Consolidation Act of 1854

By Andrew Heath | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

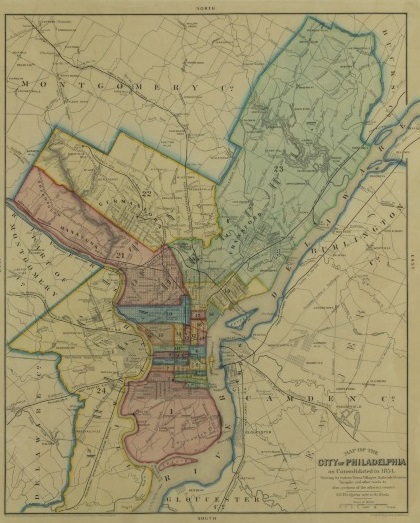

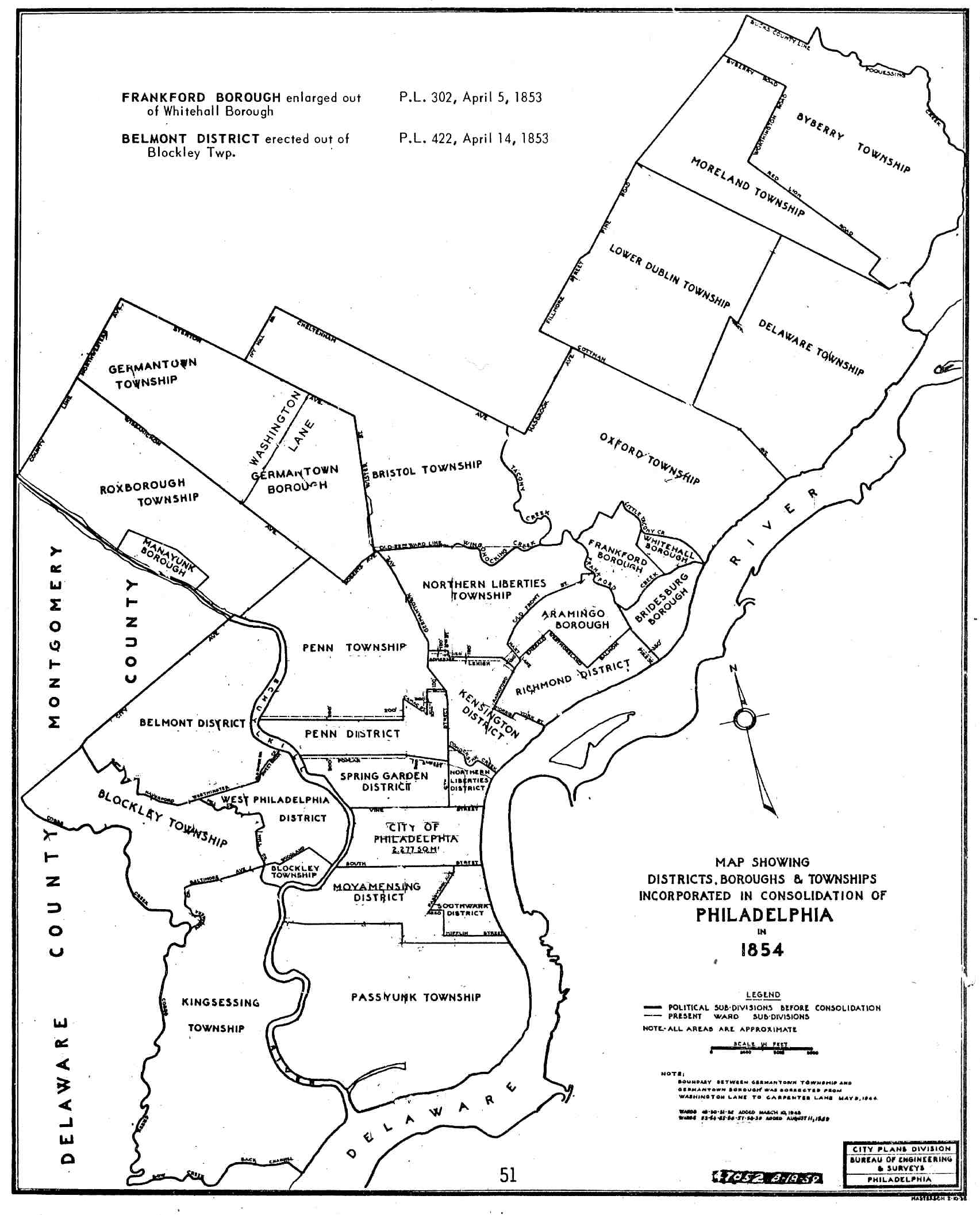

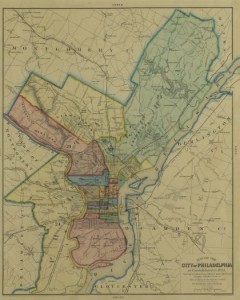

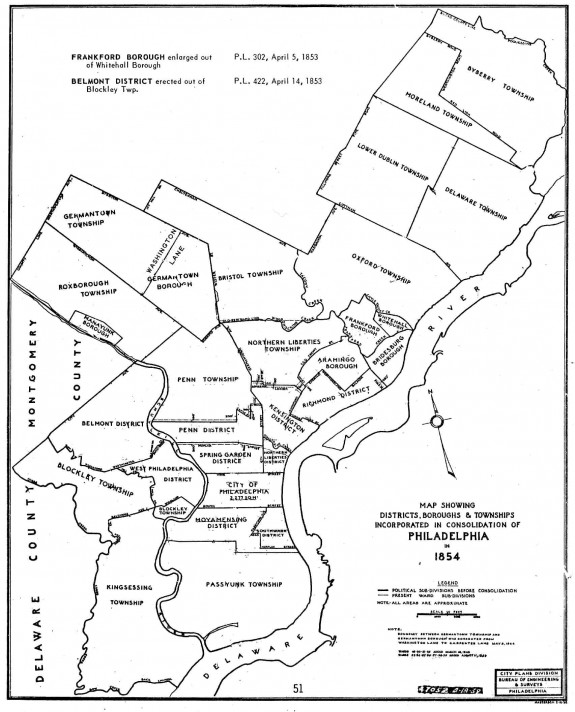

The Consolidation Act of 1854 extended Philadelphia’s territory from the two-square-mile “city proper” founded by William Penn to nearly 130 square miles, making the municipal borders coterminous with Philadelphia County and turning the metropolis into the largest in extent in the nation, a position it held until Chicago leapt ahead in 1889. Consolidation’s supporters believed the measure would enable municipal authorities to deal with the epidemics of riot and disease that ravaged the city in the 1830s and 1840s, while giving them the power and dignity to challenge for metropolitan supremacy. Although the bid to overtake New York as the first city failed, the 1854 act led to some impressive civic achievements. Since its passage, the city’s boundaries have barely changed, and despite charter revisions in 1887 and 1951, contemporary Philadelphia still bears the imprint of the mid nineteenth-century measure.

Until 1854, Philadelphia’s population concentrated within the original city boundaries set by William Penn (1644-1718), between the Delaware and Schuylkill rivers and from what is now South Street to Vine. By 1820, however, inhabitants in the independent boroughs, districts, and townships that made up the rest of the county already outnumbered those in the city proper. Some of these suburbs were places of significance in their own right, with Spring Garden, the Northern Liberties, and Kensington, all north of the city center, ranking as the ninth, eleventh, and twelfth biggest urban settlements in the nation in the 1850 census. These districts, in common with their neighbors, had won from the Commonwealth the right to establish their own local governments, with powers to tax, borrow, and spend, and thus remained independent of Philadelphia City’s control. While they varied in their social and political character, they tended to be poorer and more Democratic than the historic center, which they sometimes referred to as the “Whig Gibraltar.”

The first organized calls for uniting the built-up portions of the county under one municipal authority came in response to two major riots in 1844. The anti-Catholic violence, which broke out in the northern suburb of Kensington and the southern district of Southwark–both neighborhoods in which Irish immigrants and native-born Protestants lived in close proximity–exposed the inadequacy of the prevailing system of law enforcement. With no uniformed officers in the county, and every jurisdiction responsible for its own policing, there was little to prevent violence from escalating. It took state militia armed with cannon to suppress the Southwark disturbance. Soon after the riots, the Public Ledger called for annexing the built-up outlying districts, and in November, citizens gathered at the County Court House (Congress Hall) to make the case for enlarging the city boundaries.

Opposition to a New Charter

The move for a new charter over the winter of 1844-5, however, came to very little. A bill was drawn up for consideration by the Commonwealth–which then, as now, held the power to create, alter, and destroy local government–but influential owners of property and city debt like Horace Binney (1780-1875) organized to oppose the proposal. Critics feared that consolidation would hand the keys of the Whig city to suburban Democrats, and that real estate owners in the prosperous city proper would be taxed to pay the interest on loans taken out by indebted outlying districts, which needed to borrow to maintain their rapid growth. The opponents of consolidation lobbied for legislation that would maintain the districts’ independence yet still address the issue of civil disorder by requiring that all built-up portions of Philadelphia retain one policeman for every 150 taxable inhabitants.

This measure failed to prevent another major riot in 1849, which sparked renewed calls for annexation. While this time the proposal enjoyed more support from the city’s merchants, manufacturers, and professionals, it failed once again in the state capital. Instead of consolidation, Harrisburg legislators established a police force under an elected marshal to deal with disorder across the built-up sections of the metropolis. The Marshal’s Police proved relatively successful in maintaining the peace, and despite endemic fighting among rival companies of volunteer firemen and street gangs, there were no major riots from 1850 to the eventual passage of the Consolidation Act in 1854.

Calls for metropolitan union nevertheless grew louder, despite the relative calm of the early 1850s. By then, municipal reformers hoped to do more than inoculate the city against the violence of the preceding decades. Many saw the district system as unnecessarily costly, as dozens of jurisdictions duplicated services that could have been provided more efficiently by a single government. Others feared that the city proper might become “an appendage to her own colonies,” as growth in industrial districts like Spring Garden and Kensington outpaced the historic center. Some no longer saw those suburbs as a financial burden, but rather as a potential source of tax revenue, because heavy investment in the Pennsylvania Railroad after its chartering in 1846 had left the city proper far more heavily indebted than its neighbors. Real estate owners in central Philadelphia complained that suburban property holders benefited from the trade that resulted from the rail link to Pittsburgh but had contributed little in the way of public funds to the railroad’s construction.

Rivalry With New York

Perhaps most importantly, though, supporters of consolidation believed that only a united Philadelphia would have the power and status to overtake New York in the struggle for metropolitan supremacy, a race the city had languished in for at least three decades as the completion of the Erie Canal (1825) and Chestnut Street’s decline as a financial center after the attack on the Second Bank of the United States by Andrew Jackson (1767-1845) enabled Manhattan to pull ahead. As North and South clashed over the question of slavery extension, advocates of annexation for Philadelphia readily adopted the rallying cry “In Union There Is Strength” for their own cause.

In the early 1850s both of the dominant political parties, the Whigs and the Democrats, promised to back annexation, but in Harrisburg, proposals for charter revision went nowhere. To break the impasse supporters of the measure–prodded by their erstwhile opponent Binney–decided in 1853 to nominate their own slate of candidates for the Pennsylvania Assembly and Senate. In alliance with advocates of a professional fire department, they put forward a mixture of independents and regular Whig and Democratic party nominees. At the head of the ticket was Eli Kirk Price (1797-1884), a progressive real estate attorney, while the wealthy locomotive builder Matthias W. Baldwin (1795-1866) was among the candidates for the lower house. Most of the consolidation slate triumphed, and before Price went off to take his seat in the Senate, an Executive Consolidation Committee met in Philadelphia to draft a bill.

The Executive Consolidation Committee that convened in the Board of Trade rooms at the Merchants’ Exchange over the winter of 1853-54 represented a cross-section of Philadelphia’s economic elite. Many owned substantial real estate beyond the historic corporate boundaries, and by proposing to annex the entire county rather than just the much smaller built-up environs of the city proper, they went much further than their predecessors. Despite murmurs of protest from rural districts, the charter passed both houses and was signed into law in February. The new metropolis, encompassing industrial suburbs, romantic rural retreats, and vast stretches of farmland, came into being four months later.

Architects of the 1854 charter saw it as a victory over the self-interested politicians of the district system and the triumph of a rational, modern government over an antiquated predecessor. Executive power was invested in a mayor elected at-large for a two-year term, and voters chose the nativist playwright Robert T. Conrad (1810-1858) as the first to hold the office. In place of the old boundaries on the county map, meanwhile, twenty-four wards sent representatives to the Common and Select Councils. Ward representation preserved an element of localism in the councils–something party politicians quickly learned to exploit–but the financial muscle and territorial reach of the enlarged city enabled urban planning on a far greater scale than previously had been possible.

Preserving Open Spaces

The Consolidation Act resulted in other important changes for newly expanded Philadelphia. Among them, the legislation gave municipal authorities the duty to preserve open spaces, and before and after the Civil War steps were taken towards creating Fairmount Park, which lay entirely beyond the boundaries of the old city proper. Standardized street names and numbers (1857), a professionalized the fire department (1871), and a new city hall at Broad and Market Streets (1871-1901) demonstrated civic authorities’ readiness to raise the city’s metropolitan status, as did the suburban expansion fueled by horse-drawn streetcar lines and other infrastructure improvements that opened up cheap land in the consolidated city for builders. When Philadelphians in the second half of the nineteenth century contrasted their city of row homes with the tenements of New York, they credited the city’s expansion with eliminating the need for “vertical slums.”

Perhaps most importantly, though, consolidation gave the municipal government the power to maintain the peace. While violence did occasionally break out–in 1871, for instance, the African American civil rights campaigner Octavius Catto (1839-1871) was shot dead on a turbulent election day–the mayor, with his control of a large, uniformed police force, always had the resources at his disposal to prevent the kind of conflagrations that threatened to engulf the city in 1844. Under Republican stewardship, Philadelphia avoided the draft riots that occurred in New York in 1863 and the worst of the conflict between railroads and workers in the Great Strike of 1877. Citizens credited the Consolidation Act for the relative peace in a city once notorious for disorder.

Some of these developments, however, owed more to legislation in Harrisburg than they did to actions by the city government, and by the late 1860s, the habit of state officials overriding the municipal authorities in matters pertaining to the metropolis caused frequent complaints. So too did the tendency of councilmen to claim executive power for themselves, thus weakening the powers of the mayor’s office, which consolidators had sought to strengthen. As party bosses–usually Democratic in the immigrant enclaves of South Philadelphia, but Republican in the growing suburbs–established ward strongholds, centralized city- and state-wide Republican machines distributed jobs and contracts to supporters. After the Civil War a generation of affluent reformers began to see the 1854 act more as a giant source of patronage than a measure designed to bring peace, prosperity, and economic government. They hoped another new charter, eventually passed in 1887, would improve matters, but under Republican leadership, Philadelphians remained, in Lincoln Steffens‘ memorable phrase, “the most corrupt and the most contented.” This was consolidation’s unanticipated legacy, but the act’s limitations should not mask its real achievements in laying the foundations of modern Philadelphia.

Andrew Heath is a Lecturer in American History at the University of Sheffield, U.K. He is currently writing a book on the Consolidation of 1854. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History