Delaware River Basin Commission

Essay

The four-state compact that established the Delaware River Basin Commission was a breakthrough innovation in addressing the interrelated land and water impacts of natural resources spanning political jurisdictions. For the first time, the federal government and several states joined as equal partners in a single agency to regulate and develop the watershed of an entire river basin. Following its inception in 1961, the DRBC made significant progress toward meeting the environmental and political challenges that led to its founding, even as it grappled with emerging issues created by population growth, new technologies, and ecological change. In the process, it straddled the longstanding polarity between resource conservation, which allowed measured use, and preservation of natural resources in an untouched state.

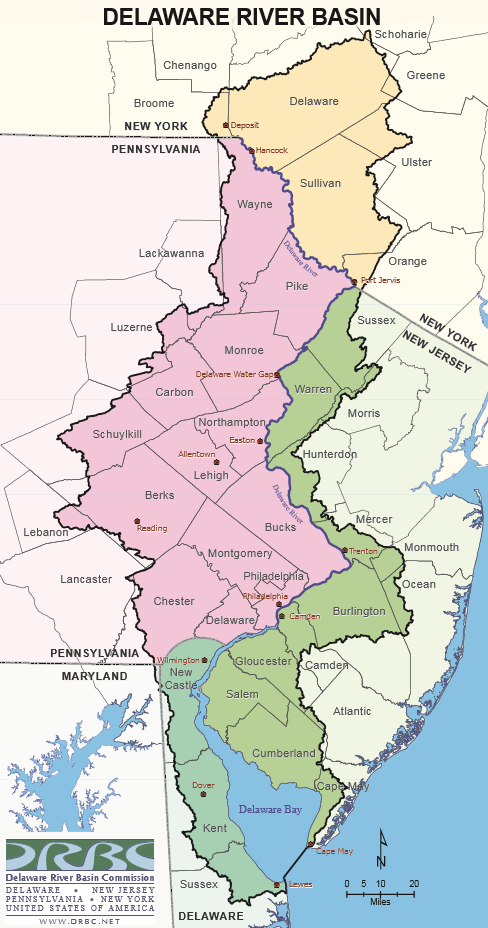

The Delaware River is a key regional water resource spanning the boundaries of four states in the northeastern United States: Delaware, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania. Established October 27, 1961, through concurrent legislation ratified by the four basin states and the federal government, the DRBC was formed to address the often contentious planning, development, regulatory, and allocation issues posed by the expanse of the Delaware River watershed (the area drained by the river). Among the issues prompting its founding were water supply shortages, pollution of the tidal Delaware in the urbanized stretch below Trenton, New Jersey, and flooding spawned by the hurricanes of 1955. The first such federal-state partnership in the United States, the DRBC subsequently served as a national and international model.

The DRBC oversees the longest undammed river in the United States east of the Mississippi; the Delaware flows 330 miles from Hancock, in upstate New York, to the mouth of the Delaware Bay. As of 2016, more than thirteen million people (about 4 percent of the nation’s population) relied on the waters of the Delaware River Basin for drinking, agricultural, commercial, and industrial use, although the river drains only 0.4 percent of the nation’s continental land mass. A powerhouse of the regional economy, the basin supported the largest freshwater port in the world along with six hundred thousand jobs generating $10 billion in annual wages, according to a 2011 study.

Interstate wrangling over Delaware River water rights began in earnest as early as the 1920s, driven in large part by the water needs of the region’s two largest cities, New York and Philadelphia. New York City, situated just outside the Delaware Basin, sought to tap Delaware tributaries within New York State to fill its reservoirs, while Philadelphia, within the basin, was counting on the river’s waters to meet its present and future needs. Efforts to reconcile competing demands for water resulted in multiple failed attempts at an interstate compact, as well as litigation before the U.S. Supreme Court, as the three downstream states opposed New York City’s efforts to divert water from the Delaware. Representatives of both New York City and Philadelphia took part in the negotiations that led to the creation of the DRBC.

Fear of Centralization

At the same time, efforts by the federal government to establish national or regional water planning agencies had been rebuffed by states concerned that their water rights might be abridged. During the New Deal, the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt (1882-1945) created a National Resources Planning Board, but Congress quashed it in 1943 for fear of excessive centralization of power. Legislation establishing the DRBC compact was forged during the administration of President John F. Kennedy (1917-63) after months of fine-tuning to craft an agreement that would allow coordinated federal and state action in the river basin, while addressing federal concerns about constitutionality and potential threats to jurisdiction, and protecting state prerogatives in managing water and related land resources within their borders.

The pioneering interjurisdictional compact replaced a patchwork of forty-three state agencies, fourteen interstate agencies, and nineteen federal agencies that an article in the magazine of the American Water Resources Association termed “a regional body with the force of law to oversee a unified approach to managing a river system without regard to political boundaries.” Under the water law doctrine of equitable apportionment, states have the right to a share of river water that originates within or flows through their terrain. Recognizing the need to manage resources throughout the entire Delaware watershed—the area drained by the river—the compact empowered the DRBC to allocate water supply, protect water quality, regulate water withdrawals and discharges, develop water conservation initiatives, create flow management policy, plan for water needs and recreation, and finance capital projects, programs, and operations through bond issuance and cost sharing.

Headquartered in West Trenton, New Jersey, the commission was one of the few basin management agencies to have regulatory, as well as planning and monitoring responsibilities. Key successes included improved water quality, implementation of an effective drought management policy, and comprehensive watershed planning. Much of the river was afforded special protection status, to preserve water quality, and was enrolled in the National Wild and Scenic River System, to maintain its scenic nature.

The commission’s membership, as defined by the compact, consisted of the governor of each of the basin states, plus a presidentially appointed federal representative (in 2016, the North Atlantic Division Engineer of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers). Decisions were to be made by majority vote except for drought declarations or member funding quotas, which required unanimity. The initial term of the compact was one hundred years, renewable for a second century, unless any of the partners gave advance notice of intention to leave.

Tocks Island Dam Project

Along with interstate water rights litigation, a second prime impetus for creation of the DRBC was the planned implementation of the multimillion-dollar Tocks Island Dam project. The dam would have been built on the main stem of the river six miles upstream from New Jersey’s Delaware Water Gap, on the northern tip of an island owned by the State of New Jersey, creating a lake forty miles long and up to 140 feet deep. It was ultimately rendered unbuildable by its scope and cost.

The multistate impacts of flooding spawned by two hurricanes in 1955 had cleared the way for federal involvement in Delaware River water affairs. The Senate directed the Army Corps of Engineers to prepare a comprehensive basin-wide resource management plan, which was funded by Congress as part of a massive public works bill, the Flood Control Act of 1962 (P.L. 87-874).

The plan included the Tocks Island Dam as the centerpiece of a multipurpose reservoir project that had flood control, recreation, and hydropower generating components, initially estimated at a cost of $122.4 million. Almost 250 billion gallons of water were to be stored behind the dam. Another ten dams would have been built on Delaware River tributaries. A recreation area, later enlarged and known as the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, was proposed to develop the recreation opportunities promised by the project.

Project costs began escalating almost as soon as the dam was approved, due to inflation, land acquisition prices, and construction issues. The DRBC was intended to serve as the local sponsor of the project in behalf of the four river states and would have owned most of the water behind the dam. Construction was supposed to start in 1967, with project completion scheduled for 1975, but the schedule was delayed by litigation and design problems.

The dam drew resistance first from residents whose property was taken by eminent domain and then from an environmental movement that steadily gathered force after the first Earth Day in April 1970. The plan foundered amid concerns about stagnant reservoir water, unstable geology, cost overruns, budget cuts due to spending on the Vietnam War, and the enactment of new, more stringent environmental regulations. The DRBC, long a proponent of the dam, in July 1975 voted 3-1 against starting construction, with Pennsylvania the only vote in favor. The federal government representative abstained.

But the dam remained nominally viable as a component of the DRBC Comprehensive Plan, for complex reasons related to land earmarked for the national recreation area, as well as the water supply and flood control issues the dam was supposed to address. Federal legislation to remove the project from the books failed several times during the mid- to late 1970s. It was not until 1992 that Congress formally deauthorized the Tocks Island project.

The Rise of Hydraulic Fracturing

The DRBC’s regulatory responsibilities again placed it in a key regional role in the early twenty-first-century controversy surrounding the practice of hydraulic fracturing, commonly known as fracking, the process of drilling into rock and injecting a pressurized liquid to extract gas or oil. About one-third of the Delaware Basin, in Pennsylvania and New York, overlies the Marcellus Shale formation, which contains rich deposits of natural gas. Concentrated in southwestern and northeastern Pennsylvania, the state’s fracking industry mushroomed, bringing with it revenue and jobs, but also environmental impacts that included noise, concrete well pads, pipelines, wastewater disposal, and deforestation. Faced with the looming expansion of fracking into the Delaware River watershed, the potential construction of gas transport pipeline under the river, and opposition to fracking by compact member states Delaware and New York (the New Jersey legislature and the state’s governor were at odds on the issue), the DRBC in 2010 issued a temporary stay on fracking, pending its enactment of regulations for gas production activities. In 2016, a federal lawsuit filed against the DRBC by landowners in Wayne County, Pennsylvania, who held fracking leases, claimed the agency lacked the power to regulate gas drilling. The suit was joined by three Republican Pennsylvania state senators, who claimed the DRBC had usurped authority already addressed under state regulations.

Born in litigation and political horse-trading, the DRBC more than a half-century after its creation continued to struggle with its mandate of managing an essential natural resource transcending multiple state boundaries. Often a source of technical expertise and mediation in the ongoing process of maintaining adequate water quality and supply throughout the watershed, the DRBC’s interjurisdictional regulatory and administrative powers nevertheless thrust it into the foreground in high-profile regional controversies with multiple constituencies, such as those surrounding Tocks Island and fracking. Despite the intent of those who intended the DRBC as a strong advocate and mediator for the river and its resources, the agency found its powers checked by the complexity of the environmental regulatory system in which it operated, the often conflicting interests of the many public and private stakeholders in the Delaware Basin, and financial constraints stemming from the reluctance of its membership to fully fund its work.

Gail Friedman holds a Master’s Degree in Public History from Temple University. She worked as a community planner for Bucks County, Pennsylvania, from 1999 to 2015. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History