Coal

Essay

In the nineteenth century, Philadelphia banks and entrepreneurs played a pivotal role in facilitating the emergence of coal as the nation’s principal energy source for industry, transportation, and heating, by creating and financing the firms that first brought to market anthracite coal, mined exclusively in rugged eastern Pennsylvania.

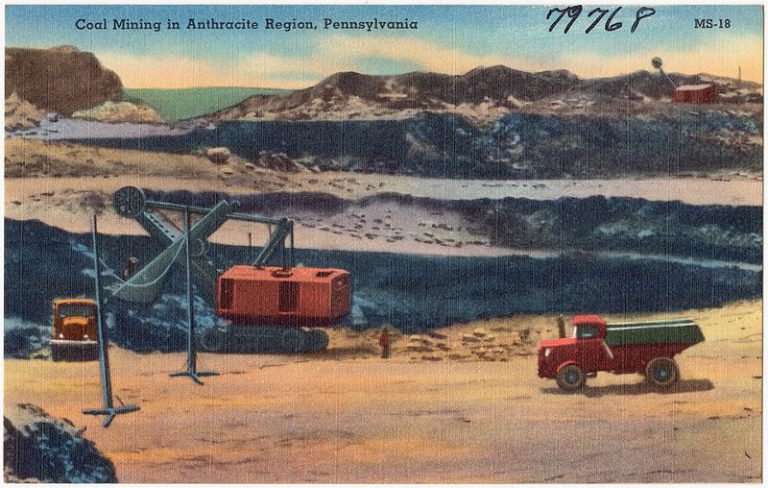

To mine anthracite, or “hard coal,” on a large scale required extensive access to capital, much of which was drawn from Philadelphia. Before the Civil War, transportation firms led the way. The Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company, founded in 1822 by Josiah White (1781-1850) and Erskine Hazard (1789-1865), by 1840 had constructed thirty-six miles of canal, joining ten miles of navigable river down the Lehigh River to Philadelphia. In 1825, investors led by Philadelphia bankers and merchants founded the Schuylkill Navigation Company, which by the 1840s boasted a transportation network of 108 miles of canal and passable river, along with 450 tunnels and 120 locks for a capitalization of $2.2 million, all fed by annual coal shipments of 500,000 tons. In 1828 the North Branch Canal opened, reaching all the way to Nanticoke, and in 1831 it was extended to Pittston, connecting Luzerne County to the Philadelphia market. In 1829 the northern field opened to the New York market with the completion of the Delaware & Hudson Canal, which equaled the Erie Canal in capital outlay. This transportation artery included an inclined-plane railroad and a 110-lock canal system linking Honesdale, Pennsylvania, to Rondout, New York, on the Hudson.

The emergence of the railroad system connecting Philadelphia and other eastern cities to the anthracite region soon eclipsed canal building. Frederick List (1789-1846), a leading early-nineteenth-century German economist and political refugee in Philadelphia in the 1820s, purchased a mine in the Little Schuylkill Valley in Tamaqua and recruited one of the nation’s richest men, Stephen Girard (1750-1831) of Philadelphia, as an investor to develop railroad links connecting mines to market. The railroad eventually became the powerful Philadelphia & Reading Railroad, which opened in 1833. Philadelphian Henry Charles Carey (1793-1879), the leading American economist of the nineteenth century and a close adviser to Abraham Lincoln, and like List an advocate of protective tariffs, also held anthracite mining interests. The Lehigh Valley Railroad (LVRR) opened in 1855 connecting Mauch Chunk (now Jim Thorpe) to Easton and then north through the Wyoming Valley into New York state and east into New Jersey and New York City. To the north, George Scranton’s Delaware, Lackawanna, & Western Railroad opened up the Northern Field to New York City and, via the Erie Canal, the Great Lakes. Everywhere railroads used their control of access to the market as leverage to dominate coal production.

Anthracite Boosts Steel Production

Railroads tied together the critical ingredients of the industrial economy of the nineteenth century: coal, iron, and steel. Once accessed, anthracite coal began to play an indispensable role in the industrial revolution. Prior to the use of anthracite in the smelting of iron, American industry lagged far behind its British counterpart, continuing to use charcoal through the 1830s that resulted in an inferior product unsuitable for rail manufacture. The intense heat unleashed in the burning of anthracite closed the gap. By the 1850s anthracite was fueling half of all iron production in the United States, much of it destined for rail building, much of the rest bound for the emerging field of metal machine making, an important industry in Greater Philadelphia. The city’s central entrepôt for the coal was the Reading Railroad’s massive Port Richmond Terminal, a sprawling complex of twenty-one wharfs on the Delaware River capable of loading scores of vessels. From here coal was shipped up and down the East Coast.

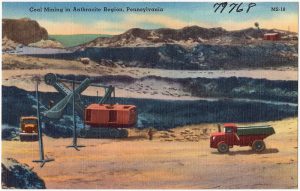

Growing demand before, during, and after the Civil War accelerated anthracite production. Regional coal production went from 910,000 tons in 1840 to 3,700,000 tons in 1850, to 9,200,000 tons in 1860, to 11,000,000 in 1865. Over the corresponding period, value of output increased from $1.3 million to $5.5 million in 1850, to $14 million in 1860, to $65 million in 1865, the final statistic suggestive of the enormous inflation and profits gained as a result of the Civil War. The anthracite region’s population—comprising Luzerne, Northumberland, Schuylkill, and what would become Carbon and Lackawanna Counties—grew rapidly, from 46,790 in 1820, to 66,256 in 1830, to 93,086 in 1840, to 155,743 in 1850, and to 248,655 in 1860. As the basis of the regional economy, mine employment went from 3,000 in 1840, to 10,000 in 1850, to 27,000 in 1860, to 39,000 in 1865. From the Civil War until 1900, anthracite production increased fivefold, from 10 million tons to 60 million tons annually. Tens of thousands of immigrants poured into the region, arriving first from Wales, England, and Scotland, then from Ireland, and finally Poland, Italy, Lithuania, Slovakia, Ukraine, Hungary, and many other lands. Workers unionized in bitter struggle against the mine owners in the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) by the first decade of the twentieth century.

In the late nineteenth century coke processed from bituminous coal began to displace anthracite coal for industrial use, especially in steel production. Drawn from the nation’s vast deposits stretching from western Pennsylvania and West Virginia through Illinois, bituminous, or “soft coal,” was considerably cheaper to extract than anthracite coal. The coking industry developed first in western Pennsylvania, and with it the center of the American iron industry shifted from eastern Pennsylvania to the Pittsburgh region, eventually following the development of the iron mining industry in the Lake Superior region to the major cities of the Great Lakes. By 1905, the Pittsburgh area was producing 18 million tons of coke per year. Bituminous production in Pennsylvania alone reached 80 million tons by the turn of the century.

Oil Displaces Anthracite

Another development from western Pennsylvania in the late nineteenth century ultimately contributed to the displacement of anthracite for home heating use, a long decline that accelerated after World War II. This was the discovery of consumer and industrial uses for oil and then natural gas. An industry dominated by John D. Rockefeller (1839-1937), oil was first shipped to Philadelphia via the Philadelphia and Erie Railroad, connecting with the Reading in Harrisburg. Beginning in the late nineteenth century oil and natural gas were shipped to refineries via pipelines from northwestern Pennsylvania. With the development of the internal combustion engine in the late nineteenth century, petroleum began to displace both coke and anthracite in industrial production.

The Susquehanna River, whose canals provided the original mode of transportation of anthracite to Philadelphia, contributed to the ultimate decline of the anthracite coal industry. The completion of the Holtwood Dam on the lower Susquehanna in 1910 greatly increased the market for electricity consumption in Philadelphia and Baltimore. The introduction of electricity in industrial production allowed for the rapid development of light industry dependent upon small machines, as well as the development of continuous production methods like the assembly line. By 1930 electricity had become the leading energy source in American industry, and most Philadelphia homes had abandoned carbon-burning appliances. In the years after World War II, the burning of coal as a home heating source declined.

Coal nonetheless continued to play an important role in the production of electricity in the region for many decades. Coal-powered plants generated substantial environmental pollution, and according to 2010 research carried out by the nonprofit Clean Air Task Force investigating the remaining Pennsylvania and New Jersey power plants using coal for generation, fine particle air contamination consisting of soot, heavy metals, sulfur dioxide, and nitrogen oxides was associated with dozens of deaths. Most of these plants were slated to close by the end of 2015.

From the beginning, coal contributed to workplace and environmental problems. Tens of thousands of Pennsylvania workers died in the state’s mines, and tens of thousands more suffered and died from coal workers’ pneumoconiosis, or black lung. The rivers and soils near mines and beehive coke ovens were damaged. Air pollution, coal ash deposits, and one ongoing underground coal fire, at Centralia, Pennsylvania, continued to present environmental problems to the state into the twenty-first century. One of the prices of coal, despite its central role in boosting area industry, has been these long-term effects.

Thomas Mackaman is Assistant Professor of History, at King’s College, Wilkes-Barre. He is author of the forthcoming book, New Immigrants and American Industry, 1914-1924. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

Links

- Coal Discovery (Explore PA History)

- Coke Ovens [Steel] Historical Marker (Explore PA History)

- Mining Anthracite (Explore PA History)

- Remembering The Pride And Pain Of Pa. Coal Mines A Shenandoah Veteran Points To The Many Who Died Young. A Memorial, He Says, Is Long Overdue. (Philladelphia Inquirer, August 7, 1994)

- Room and Pillar Mining (YouTube, May 29, 2011)