Enterprise Zones and Empowerment Zones

Essay

Introduced in the Philadelphia area and the nation in the early 1980s, the enterprise zone was a new kind of urban policy that emphasized market-based, “supply-side” strategies for tackling urban decline, most notably in the form of tax incentives for business. A variation in the 1990s, the empowerment zone, targeted areas of high poverty and unemployment with a combination of tax incentives for business and a modicum of direct spending. Philadelphia and Camden achieved empowerment zone status in December 1994. Although the region’s elites embraced the tax incentive approach embodied in both programs, its efficacy remained questionable.

Deindustrialization, population loss, and myriad social problems beset Philadelphia and Camden by the 1970s. The situation was compounded by the massive reduction in federal aid as President Ronald Reagan’s fiscal axe fell on the programs that had once shielded urban areas from the full force of economic restructuring that accelerated in the 1970s and 1980s. Conservatives offered enterprise zones as a potential solution to the region’s economic woes.

The enterprise zone concept was initially developed in the late 1970s by a British urban planner, Sir Peter Hall (1932-2014), and the Conservative Party’s chancellor of the exchequer, Geoffrey Howe (1926-2015). Both Hall and Howe considered the urban decay that characterized many British cities the result of a burdensome tax and regulatory environment that frustrated private investment. Enterprise zones were to be designated areas within depressed cities in which government regulation and taxation would be stripped away in an effort to stimulate entrepreneurial activity. These zones were soon introduced by the Conservative government of Margaret Thatcher (1925-2013) during the 1980s.

The enterprise zone idea was brought to the United States by Stuart Butler (b. 1947), who used his post at the Heritage Foundation to promote the concept. Soon it was taken up by congressman and later secretary of the Department of Housing and Urban Development Jack Kemp (1935-2009), a leading light in the tax-cutting cause. But despite growing support for enterprise zones, both in the Reagan administration and in Congress, a substantive enterprise zone bill never reached the president’s desk. However, enterprise zone proponents enjoyed greater success at the state and local level, and by the mid-1990s, over forty states adopted enterprise zone programs, including Pennsylvania.

Enterprise Zones in Philadelphia

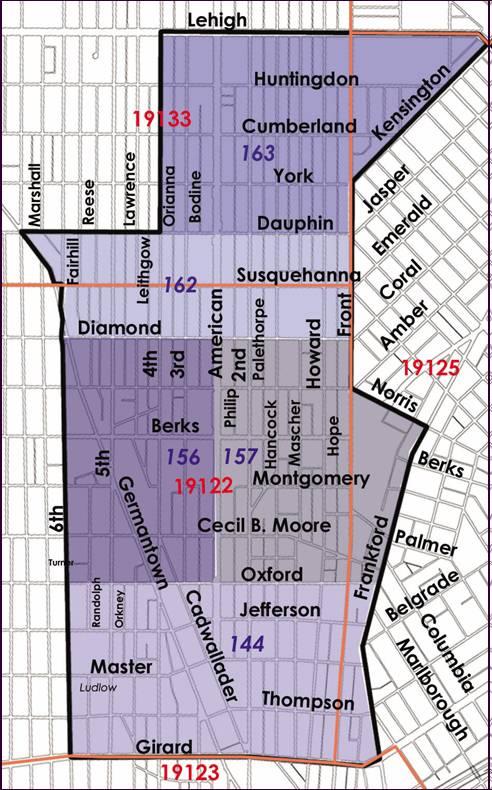

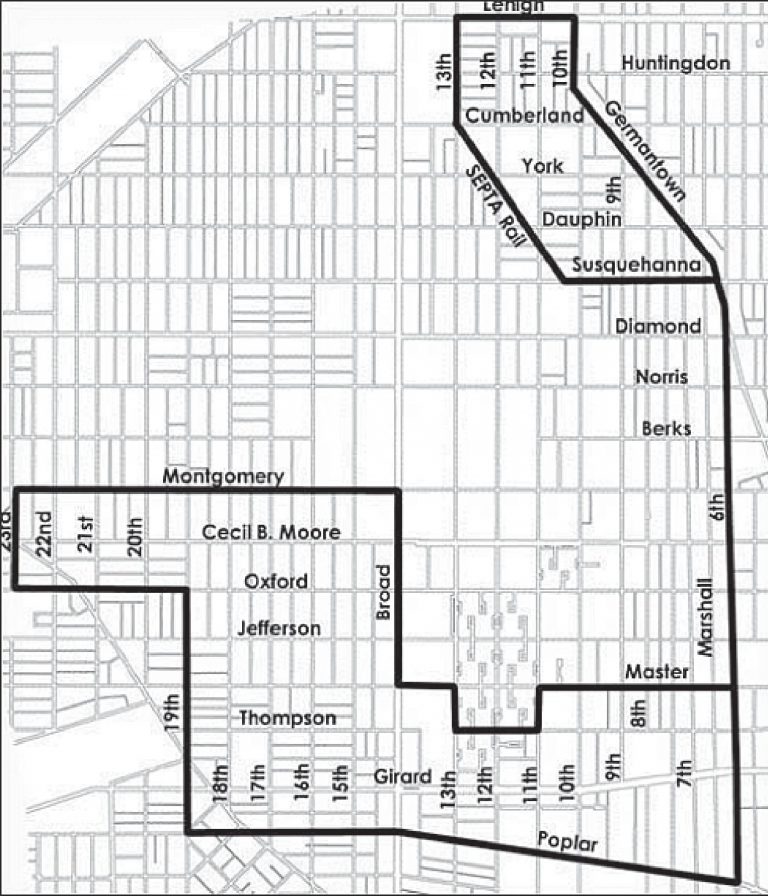

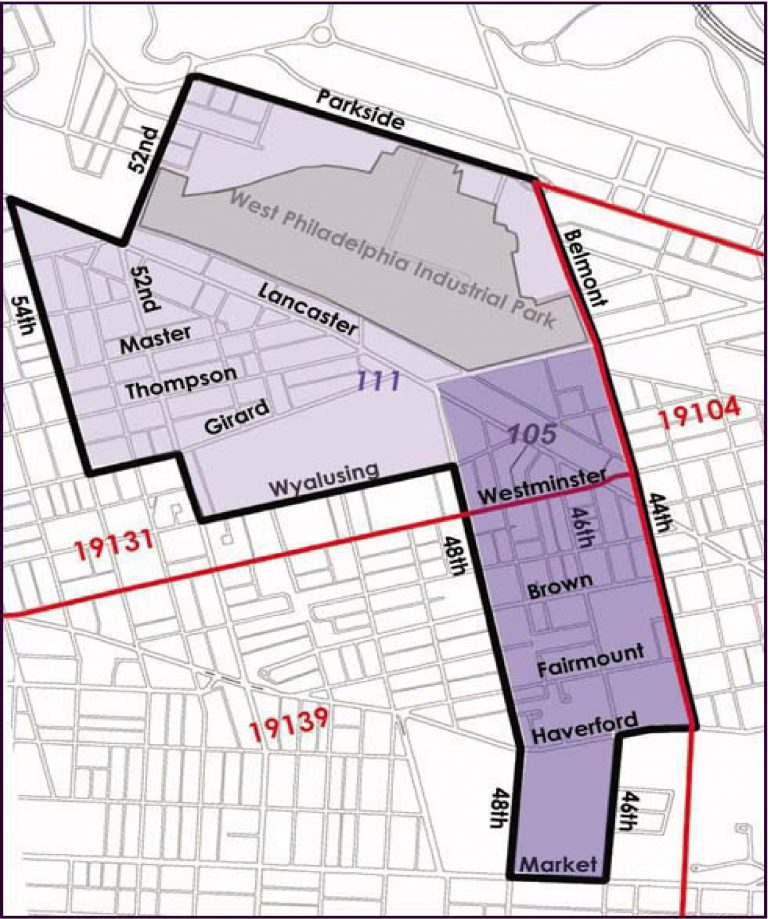

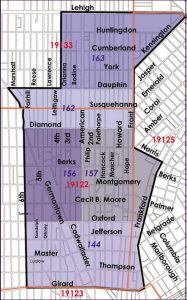

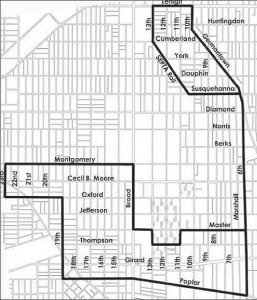

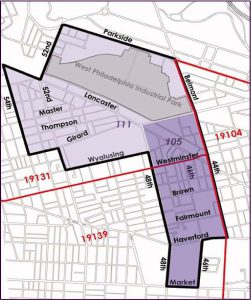

In the early 1980s both the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania under Governor Richard Thornburgh (b. 1932) and the city of Philadelphia during Mayor Bill Green’s (b. 1938) mayoralty, developed urban enterprise zones. In both cases, the politicians acted in anticipation of a federal program that never materialized. Despite muted support for the program, the city established enterprise zones funded jointly by the Philadelphia Commerce Department and the Pennsylvania Department of Community Affairs. The city’s zones offered a variety of incentives, including state tax relief, local real estate tax abatement for individuals and, over time, for businesses, and a rebate program to subsidize the cost of security improvements. Established in 1983, zones were located in three areas: the American Street Corridor, Hunting Park West, West Parkside; the Port of Philadelphia enterprise zone was added in 1989. The selection of these areas was based on need as reflected in high rates of unemployment, capacity to promote economic development, and evidence of a “commitment to the public and private partnership process.”

With the exception of West Parkside, each of these areas had played a key role in Philadelphia’s thriving industrial history and bore witness to its painful decline. Moreover, they had also been targeted by local organizations such as the Philadelphia Industrial and Development Corporation (PIDC) and the Opportunities Industrialization Center (OIC) and federal urban policies such as Model Cities in the 1960s and the Urban Development Action Grant (UDAG) in the 1970s and early 1980s. For example, at the turn of the twentieth century, American Street was the heart of Philadelphia’s textile industry, which employed thousands of workers, in such places as American Knitting Mills, a woolen hosiery manufacturer. However, by the 1960s, the vast majority of textile mills and related concerns had been shuttered. In response, the city, through the PDIC, directed federal funds to American Street in an effort to foster renewed industrial activity. The incentives of the enterprise zone and the empowerment zone were further concentrated on American Street in the 1980s and 1990s.

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, an elite consensus in favor of enterprise zones emerged. The editorial board of the Philadelphia Inquirer made frequent pleas for more investment in the city’s enterprise zones and for the adoption of a federal program. Moreover, all mayoral candidates and U.S. representatives from the Philadelphia area supported enterprise zones in the 1992 elections.

Enterprise Zones Yield to Empowerment Zones

The election of Democrat Bill Clinton (b. 1946) to the White House in 1992 raised hopes of a return to robust investment in the nation’s cities. Many would be disappointed, however, as Clinton rejected a restoration of pre-1980s levels of urban spending. With its ambitious infrastructure program sacrificed in favor of deficit reduction, the Clinton administration’s signature urban policy—the empowerment zone—was a variation on the enterprise zone idea that emerged in the 1980s.

With its emphasis on targeting economically distressed urban areas with a combination of tax incentives for business and new federal spending, the empowerment zone idea drew on the pro-market “neoliberal” enterprise zones promoted by the Reagan administration in the 1980s and echoed in the liberal urban policies of the 1960s and 1970s, such as the Model Cities and the Community Development Block Grant (CDBG) programs. As such, they captured neatly President Clinton’s middle or “third way” political posture.

Despite the mixed record of the enterprise zone, Philadelphia area politicians, led by Mayor Edward G. Rendell (b. 1944), lobbied hard for empowerment zone designation. Their efforts were rewarded in December 1994 when Philadelphia, enhancing its chances by entering a bistate bid with Camden, New Jersey, beat out the competition to win empowerment zone status. Along with tax incentives for businesses, Philadelphia’s empowerment zone areas received a federal grant of $79 million, with $21 million designated for Camden’s zone. Although the two cities combined forces to prepare the bid, they each ran their respective empowerment zones separately. The legislation stipulated that prospective empowerment zones must be located in high-poverty areas.

The Philadelphia empowerment zone consisted of three neighborhoods: North-Central Philadelphia, and in two of the existing enterprise zone areas, West Philadelphia and American Street. The particular location of the zones was driven both by practical assessments of likely success and by political influence. For example, the North-Central census tracts were only added after considerable lobbying by residents and City Council President John Street (b. 1943) who represented the area. Unlike Philadelphia, Camden had a unified zone focused around the downtown. In addition to tax incentives of various kinds, empowerment zone funds were spent on low cost financing for business and community projects, public safety, job training, and housing rehabilitation.

Impact of the Zones

Despite claims from figures such as Mayor Rendell that enterprise zones of the 1980s and early 1990s had “worked,” the empirical evidence suggested a more complex picture. On one hand, the city’s Commerce Department reported that the zones were responsible for the creation of 3,130 jobs and the retention of 11,820 between 1983 and 1992. However, the city failed to account for how many jobs had left during that period, thus raising doubts about the net effect of the zones. Moreover, the city assumed that all jobs retained or created in the zones were the result of the incentives, whereas it was highly likely that some of the jobs would have been retained or created in any case. Finally, there was the question of scale—in light of Philadelphia’s loss of 53,000 industrial jobs during the 1980s alone, the enterprise zone program’s effect was modest at best.

As with the enterprise zones, capturing the net impact of the empowerment zone proved difficult. With respect to Philadelphia, for which the data was more readily available, the city suggested that 460 businesses moved into the empowerment zone between 1995 and 2005 and that the program had created 2,112 jobs for empowerment zone residents. However, it provided no information about whether this was a net growth of jobs. Independent research, conducted by a number of agencies and scholars showed that the empowerment zone program had a rather limited effect on the key measures of unemployment, economic activity, and poverty. As the General Accounting Office (GAO) found, these census zone tracts within the empowerment zone did not significantly outperform census tracts outside the zones that had similar social and economic characteristics. Given the scale of the region’s problems, such results demonstrated major deficiencies in the enterprise zone-empowerment zone approach.

Nevertheless, there were some tangible signs of success. For example, in the American Street corridor, the Crane plumbing warehouse was transformed into an art space and Veyko, a metallurgy company, was attracted to move in with a combination of empowerment zone and PIDC incentives.

Despite these bright spots on the horizon, the empowerment zone program’s small scale limited its potential from the outset. After all, given Philadelphia’s economic difficulties, eighty-four census tracts would have qualified given that they all had poverty rates of 30 percent or higher. Yet, only twelve were granted empowerment zone status. Thus, of the over 300,000 people living in poverty in 1990, only the areas occupied by 20,154 would directly benefit from empowerment zone designation. Hence, even with complete success, the empowerment zone could have had a marginal impact on the city as a whole. As it turned out, the program itself fell short on a range of measures as reflected in the persistence of alarmingly high rates of poverty and unemployment within the areas targeted over the decades by enterprise and empowerment zone initiatives.

Timothy Weaver is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University at Albany, SUNY. He previously held the post of Assistant Professor of Urban Politics at the University of Louisville. He holds a B.A. (Hons.) in Philosophy and Politics from the University of Durham (U.K.) and an M.A. and Ph.D. in Political Science from the University of Pennsylvania. He is author of Blazing the Neoliberal Trail: Urban Political Development in the United States and the United Kingdom (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2016). (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Roxborough and Hunting Park West industrial zones, they are a-changing (WHYY, February 3, 2011)

- End of N.J. urban enterprise zones will 'devastate' cities, lawmaker says (WHYY, August 2, 2016)

- Council supports Keystone Opportunity Zone expansions, called for greater transparency (WHYY, September 15, 2016)

- Proposal would extend the life of five N.J. Urban Enterprise Zones (WHYY, November 23, 2016)

- Plan to extend Urban Enterprise Zone in five cities nears N.J. Senate vote (WHYY, December 16, 2016)