Chinatown

By Kathryn Wilson | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

Settled by Chinese migrants in the 1870s, Philadelphia’s Chinatown grew over the course of the twentieth century from a small ethnic enclave on the outskirts of Skid Row to a vibrant family community in the heart of Center City. Threatened by urban renewal in the 1960s and 1970s, Chinatown residents marshaled the redevelopment process to rebuild and expand their community over the course of the late twentieth century. This legacy of activism continued to inform struggles against gentrification and for affordable housing, education, and community self-determination. While Chinese and other Asian immigrants dispersed throughout the greater Philadelphia area, Chinatown remained as a central touchstone for Asian life in the region.

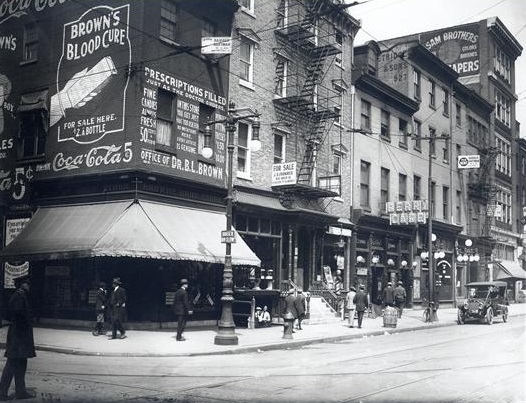

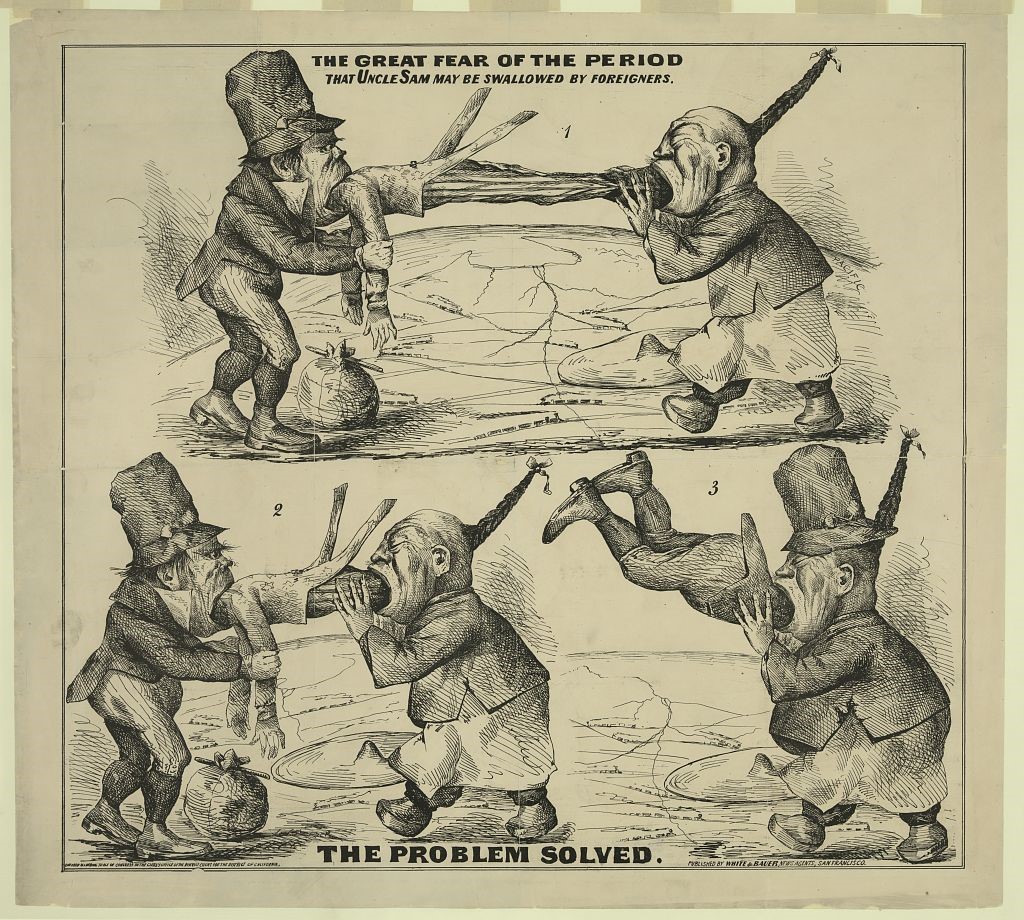

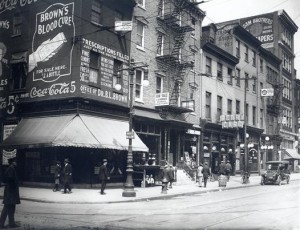

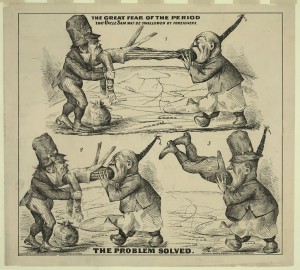

Philadelphia’s Chinatown had its roots in the “great driving out” of Chinese from the American West in the 1870s and 1880s, when Chinese migrants fled racist backlash and violence. During these decades Chinese merchants and laundry men established a small enclave along the 900 block of Race Street, on the outskirts of the central business district. At a time when Philadelphia was the “Workshop of the World” and European immigrants’ lives were structured around the proximity of home and work, Chinese immigrants were restricted to domestic service, laundry work, and small commercial ventures such as import/export gift shops, groceries, and, later, restaurants. Although many Chinese men lived and worked in laundries across the city, they were not integrated into these neighborhoods; Chinatown functioned as their true home and the center of Chinese community in the city.

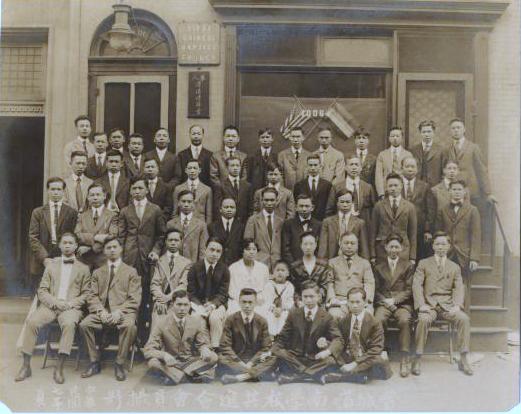

Life in Chinatown at the turn of the twentieth century was structured around the spaces of shops, restaurants, communal boarding houses, and common rooms (or fongs). Social life largely focused on the many family and business associations, later consolidated under the umbrella of the Chinese Benevolent Association. Restrictive U.S. immigration laws such as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 prevented all but merchants from bringing families, creating a hierarchical “bachelor society” of men living as single in extended kin arrangements. From the 1910s to the 1940s Chinese Americans expanded their presence around 900 Race, occupying adjacent blocks amid a multiethnic population, making a home amidst the city’s Skid Row to the east and “Tenderloin” district to the west. This community publicly manifested its ethnic character in enactments of Chinese identity such as funeral processions, political demonstrations, and New Year celebrations, all of which provided exotic spectacle for non-Chinese Philadelphians. On the other hand, Chinatown also gained visibility as a “nuisance” and deviant vice-ridden area. It was frequently raided by police in the early 1900s during the so-called “tong wars.” Tongs were traditional Chinese associations adapted to serve business and social needs in America, but they gained a criminal image informed by negative Orientalist stereotypes.

Community Transformation

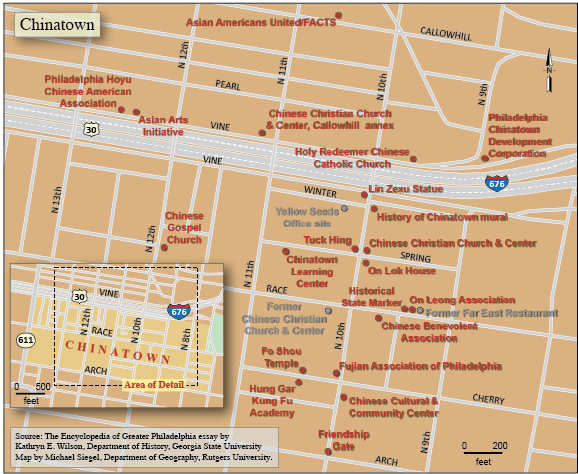

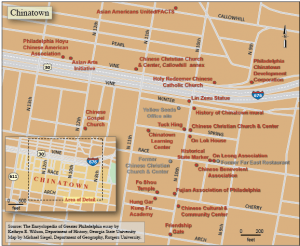

Liberalized immigration policies after World War II allowed Chinese Americans to bring wives from China. This initiated a new wave of immigration to Philadelphia that transformed Chinatown into a family-oriented community. Churches, businesses and social/cultural organizations were established to improve neighborhood life, preserve Chinese culture, and provide services to the growing number of new immigrants. Holy Redeemer Chinese Catholic Church at Tenth and Vine Streets dates to this period, as does the Chinese Christian Church and Center at Tenth and Spring Streets. From 1940 to 1980, the boundaries of Chinatown expanded greatly north to Wood Street, south to Arch Street, and east-west from Eighth to Twelfth Street as this area became more or less exclusively Asian in character.

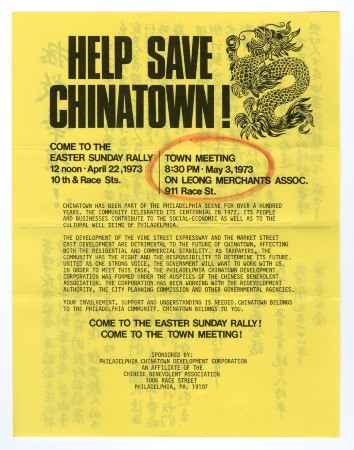

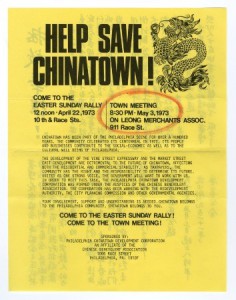

This growth of Chinatown coincided with emerging city plans, as early as 1945, for a crosstown expressway and other urban redevelopment projects in and around the neighborhood core. From the mid-1960s through the 1980s, urban renewal projects laid waste to each of Chinatown’s borders. An expansion of Independence Mall closed off the eastern boundary, The Gallery/Market East mall the southern. Later in the 1980s the construction of the Convention Center occupied a western border on Eleventh Street. Most significantly, in 1966, Chinatown residents learned that the construction of an expressway along Vine Street would entail the destruction of the beloved Holy Redeemer Chinese Catholic Church and School. A young widow, Cecilia Moy Yep (b. 1929), began organizing residents to fight the expressway plan. With George Moy (b. 1925), Yep founded the Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation (PCDC) in 1969. PCDC was joined in the fight by the more traditional Chinese Benevolent Association and a radical student group, Yellow Seeds, whose Maoist and Black Power-influenced activism embraced the fight to save Chinatown as well as providing community services including a health clinic, newspaper, and breakfast programs. Yellow Seeds’s slogan, “Same Struggle, Same Fight,” linked the fight in Chinatown to the struggles of “Third World peoples” throughout the city and worldwide.

A turning point in the expressway battle came on July 1973, when a group of young people defied the demolition cranes and climbed up onto a pile of rubble at Tenth and Winter Streets to protest the destruction of houses in their neighborhood. The homes had been claimed through eminent domain to make way for the expressway. The incident drew the attention of the local media (one television reporter joined the youth atop the pile) and spurred the city’s interest to redevelop the area. Using a variety of tactics, including enforcement of the recently enacted federal Environmental Protection Act (1970), which mandated environmental impact studies for communities affected by the expressway route, activists delayed the project for over a decade, allowing for modifications of the plan. Their success saved the church and launched new and more inclusive leadership in Chinatown.

Progress in the 1970s

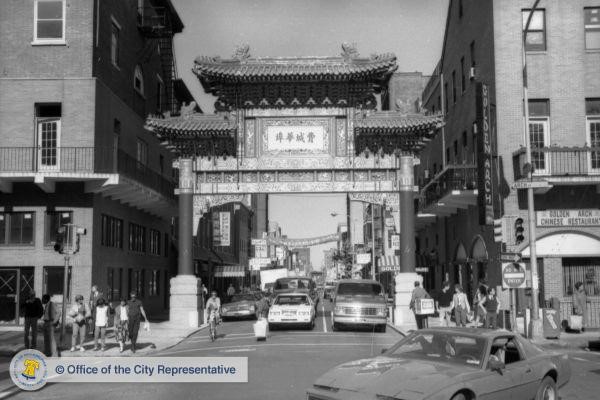

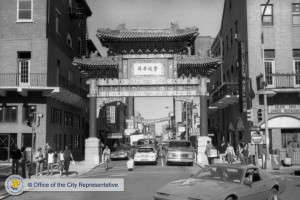

The fight against the expressway also transformed Chinatown’s relationship with the City of Philadelphia. In the mid-1970s PCDC collaborated with the City Planning Commission on a study for Chinatown (the Chadbourne Report) that outlined redevelopment activities including new housing, streetscape improvements, and a senior center. Working through private/public partnerships from the 1970s to the present, PCDC systematically targeted land previously claimed by demolition, secured special zoning for Chinatown, and worked as a developer to obtain Redevelopment Authority-controlled lots. It completed various housing and mixed residential-commercial structures, and an “authentic Chinese” Friendship Gate. Under the leadership of Reverend Yam Tong Hoh (1898-1987), of the Chinese Christian Church and Center, the community created On Lok House, a senior citizen residence and center. The Friendship Gate became the most visible external symbol of the community. At the same time, housing projects articulated a vision of a “living community” that emphasized housing, family, and community institutions “beyond the restaurants” and the neighborhood’s status as a tourist destination.

To protect this vision of a “living community,” Chinatown residents and supporters continued to draw on this history of activism to mobilize against urban renewal schemes that threatened the residential character of the neighborhood. In 1993, residents organized to push back against a proposal for a federal prison near Holy Redeemer. In 2000, a complex coalition including PCDC, Asian Americans United, the Chinese Benevolent Association, new immigrant businesses, and other individuals and organizations across the city–Asian and non-Asian–organized to oppose a proposal for a baseball stadium at Twelfth and Vine Streets. This opposition aimed to protect Chinatown housing and community spaces adjacent to the stadium site and reaffirmed the cultural and historical significance of the neighborhood for the region as a whole.

The stadium fight also highlighted the importance of the area north of Vine Street−dubbed “Chinatown North”−for Chinatown’s future. Chinatown North emerged as a site of neighborhood expansion beginning in the late 1990s, when PCDC located its offices and a housing development on Ninth Street north of Vine. The Chinese Christian Church and Center opened a new congregation on Vine Street in 2007. Other organizations such as Asian Americans United and the Asian Arts Initiative located their facilities north of Vine Street. Also in 2007, Asian Americans United also opened the Folk Arts and Cultural Treasures Charter School, or FACTS, the first public school in Chinatown, in an empty factory at 1023 Callowhill Street.. Chinatown North continued to be home to small-scale manufacturing and product warehousing ventures, serving as a “back end” for the Chinatown retail and restaurant sectors. Plans called for a new high-rise community center, known as Eastern Tower, for the historic corner of Tenth and Vine Streets, solidifying the historical significance of this area for the Chinatown community.

Chinatown Expands and Diversifies

Chinatown continued to be a destination and launching point for new immigrants. After the Hart-Celler Act of 1965, when U.S. immigration law removed restrictions on immigration from Asia, the greater Philadelphia area incorporated ongoing waves of immigration from China and other Asian nations. An influx of immigrants from Hong Kong led to the growth of Chinatown in the 1970s. In the 1980s, resettled refugees from Vietnam, many of them ethnic Chinese, diversified the population of Chinatown and created many new businesses. Most of the newcomers to Chinatown after the 1990s were Mandarin- or Fujianese-speaking immigrants from Fujian. Differences of language and custom presented challenges for local churches and organizations seeking to help or represent new immigrants. Many recent immigrants retained a strong connection to their country of origin. Among them, entrepreneurs brought significant capital to start businesses and invest in the neighborhood economy. They also reanimated traditional customs and celebrations such as Chinese New Year and the Mid Autumn Festival, celebrated each year in Chinatown. A new annual parade for the Hoyu Folk Culture Festival, sponsored by the Philadelphia Hoyu Chinese American Association, honored the founder of Fuzhou, the capital of Fujian Province in southeastern China.

In the twenty-first century, Chinatown embodied a pan-Asian identity, serving as a central touchstone for a larger cultural community of Asians around the greater Philadelphia area. Organizations such as Asian Americans United and the Asian Arts Initiative reflected this new pan-Asian focus. According to the 2010 Census, the bulk of Chinatown residents were still Chinese, although the area was also 4.4 percent Asian Indian, 4 percent Korean, 2 percent Vietnamese, and 1 percent Filipino and Japanese, with smaller numbers of Indonesian, Malaysian, Cambodian, Pakistani, and Burmese residents. Chinatown also housed Vietnamese, Burmese, Korean, Japanese, and Malaysian businesses. This diversity reflected larger immigration trends. The 2000 Census reported 17,390 Chinese in Philadelphia (31,663 in the five-county region), and this figure rose to 29,396 in 2010 (with 53,133 in the five-county region). In 2011 the Metro Chinese Weekly estimated that more than 150,000 Chinese lived in the Greater Philadelphia metropolitan region, most of them outside Chinatown. The larger Asian population likewise grew exponentially in the last few decades. In 2011, Asian immigration accounted for 39 percent of Philadelphia’s foreign-born population and Asians were 6.3 percent of the city’s population. Chinese and other Asians lived in South Philadelphia, West Philadelphia, the Northeast (particularly Mayfair), and suburban areas, with a large percentage in Montgomery County.

Despite this dispersed settlement, by the first decades of the twenty-first century Philadelphia did not develop a “second Chinatown” like New York’s Queens, and Chinatown remained a primary entry point for immigrants and a symbol of Asian American history, struggle, and resilience in the region. New immigrants used Chinatown as a base, traveling to and from New York’s Chinatown, an important source of labor and migration for greater Philadelphia. Local and regional immigrants from New Jersey and Pennsylvania came to Philadelphia’s Chinatown on the weekends to shop, dine, attend events, and, on Sundays, go to church. Family banquets and other significant gatherings continued to occur in Chinatown, and a majority of traditional family, regional, and business associations remained located there. Many aging or retired Chinese Americans expressed a desire to retire in Chinatown, if affordable housing were available. Younger or second-generation immigrants continued to open businesses in Chinatown, some of which catered to their demographic, and Chinese students attending local universities attended Chinatown’s churches and shopped in neighborhood businesses. Others considered Chinatown a haven for all immigrants (regardless of national origin) in the city, a “safe space” from discrimination or harassment. In addition, Chinatown’s workforce extended beyond those of Asian origin. Many restaurant workers, for example, hailed from Mexico or Central America, and Spanish became as common in Chinatown’s kitchens as Cantonese once was.

Chinatown’s small size and strong sense of history and community made it resilient in the face of historic challenges. Nevertheless the community remained vulnerable to larger outside forces. In the twenty-first century, gentrification presented an ongoing threat, both in the Chinatown core and Chinatown North. Approximately 74 percent of the businesses located in Philadelphia’s Chinatown were small or local businesses, including a core group of family-owned restaurants. But despite increasing immigration to Philadelphia region, the foreign-born population in Chinatown decreased from 42 to 33 percent between 2007 and 2011 and family households also declined (from 61 to 46 percent between 1990 and 2010, a significant change). New condominium developments occurred at a brisk rate, adapting old hotels and factories and leading to a dramatic threefold increase in home values. Chinatown’s residents and advocates continued to draw on a legacy of activism and struggle to develop the community and secure a future “beyond the restaurants.”

Kathryn Wilson is an Associate Professor of History at Georgia State University. She previously worked at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and is the author of Ethnic Renewal in Philadelphia’s Chinatown: Space, Place and Struggle. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Sugarhouse Seeks Liaison to Asian Community (WHYY, November 15, 2010)

- Developer Plans Casino Complex for Inquirer-Daily News Site (WHYY, April 12, 2012)

- Philadelphia Suns Mark Four Decades of Basketball and More in Chinatown (WHYY, September 19, 2012)

- New Housing Facility in the Name of Pope Francis Opens in Philadelphia (WHYY, May 4, 2016)

- Space is the Place: The History of Philadelphia's Chinatown (WHYY, May 17, 2016)

- Echoes of Three Centuries Take Female Form to Express Callowhill's Harsh History (WHYY, October, 7, 2016)

- Celebrating Tradition--and a Southeastern China God's Birthday--in Philly (WHYY, March 31, 2019)

- Philadelphia secures $158 million for Chinatown Stitch project (WHYY, March 11, 2024)

- No Arena Coalition celebrates win over threat to Chinatown and Community (BillyPenn/WHYY, January 13, 2025)