Civil Rights (Women)

Essay

The struggle for women’s equality and civil rights started early in the Philadelphia region as women organized for education, property ownership, political power, economic opportunity, and freedom. In the colonial era, Quakers took the vanguard in women’s rights among European settlers by promoting women as ministers and overseers of discipline within the Society of Friends. Nevertheless, William Penn (1644-1718) and other founders of West New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Delaware followed English common law and culture to block women from suffrage, participation in government, control of property and wages, and guardianship of children. Many affluent colonists on both sides of the Delaware River denied enslaved women and men an even broader spectrum of human rights. During the revolutionary and antebellum periods, however, female organizations demanded women’s rights and the abolition of slavery. Their efforts provided a foundation for the 1920 ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment for woman suffrage and the feminist movements of the late twentieth century.

Among Lenapes who dominated the region when European colonizers arrived in the 1600s, women and men held equal status while performing different social and economic roles. Women nurtured children and worked as agriculturalists, controlling arable land and the distribution of corn and other food they produced, while men hunted, fished, and provided military defense. Within their matrilineal communities, elder women supervised the succession from one sakima (or leader) to the next through the maternal line. Evidence is limited about how frequently Lenape women served as sakima because male European colonialists generally failed to note if they negotiated with women, but some documents indicated female participation in treaties. For example, the female sakima Ojroqua (c. 1640-1700) with other Lenape leaders attended a 1670 conference with representatives of James, Duke of York (1633-1701) and signed land conveyances in 1677 to the West Jersey proprietors and, in 1678, to Elizabeth Kinsey (c. 1660-1720) for Petty Island.

European immigrants brought to North America a gender ideology built on contradictory concepts that women were inferior to men yet fully capable of fulfilling male responsibilities when necessary. Europeans viewed men as dominant and central, while women held subordinate, marginal characteristics and roles. The English common law and political culture employed this ideology to deny women equal economic, political, and legal rights. When a couple married, under the concept of unity of person (coverture), the wife legally became a feme covert, yielding to the husband her independent rights to buy and sell property, make a will, enter into contracts, control her earnings, claim the value of her contributions to joint business ventures, sue in court, and act as legal guardian of their children. An unmarried woman, whether single or widowed, could take these actions as feme sole, and a married woman could assume this authority if her husband became incapacitated or was absent for a long period of time. During the colonial period, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware followed the English common law to reserve a widow’s right to dower, or one-third of the couple’s real estate, during her lifetime, regardless of whether the husband left a will. If he died intestate, she also received one-third of personal estate, but he could deny her that portion if he wrote a will.

The System of Perpetual Enslavement

Enslaved women and girls in the Delaware Valley, of whom most were Black people brought from Africa and the West Indies but also included some Native Americans from the Carolinas, endured forced labor as domestic servants, cooks, and agricultural workers. Under the system of perpetual bondage, enslaved people in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware could not own property, obtain wages, or decide where they would live and work. They often suffered inadequate food, clothing, and shelter, and had no right to marry, exert parental authority, or receive justice in the courts. In particular, Black women were subjected to rape and other physical assault by their enslavers and neighboring whites, with no protections under the law. As mothers, they faced exploitation for both their labor and reproductive capabilities, as their children added to the enslavers’ income and estate and could be sold away at any time. Provincial laws impeded the path to freedom: Pennsylvania required enslavers to post a £30 bond before manumitting a Black woman, man, or child; Delaware mandated bonds of £30 to £60; and New Jersey demanded £200 bonds. The colonies subjected free Black women and men to some legal restrictions placed on enslaved people, and New Jersey prevented Black people from owning land.

Despite Philadelphia’s central role as host to the Continental Congress and the famous advice of Abigail Adams (1744-1818) to her husband John Adams (1735-1826) to “remember the ladies” by ending coverture in drafting new laws, the American Revolution had little immediate impact on women’s economic and political rights. The states generally followed English common law in sustaining coverture and the widow’s lifetime share of one-third of real estate. American lawmakers ignored women’s contributions to the military and home front, defining political participation and suffrage as male prerogatives. New Jersey was a partial exception as its 1776 constitution allowed female property holders to vote until the legislature removed that power in 1807.

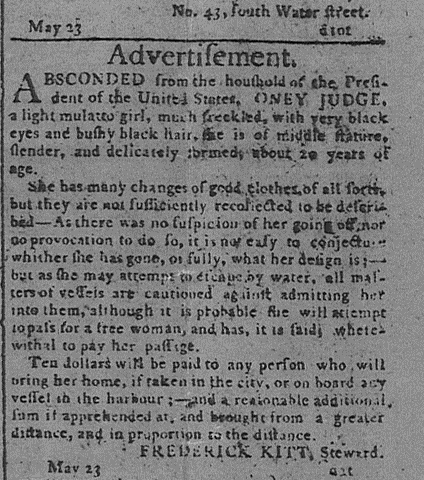

Revolutionary rhetoric for liberty from British oppression intersected with vigorous Black resistance and Quaker opposition to enslavement, influencing Pennsylvania legislators to pass the 1780 act for gradual abolition. New Jersey waited until 1804 to enact a similar law, while Delaware adopted none. The Pennsylvania act freed children born after March 1, 1780, to enslaved mothers, requiring long terms as indentured servants. Nevertheless, thousands of Black women and men throughout the United States obtained release or escaped enslavement during and after the Revolution, many establishing homes in Philadelphia and its hinterland. Ona Judge (1773-1848), for example, fled her enslavers President George Washington (1732-99) and Martha Washington (1731-1802) in Philadelphia in 1796 when she learned that they intended to transfer her to their granddaughter in Virginia. Judge gained assistance from members of the city’s growing free Black community as she escaped by ship to New Hampshire to avoid recapture.

Women Form Civic Associations

With the governmental shift during the American Revolution, women sought responsibilities as equal citizens in the new republic. Barred from standing for office or, in most jurisdictions, from voting, they formed civic associations to promote political and social goals such as assisting the Continental Army, benevolence, temperance, abolition of enslavement, and women’s rights. In 1780, Esther DeBerdt Reed (c. 1746-80), wife and political collaborator of Joseph Reed (1741-85), president of Pennsylvania’s Supreme Executive Council, published her essay “The Sentiments of an American Woman.” Believing women had full-fledged political roles as citizens, DeBerdt Reed called together the Ladies Association of Philadelphia to canvass for funds door-to-door for the Continental Army. When she urged women in other states to follow suit, schoolteacher Mary Dagworthy (1748-1814) of Trenton inspired women from thirteen counties to join the New Jersey Association and solicit funds.

In December 1833, a group of energetic African American and white women established the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society (PFASS), asserting women’s right to work collectively for social, legal, and economic change. Like other supporters of William Lloyd Garrison (1805-79), they promoted immediate emancipation and an end to discrimination against free Black people. Among the group’s activists were Black leaders Margaretta Forten (1806-75), Harriet Forten Purvis (1810-75), and Sarah Mapps Douglass (1806-82); Quakers Lucretia Mott (1793-1880) and Sarah Pugh (1800-84); and Mary Grew (1813-96), of a Baptist family. PFASS members initially circulated antislavery petitions and recruited members by hosting speakers. Over time, when Congress rejected petitions and Garrisonian abolitionists shunned politics, PFASS members focused on their annual fair, where they sold needlework and farm produce of abolitionist women and men throughout southeastern Pennsylvania and southwestern New Jersey. By contributing a large portion of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society’s budget, PFASS gained leadership positions for Mott, Pugh, and Grew in the male-dominated state organization.

In the late 1840s and 1850s, PFASS members also played a vital role in launching the women’s rights movement, as Lucretia Mott joined Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815-1902) in assembling the Seneca Falls, New York, convention. Stanton wrote the 1848 Declaration of Sentiments, modeled on the Declaration of Independence (1776), protesting the denial of women’s suffrage; participation in government; ownership of property; equality in separation and divorce; access to well-paying employment, colleges, and education in the professions; and leadership in most religions. The signers insisted that women receive all rights as equal citizens, noting that anything less destroyed their self-confidence and self-respect. This first feminist movement organized through state and national conventions, attracting large audiences to hear speakers on relevant issues. Philadelphian Sarah Tyndale (1792-1859), a wealthy businesswoman and reformer, served as vice president at the first national convention in 1850 in Worcester, Massachusetts. Mott presided in 1852 at the first Pennsylvania convention in West Chester and, in 1854, with Sarah Pugh organized the fifth national convention at Sansom Street Hall in Philadelphia.

Married Women’s Property Act of 1848

In response to women’s rights activists, increasing urbanization, and demographic and economic change, state legislatures gradually addressed inequities in married women’s property rights. In Pennsylvania, for example, lawmakers passed the Married Women’s Property Act of 1848, stipulating that wives owned personal property they brought into a marriage and received afterwards, such as rents on their real estate. They could also independently write wills. The law did not give a married woman freedom to sell her real estate without the husband’s permission but confirmed that he needed her consent before he attempted a sale. Women’s rights reformers considered the 1848 Pennsylvania law a positive step, but they protested in 1855 when the legislature rejected the right of wives to control their earnings. The lawmakers reversed this decision in 1872 but still required women to file in local court their intentions to keep their separate wages. Through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, legislatures and courts wrestled over women’s economic rights versus the ideology of marital unity, gradually granting women more autonomy through piecemeal reforms.

Gaining the right to vote required much energy and resilience before ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Lucretia Mott served as president of the American Equal Rights Association, which formed in 1866 but split three years later over the issue of whether Black men should receive the vote before all women. The American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) supported the Fifteenth Amendment extending the vote to Black men (ratified in 1870), while the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) opposed its approval without the franchise for women. The New Jersey Woman Suffrage Association, established in Vineland in 1867, and the Pennsylvania Woman Suffrage Association, founded in Philadelphia in 1869, allied with AWSA. After Congress rejected an amendment for woman suffrage in 1887, the NWSA and AWSA united in 1890 to form the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), which crusaded with other societies for women’s vote at the state and local levels.

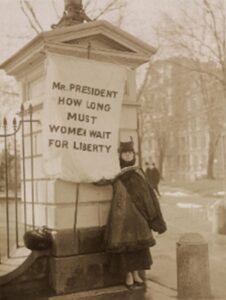

Referenda in 1915 for woman suffrage in Pennsylvania and New Jersey failed, while Delaware offered the vote only to women taxpayers in school elections. The suffragist Alice Paul (1885-1977), of Mount Laurel, New Jersey, who earned degrees at Swarthmore College and the University of Pennsylvania, then propelled the movement forward at the national level. With other members of the Congressional Union, Paul adopted strategies from English suffragists, including rallies, parades, and vigils. After Congress passed the woman suffrage amendment on June 4, 1919, Pennsylvania ratified it within the month, but the New Jersey legislature waited until February 1920. Delaware rejected the amendment in 1920 and did not ratify until three years later, even though the Nineteenth Amendment gained the number of states needed for approval by August 1920.

Beyond the Nineteenth Amendment

Although many activists were satisfied with adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment, Alice Paul refused to stop fighting for women’s rights. In opposition to reformers such as Florence Kelley (1859-1932) of Philadelphia, who favored protective legislation for women workers, Paul and other members of the National Woman’s Party in 1923 drafted the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) to incorporate into the U.S. Constitution an unequivocal statement of equal rights regardless of sex. They lobbied until 1972, when Congress adopted the amendment and sent it to the states for ratification. Although Delaware, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and twenty-seven other states endorsed the ERA within a year, the measure failed ratification by the required three-fourths of states.

Economic change in the greater Philadelphia region from the nineteenth century to the post-World War II era highlighted the need for the ERA and inspired increasing numbers of women to fight for equal rights. In the 1800s, working-class women and girls worked as domestic servants and helped to industrialize the region in textile, garment, and other manufacturing. Despite low wages, women’s earnings outside the home or from hosting boarders and manufacturing within the household provided essential support for their families. In the early twentieth century, female garment workers participated in strikes to obtain higher incomes and improve conditions. Black working-class women continued to face harsh discrimination in education and business so labored primarily in domestic service, despite growing opportunities for white women in clerical and sales positions. World War II created openings for women in heavy industry and armaments that disappeared when the war ended. As described by Betty Friedan (1921-2006) in her influential The Feminine Mystique (1963), American culture in the 1950s idealized middle-class households with male breadwinners and dependent wives and children. Nevertheless, increasing educational opportunities and role models of individual women who broke through severe barriers in the professions and business inspired young women to challenge inequality and stereotypes.

In the 1960s and 1970s, women’s rights advocates acted on many fronts to secure the powers and self-confidence that nineteenth-century feminists had demanded at Seneca Falls. In 1961, at the urging of Esther Peterson (1906-97), then Assistant Secretary of Labor for Women’s Affairs, President John F. Kennedy (1917-63) established the President’s Commission on the Status of Women (PCSW). Eleanor Roosevelt (1884-1962) chaired the commission, which included among its members Richard A. Lester (1908-97), a Princeton University professor, as vice-chairman, and Caroline F. Ware (1899-1990), a historian who had taught at the Bryn Mawr Summer School for Women Workers. The commission promoted the right of women in all states to own businesses and property, control their own earnings, and serve on juries; its recommendations resulted in an executive order mandating equal job opportunity for women in federal contracts and the Equal Pay Act of 1963. Through the commission’s “Consultation on Negro Women,” Black professional women advised the PCSW to consider the impact of racism on Black families and women. The consultation made recommendations, such as raising the minimum wage and promoting unions for domestic and other service workers, that the PCSW failed to prioritize. Subsequently, Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 provided a platform for gender equity, though the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) refused initially to hear sex discrimination cases.

National Organization for Women

Philadelphia area women joined the National Organization for Women (NOW), which formed in 1966 to push the EEOC to fulfill its responsibilities under Title VII, then quickly added to its platform the ERA, reproductive rights, child care, and other goals. Ernesta Ballard (1920-2005), who served on the national NOW board, in 1968 organized local women to establish Philadelphia NOW. The Pennsylvania NOW started in 1971, assembling in 1973 in Philadelphia its first convention of state chapters. The Philadelphia chapter published the Philadelphia NOW Newsletter and worked toward a range of goals including ratification of the national ERA; adding an ERA to the Pennsylvania state constitution; ending sex discrimination in employment, politics, education, and public accommodations; repealing Pennsylvania’s restrictive abortion law; establishing government-funded child care; and improving women’s image in the media.

In 1968, the group New York Radical Women rallied feminists from New York, New Jersey, and elsewhere to demonstrate at the Miss America pageant in Atlantic City, New Jersey. They threw what they called “instruments of female torture” such as girdles, bras, hair curlers, and Playboy magazines into a “freedom trash can,” gaining national publicity that helped to ignite the feminist movement in many cities. Philadelphia-area women in 1968 started consciousness-raising groups in which they gained motivation for collective action through discussions of how inequality and sexism affected their individual lives.

On August 26, 1970, Philadelphia NOW, the Women’s Liberation Center, and more than twenty other organizations celebrated Women’s Equality Day on the fiftieth anniversary of the woman suffrage amendment. In Rittenhouse Square, thousands of women and men heard speeches and talked to representatives of Philadelphia NOW, the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom, Women United for Abortion Action, and other feminist groups. Media coverage energized the movement, leading to the growth of consciousness-raising groups throughout the region. The Women’s Liberation Center provided meeting space and networking opportunities in Philadelphia for radical feminist groups that women started in response to their subordination in male-dominated organizations.

National Black Feminist Organization

While Black women helped to organize NOW, by 1973 feminists in New York City, including Florynce Kennedy (1916-2000) and Margaret Sloan-Hunter (1947-2004), became convinced that a new organization, the National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO), was needed to address the challenges facing working-class women of diverse ethnic backgrounds. The NBFO established chapters in cities across the U.S., including Philadelphia in 1975. Members of Philadelphia NOW and radical feminist groups collaborated to provide social services to women in the Philadelphia region, including literature and advice for finding jobs and health care, fighting sex discrimination, dealing with rape and sexual abuse, and transitioning through separation and divorce. Philadelphia feminists took the lead, building on the work of nineteenth-century reformers, in creating women-led agencies such as the Elizabeth Blackwell Health Center for Women, Women Organized Against Rape, Women’s Law Project, and Pennsylvania Program for Women and Girl Offenders. In 1976, these and other agencies created Women’s Way, the first coalition to raise funds for feminist social service organizations in the United States.

By the early 2020s, a century after ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment for woman suffrage, the status of women remained mixed. While many women in the greater Philadelphia region had gained leadership in the arts, media, community service, healthcare, education, and business, and despite the important support of male allies, few women had reached high political office. No women had been elected to the U.S. Senate from New Jersey, Pennsylvania, or Delaware. In the U.S. House of Representatives, in 2023, Lisa Blunt Rochester (b. 1962– ) held the at-large seat for Delaware and four women represented districts in southeastern Pennsylvania, but none represented southern New Jersey. Pennsylvania has had no woman governor since the colonial period, while Delaware and New Jersey have each had one. The U.S. Supreme Court’s reversal of Roe v. Wade (1973) in June 2022 highlighted the necessity of political power for achieving and protecting women’s rights. Movements such as Black Lives Matter and #MeToo, and lack of a national ERA, demonstrated how much change remained necessary.

Jean R. Soderlund, Professor of History emeritus at Lehigh University, is the author of Quakers and Slavery: A Divided Spirit (1985) and Lenape Country: Delaware Valley Society before William Penn (2015), for which she won the 2016 Philip S. Klein Book Prize from the Pennsylvania Historical Association. Her latest book, Separate Paths: Lenapes and Colonists in West New Jersey, was published in 2022 by Rutgers University Press. (Information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2024, Rutgers University.