Blow Out

Essay

Set against the hyperpatriotic background of Philadelphia amidst the United States Bicentennial, the 1981 film Blow Out grapples with the themes of political paranoia and obsession, coupled with the demanding moviemaking process. Directed by Brian De Palma (b. 1940), it is a lesser-known De Palma thriller, inspired by the 1966 film Blow-Up.

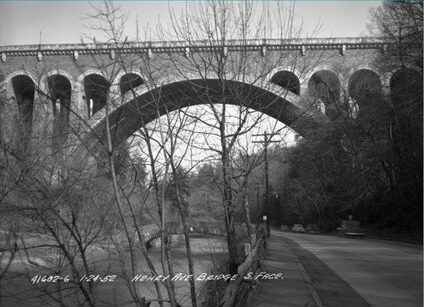

The film features John Travolta (b. 1954) as Jack Terry, a sound technician for a low-budget horror studio who, while attempting to record stock wind audio in Wissahickon Valley Park, inadvertently witnesses and records the assassination of the governor of Pennsylvania, a presidential candidate hopeful, whose car tire is shot out, forcing his car into the Wissahickon Creek. With him in the car is Sally, played by Nancy Allen (b. 1950), whom Jack manages to save. For the remainder of the film, Jack works with Sally to attempt to expose the assassination while they are each hunted down by Burke, played by John Lithgow (b. 1945), who attempts to cover his tracks by murdering women who look similar to Sally and attributing the crime to his alter ego, the Liberty Bell Strangler.

Originally, the film was to be set in Canada and titled Personal Effects. De Palma collaborated with the magazine Take One to organize a screenwriting contest to see who could best take his “dramatic framework and create a political thriller.” Although the contest found a winner, the plan fell through, possibly due to Take One’s bankruptcy. Instead, the film was set in De Palma’s hometown of Philadelphia and no other writers were credited.

Political Allusions

Using a combination of setting and plot, the film alludes to real-life, high-profile political events and artifacts such as the Zapruder film of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy (1917-63), the Chappaquiddick incident involving Edward Kennedy (1932-2009), the death of Nelson Rockefeller (1908-79), and even Watergate. De Palma attributed much of the film’s creation to his obsession with Kennedy’s assassination. In addition to Blow Up (1966), he credits the film The Conversation (1974), directed by Francis Ford Coppola (b.1939), as inspiration for the plot. Critics have also noted its commentary on the growing fear of the United States government’s clandestine ability to control the public.

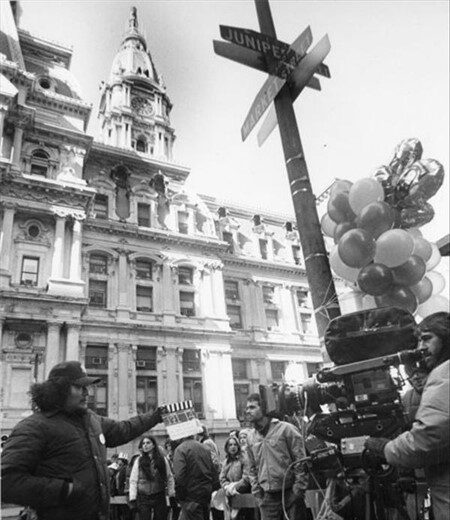

Featured in Blow Out are numerous instantly recognizable Philadelphia landmarks, including the Henry Avenue Bridge in Wissahickon Park, 30th Street Station, Reading Terminal Market, and Penn’s Landing. The film captures many locations in Philadelphia that no longer exist or have drastically changed. In one scene, Jack speaks to Sally at the Reading Terminal rail station, which was not an active railroad station beginning in 1976, the year the film is set. Later in the film, during its climax, Jack races down Market Street in his car, cutting through City Hall and driving directly through the Mummers Parade, before crashing his car into the Wanamaker’s Department Store front, which later became Macy’s. Although the film boasts a multitude of Philadelphia landmarks, no lead actors attempt the Philadelphia accent during their performance; Nancy Allen reflected that it was simply too hard for her to adopt.

The climax of the film, which most prominently features Philadelphia landmarks, also proved to be the most difficult sequence to film. On the first day of shooting the film, as Jack runs from his car and into 30th Street Station, John Travolta fell and twisted his ankle, creating an obstacle for both himself and De Palma. Later, after filming had wrapped, negatives for the Wissahickon Park scene and the chase through the Mummers Parade were stolen out of a truck, forcing both the cast and crew to return to Philadelphia to reshoot the parade sequence. The chase scene ends with a large parade at night on the Delaware River waterfront. According to De Palma, it took the crew an entire night just to achieve the correct lighting for this scene.

Later Acclaim

Blow Out garnered renewed admiration in 2011 following its rerelease by the Criterion Collection, a distributor of prestige home video. Critics’ responses at the time of its original release ranged widely between high praise and dismissal as a “cheap genre film.” Roger Ebert (1942-2013), Pauline Kael (1919-2001), and Quentin Tarantino (b. 1963) were among the film’s staunchest defenders, with Tarantino once claiming the film “is one of the greatest movies ever made.”

Audiences were not as kind. The film cost $18 million to make and recouped only $13 million, a box office failure that has been largely attributed—even by De Palma himself— to the grim ending involving a character’s death. The film’s summer release instead of fall, as De Palma and Allen wanted, may have negatively affected its reception by audiences seeking lighter fare. Following suit, the 1982 award season was equally unimpressive. Only Vilmos Zsigmond (1930-2016), the film’s cinematographer, earned a National Society of Film Critics nomination for Best Cinematography. Although critics and audiences alike may not have initially appreciated Blow Out for its artistic merits, the film’s sweeping and recognizable political intrigue and De Palma’s eye for his hometown successfully created one of the most comprehensive visual time capsules the city of Philadelphia has to offer.

Matthew Midgett is a Philadelphia resident, writer, and second-year student in Rutgers-Camden’s English and Media Studies Master’s program. His interests include Gothic literature, Philadelphia film, and Marxist theory. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2022, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History