden in 2015. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University