Civil Rights (LGBT)

By Dan Royles | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

In the second half of the twentieth century, a growing number of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) Americans claimed political rights as people whose same-sex desire or gender presentation challenged prevailing social mores. As movements for African American, Latino American, and women’s rights gained traction and visibility, so too did movements for LGBT civil rights. In this context, LGBT activists in Greater Philadelphia pressed for the extension of the rights and protections that would signal their inclusion in American society. By the time the Supreme Court legalized same-sex marriage in the landmark case of Obergefell v. Hodges in 2015, LGBT Philadelphians could point to victories at the local and state levels, achieved through a combination of theatrical protest and political advocacy. At the same time, however, Pennsylvania lagged behind New Jersey, Delaware, and other northeastern states in the civil rights afforded to LGBT residents.

Displays of homosexual affection and cross-dressing had been part of public life in cities like Philadelphia going back to the colonial period. However, it was not until the decades following World War II that such practices, and the sexual and gender identities associated with them, became explicitly politicized. During the 1950s and 1960s, the first gay and lesbian civil rights protests in Philadelphia reflected the growing political consciousness of homophile activists. These demonstrations also borrowed tactics from the much more widespread movement for Black civil rights unfolding at the same time.

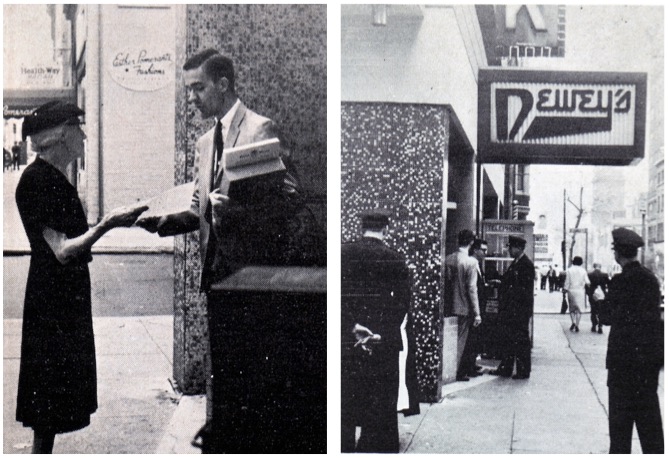

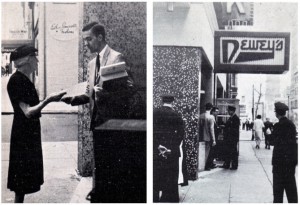

The first documented public protest for LGBT civil rights in the city began with a sit-in. On April 25, 1965, Dewey’s, a diner near Rittenhouse Square with a large clientele of gay youth, drag queens, and sex workers, began refusing to serve customers who appeared to be gay or lesbian, as well as those wearing clothing that did not match their gender. After more than 150 such customers had been denied service, three teenagers refused to leave and were arrested. Over the next five days, members of the Janus Society, a local gay and lesbian political group, protested outside of Dewey’s, and distributed their literature to passersby. On May 2, one week after the first sit-in, a group of teenagers staged a second protest. This time, no arrests were made, and the restaurant resumed serving LGBT customers.

Demonstrations at Independence Hall

Although the Dewey’s sit-ins showed that some gay and lesbian activists were willing to stand up for those who publicly dressed and acted in unconventional ways, most hewed to a politics of respectability. They described themselves as “homophiles” rather than “homosexuals” in order to distance themselves from sexual acts, a strategy that many saw as a necessary step toward inclusion in American society. The Annual Reminder demonstrations, held in front of Independence Hall every Fourth of July from 1965 to 1969, also reflected this concern. As they protested anti-sodomy laws, the firing of gay men and lesbians from federal employment, and their exclusion from military service, Annual Reminder marchers dressed professionally and in ways that conformed to gender expectations, with men in suits, jackets, and slacks, and women in dresses. The choice of time and place for the demonstrations underscored the marchers’ political claims. In contrast to the counterculture and anti-war movements, which criticized U.S. society as crassly commercial and militaristic, Annual Reminder marchers situated themselves squarely within American identity by marching on July Fourth in the place where the nation’s founding documents had been written and signed.

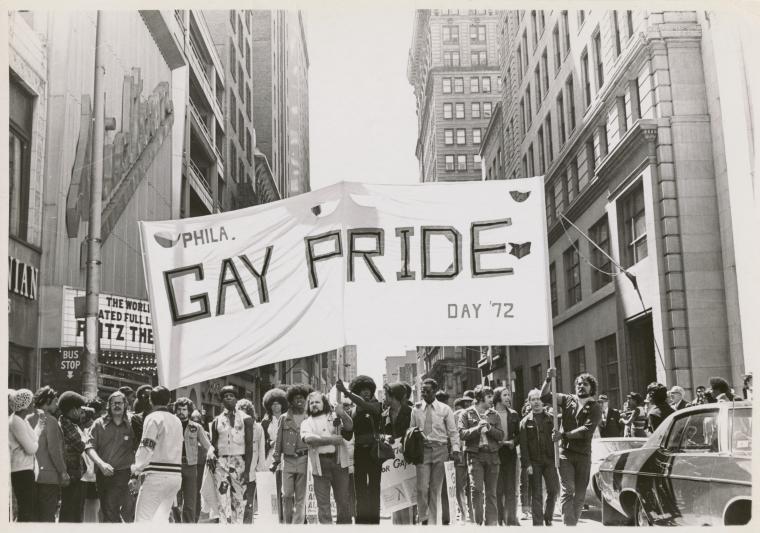

In the early 1970s, homophile activism gave way to gay liberation, although the more radical goals and tactics of gay liberation groups did not preclude their involvement in conventional politics. The Homophile Action League and the Gay Activists Alliance, which staked out more militant positions than their Annual Reminder predecessors, pressed local lawmakers to extend Philadelphia’s anti-discrimination protections to gay men and lesbians. In 1974 the City Council held hearings on a bill to add sexual orientation to the city’s Fair Practices Ordinance, to outlaw anti-gay discrimination in employment, housing, and public accommodations. However, with vocal opposition from both council members and religious leaders, including members of Philadelphia’s Black clergy, the bill failed to make it out of committee. Opponents of the measure contended that race and sexual orientation were fundamentally different, and questioned gay and lesbian activists’ attempts to claim protections as an aggrieved minority alongside African Americans, Jews, and other historically persecuted groups.

Local and State Victories

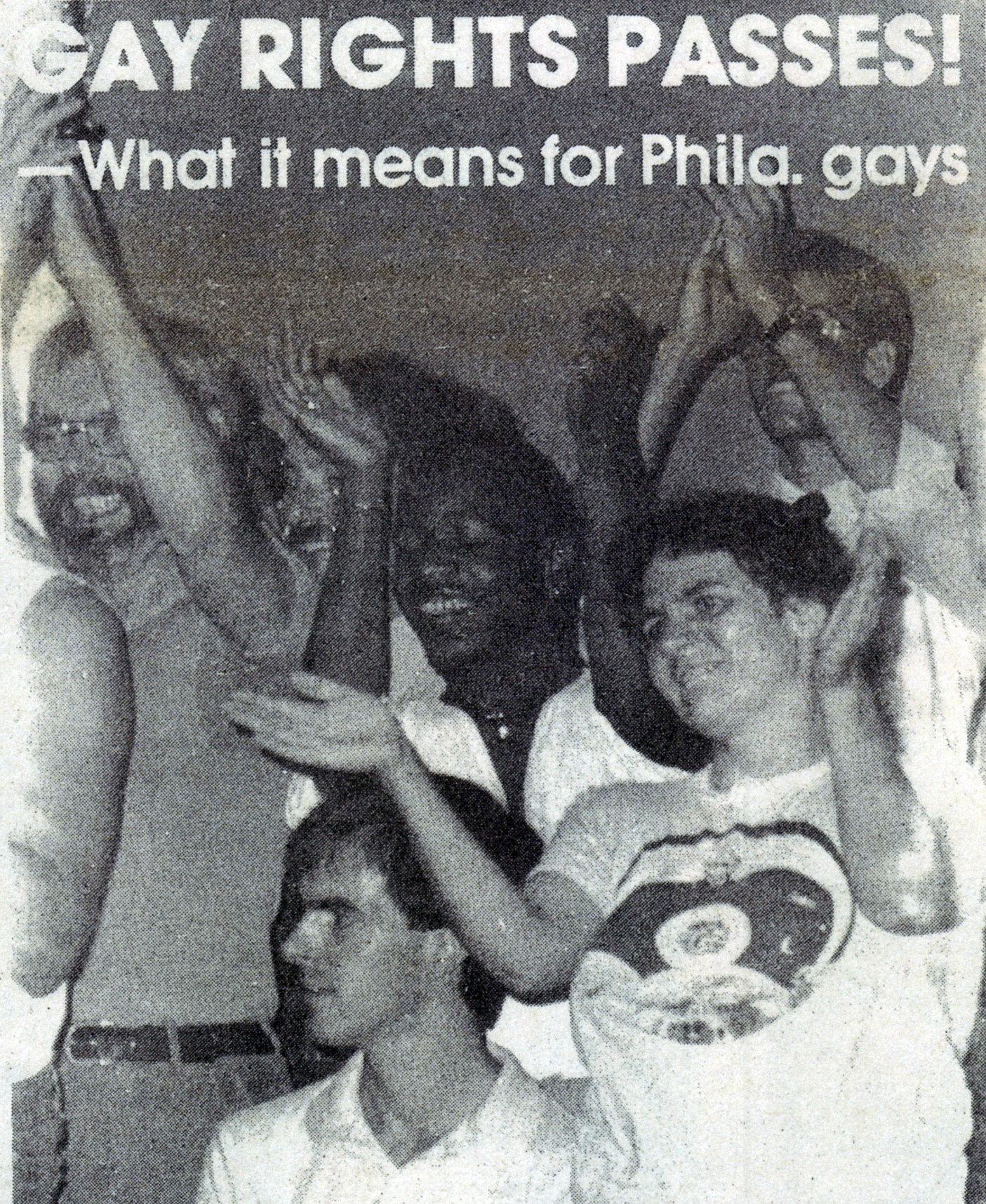

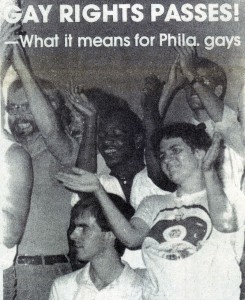

In 1978, activists with the Christian Association, a philanthropic group at the University of Pennsylvania organized the Philadelphia Lesbian and Gay Task Force (PLGTF) to advocate for sexual rights in the city. Under the leadership of Reverend James Littrell (b. 1943) and Rita Addessa (b. 1945), the group’s first two executive directors, PLGTF forged alliances with local African American political and religious leaders. When a second effort to amend the Fair Practices Ordinance went before city council in 1982, W. Wilson Goode (b. 1938), the city manager who later became Philadelphia’s first African American mayor, and members of the newly visible Black gay community testified in support. With broadened support for gay and lesbian civil rights, the bill passed. Harrisburg, the state capital, revised its own City Code to include protections against discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity in 1983. Lancaster similarly added sexual orientation as a protected class to its Codified Ordinances in 1991. York added an anti-discrimination measure covering sexual orientation to its City Code in 1993, and a measure covering gender identity in 1998.

In the 1990s, LGBT activists, along with allies in local government, pressed for domestic partnership laws in the city. City council member Angel Ortiz (b. 1941) and Mayor Edward G. Rendell (b. 1944) introduced different bills providing for domestic partnership recognition and benefits in 1993. The bills failed as opponents, including City Council President John F. Street (b. 1943), argued that domestic partnerships would undermine traditional family structures. In June 1996, Rendell signed an executive order granting benefits to the domestic partners of some five hundred city employees, representing only a fraction of the almost 26,000 working in local government. Street vocally opposed the measure, and joined with Catholic Archbishop Anthony Bevilacqua (1923-2012) and the Black Clergy of Philadelphia and Vicinity to reverse the order. Rendell refused, and a trio of domestic partnership bills passed the council in 1998, granting health and pensions benefits to the “life partners” of city employees.

In 2013, the City Council expanded life partnership provisions to include hospital visitation with the passage of the LGBT Equality Bill, which also added gender identity to the city’s non-discrimination ordinance and offered tax credits to companies that expanded their employee benefits to include coverage of transgender-specific health care and health benefits for same-sex domestic partners. In May 2014, a federal district court judge ruled that the state’s ban on same-sex marriage was unconstitutional. The following year, in June 2015, the United States Supreme Court invalidated similar state-level prohibitions clearing the way for same-sex marriage across the country.

The twenty-first century also brought a greater focus on the rights of transgender people. In 2009, Philadelphia activists formed Riders Against Gender Exclusion (RAGE) with the goal of eliminating gender identification stickers from Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority (SEPTA) TransPasses. RAGE members argued that the stickers opened a risk of embarrassment and harassment of people whose outward gender expression did not match the stickers on their cards. Over the course of a three-year campaign, the group collected stories of harassment from transgender and gender non-conforming SEPTA riders, staged a protest drag show inside a SEPTA station, and interrupted a public SEPTA hearing to present officials with a six-foot-long “RAGE Rider’s Bill of Rights” outlining their demands. On July 1, 2013, for the first time in thirty-two years, SEPTA riders were able to use TransPass cards without the gender identification stickers.

Hate Crime Legislation

Beginning in the late 1980s, Philadelphia LGBT activists and their allies also worked to add sexual orientation and gender identity to existing hate-crime laws. The Philadelphia Lesbian and Gay Task Force made anti-gay violence a political issue as early as 1986, and in 1990 state representative Babette Josephs (b. 1940) introduced an unsuccessful bill that would have extended the state’s hate-crime law to cover sexual orientation. The 1998 killing of University of Wyoming student Matthew Shepard (1976-98), which became a national news story, revived local interest in the issue. Weeks after Shepard’s death, the Philadelphia Lesbian and Gay Task Force organized a protest at the Liberty Bell to call for a state-level hate-crime law covering sexual orientation. In 2002, after the brutal beating in Middleburg, Pennsylvania, of a man who was perceived to be gay, the state legislature finally passed a bill that expanded Pennsylvania’s Ethnic Intimidation Act to include sexuality and gender identity. However, the state supreme court struck down the 2002 expansion of the law in 2008.

Following a highly publicized attack on two gay men in Center City in September 2014, the Philadelphia City Council passed its own hate-crime bill. Pennsylvania lawmakers also introduced, but never voted on, hate-crime legislation covering sexual orientation and gender identity at the state level. In contrast, New Jersey added sexual orientation to its hate crime statute in 1990, and did the same for gender identity in 2008. Wilmington, Delaware, added a provision for hate crimes based on sexual orientation to its City Code in 1992. The state of Delaware added sexual identity to its own hate crime statute in 1998, followed by gender identity in 2013.

Pennsylvania similarly lagged behind its neighbors in guaranteeing LGBT civil rights. Although Pennsylvania became the first state to ban sexual orientation discrimination in state employment, under a 1975 executive order by Governor Milton Shapp (1912-94), as of March 2016, Pennsylvania had no law barring discrimination against LGBT people in housing, employment, and public accommodations. In contrast, New Jersey’s Law Against Discrimination included provisions for sexual orientation beginning in 1991 and for gender identity and expression beginning in 2006. Delaware passed legislation barring discrimination based on sexual orientation in 2009, and a similar law against discrimination based on gender identity and expression in 2013. In Pennsylvania, state legislators in 2015 continued to press for the Pennsylvania Fairness Act, which would update a 1995 state law against discrimination to include sexual orientation, as well as gender identity and expression.

The struggle for LGBT civil rights in Philadelphia after World War II yielded important gains for people who had been vulnerable to discrimination and harassment on account of their sexual and gender identities. Activists also won recognition for same-sex couples, first in Philadelphia, then in Pennsylvania, and, finally, nationwide. In so doing, they challenged prevailing ideas of sexual citizenship, and laid claim to both symbolic and material forms of belonging in American society. At the same time, the periodic failures and reversals suffered by activists exposed the extent to which LGBT Philadelphians were impacted by local, state, and federal policies—and the work that remained to be done.

Dan Royles is Assistant Professor in the Department of History at Florida International University. His first book, To Make the Wounded Whole: African American Responses to HIV/AIDS, is under advance contract with the University of North Carolina Press. (Author information current at time of publication.)

(Editor’s note: Additional future essays will cover civil rights for African Americans, women, and persons with disabilities.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Brian Sims breaks the mold, unseats a long-time incumbent (WHYY, April 25, 2012)

- Remembering Gloria Casarez: LGBT leader, friend, Philadelphian (WHYY, October 20, 2014)

- Pennsylvania Senate to try again to outlaw LGBT discrimination (WHYY, June 30, 2015)

- Despite controversy, Philly Pride celebrates history and the advance of LGBT rights (WHYY, June 10, 2016)

- Equality Forum focuses on LGBT community's advances, challenges (WHYY, July 26, 2016)

- Historical marker dedicated to Delaware-born gay rights activist Gittings (WHYY, July 27, 2016)

- Hundreds rally to support trans men and women in Philly (WHYY, October 23, 2018)

Links

- Philadelphia LGBT History Project (OutHistory.org)

- The First Gay Sit-in Happened 40 Years Ago (History News Network)

- The John Fryer papers and the Dr. Anonymous affair (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Teaching LGBT Rights (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Equality Forum

- That's So Gay: Outing Early America (Digital Exhibit, Library Company of Philadelphia)

National History Day Resources

- Frank Kameny Correspondence (Kameny Papers)

- Digitized photographs from the Barbara Gittings and Kay Tobin Lahusen gay history papers and photographs (New York Public Library)

- Karen F. Ulane, Termination Letter, April 24, 1981 (National Archives)

- Karen F. Ulane, Second Termination Letter, March 25, 1982 (National Archives)

- Excerpt of the transcript with direct examination of Karen Fraces Ulane, April 5, 1984 (National Archives)

- Mayor Edward G. Rendell, Executive Order regarding domestic partnerships, June 7, 1990 (Phila.gov)

- Obergefell v. Hodges Syllabus, decided June 26, 2015 (Supremecourt.gov)