Crosstown Expressway

Essay

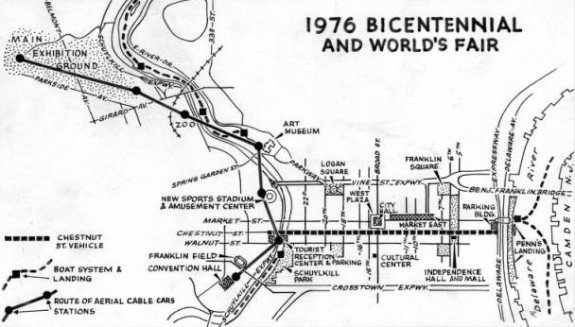

The Crosstown Expressway, a proposed limited-access highway on the southern edge of Center City, became the subject of prolonged controversy during the 1960s and 1970s as redevelopment schemes met with neighborhood resistance. The envisioned highway first appeared in redevelopment plans for Center City during the 1940s and came to play a role in regional traffic planning. However, the most significant aspect of the expressway’s history was its defeat by popular protest by 1974.

Under the direction of Philadelphia planning director Edmund Bacon (1910–2005), the route of the Crosstown Expressway figured prominently in the 1947 Better Philadelphia Exhibition, where it marked the boundary of Center City redevelopment. Bacon contended that the artery would reduce traffic on city streets–a prerequisite for successful redevelopment of Center City, particularly Society Hill. A swath of land running from the Schuylkill to the Delaware Rivers along South Street was found to be “blighted” and ripe for demolition, providing space for a such a major traffic artery. In promoting the necessity of urban redevelopment, the Better Philadelphia Exhibition was closely tied to the political agenda of the emerging reform movement. When reform-mayor Joseph Clark (1901-90) came to power in 1951, the Crosstown became integral to plans to redevelop Center City.

In 1955, the city’s Urban Traffic and Transportation Board officially proposed a limited-access highway. It reasoned that the Crosstown Expressway would enhance the functioning of the regional freeway network as the southern segment of an inner loop connecting the Schuylkill Expressway and Delaware Expressway (I-95). For the same reasons the Greater Philadelphia Movement, a coalition of civic organization leaders, pressed to include the envisioned Crosstown in the Interstate system in 1957. Further planning was to be coordinated with the neighboring counties, a responsibility later assumed by the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission.

By 1963, the proposed Crosstown Expressway became the focus of public debate. Citizens’ groups, most notably the Queen Village Neighbors Association, complained that the prospect of a highway was thwarting efforts to revive the neighborhood. Additionally, critics objected to dividing South Philadelphia from Center City and organizations such as the Philadelphia Housing Association and United Neighbors Association raised concerns about the relocation of residents. Confronted with these objections, planning for the expressway stalled.

Appraisals Trigger Further Resistance

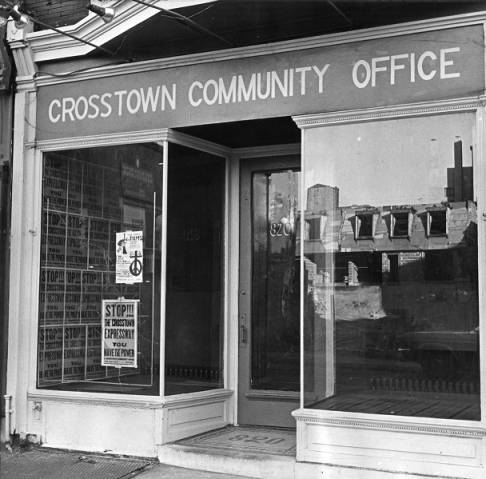

Consequently, it came as a surprise to many when the Pennsylvania Department of Highways began conducting appraisals to acquire property along South Street early in 1967. A public meeting organized by the Hawthorne Community Council and the Society Hill Civic Association condemned the department’s action as lacking adequate provisions for relocation. A group led by Hawthorne activist Alice Lipscomb (c.1916-2003), George Dukes (1931-2008) of the Rittenhouse Community Council, and lawyer Robert Sugarman (c.1938-2008) of Society Hill formed the Citizens’ Committee to Preserve and Develop the Crosstown Community (CCPDCC). In response to the emerging opposition, Mayor James Tate (1910-83) publicly criticized the Department of Highways for starting appraisals and warned that more time was needed to resolve the many problems related to the construction of the expressway. However, he did not question the necessity of the Crosstown.

While the unresolved problem of relocation initially sparked the conflict, the argument that the Crosstown would separate South Philadelphia from Center City increasingly gained attention for its racial implications. Opponents dubbed the Crosstown the “Mason-Dixon Line,” describing it as a mechanism to divide white Philadelphians north of the highway from African Americans to the south. In addition, the CCPDCC began to focus on the issue of deteriorating property in the proposed route and turned toward a new strategy of pushing for renewal in the area as a means to prevent construction of the expressway. In 1968, the CCPDCC formed the Crosstown Development Corporation to elaborate a counterproposal for the South Street area and promote renewal projects as the nucleus of redevelopment in place of the proposed expressway. The citizens committee contracted with architect Denise Scott Brown (b. 1931), who suggested returning South Street to its earlier functions as a commercial strip and hub of adjoining communities. This aim was bolstered by the “South Street Renaissance,” a movement of countercultural entrepreneurs to reinvigorate South Street’s commercial and cultural life.

While the resistance mounted, the expressway retained the support of the Pennsylvania Department of Highways, the Chamber of Commerce, and some members of City Council who viewed a limited-access highway on the southern edge of Center City as essential. Mayor James Tate aimed at reconciliation: He appointed a committee to publicly discuss the issue and mandated a comprehensive traffic study. While the committee attempted unsuccessfully to reach a final decision, both Tate and his successor, Mayor Frank Rizzo (1920-91), failed to take a clear position on the Crosstown.

Meanwhile, Bacon and the City Planning Commission changed their minds. Increasingly, the proposed expressway was seen as an obstacle to expanding the kind of redevelopment that had been successful in adjacent Society Hill. The CCPDCC’s preliminary work helped to convince the City Planning Commission to submit a proposal to the federal Neighborhood Development Program for small-scale redevelopment in the South Street area, similar to Society Hill. Such a project also was incompatible with construction of an interstate highway, so when the federal government funded the redevelopment plan in 1971, it effectively ended prospects for an expressway. The Crosstown Expressway was formally deleted from the plans in 1974.

The Crosstown Expressway was by no means the only controversial proposal that came under attack in the late 1960s and 1970s. However, its defeat marked a turning point in the history of urban planning in Philadelphia. The successful opposition against the expressway became a precedent for the rising resistance against large-scale projects. The opposition’s alternative proposals for the South Street area highlighted the potential of the kind of small-scale neighborhood development that gained support during the 1970s.

Sebastian Haumann is Assistant Professor of History at Darmstadt University of Technology in Darmstadt, Germany. In his dissertation he compared protest movements against urban redevelopment in Philadelphia and Cologne. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University