Films (Feature)

Essay

Philadelphia’s association with movie-making dates back to the beginning of the film industry, when the city’s Lubin Manufacturing Company created and distributed many of the first generation of silent films. But after the company’s early collapse, the city never again attained a prominent role in the nation’s filmmaking. After Lubin, Philadelphia served as a setting for telling stories set just outside the national centers of power in New York and Washington, D.C., and far away from Los Angeles, the kind of urban stories that needed local color and a unique backdrop.

The Lubin Manufacturing Company was founded in 1902 by Siegmund “Pop” Lubin (1851-1923), an eyeglasses salesman-cum-industrialist who got his start shooting homemade movies in his backyard. Between 1896 and his film company’s demise in 1916, Lubin produced more than 3,000 movies, but Philadelphia itself did not play a prominent role in his filmography even though the company’s imprint was an image of the Liberty Bell.

After Lubin’s brief reign at the top of the motion picture industry, Philadelphia receded from its prominent position in cinema. The city and its environs continued to make periodic appearances, however, usually playing one of three very particular roles. In the mid-twentieth century, visions of haughty, manner-bound Main Line society dominated depictions of Philadelphia. As deindustrialization began in earnest in the 1970s, attention began to shift to the city itself, especially its rotting manufacturing infrastructure and working-class row house neighborhoods. Subsequently, Philadelphia served either as a distinctive backdrop for a few recurring directors, notably M. Night Shyamalan (b. 1970) and David O. Russell (b.1958), and more often as an archetypal urban area. Philadelphia played that role before, but the frequency of the city’s anonymous appearances greatly expanded with the multimillion-dollar tax credits that the state of Pennsylvania began offering to film studios in 2004.

Glamour

The Main Line dominates depictions of Philadelphia in many mid-century films, which represent the city—or at least its upper crust—as a bastion of old money and rigid, almost European, class distinctions.

The most famous, and highest quality, of these pictures is The Philadelphia Story (1940), which managed to squeeze three of Hollywood’s most indelible stars onto one screen: Katharine Hepburn, Jimmy Stewart, and Cary Grant. The movie is effortlessly classy, the setting all crystalline champagne glasses and book-lined boudoirs. All the action takes place in three estates on the Main Line. There, Hepburn’s heiress, based on real life socialite Helen Hope Montgomery Scott (1904-95), must choose between the affections of three men. The city itself is never seen and is mentioned only in passing when Grant promises to pick up Stewart’s visiting journalist at a train station in North Philadelphia. (This perhaps betrays an ignorance of the city’s transportation geography on the part of the New York-born playwright and the out-of-town screenwriters who adapted his work).

The Philadelphia Story broke box office records and won critical accolades and a few Academy Awards. But Hepburn lost Best Actress to Ginger Rogers, who won for her star turn in another Main Line-focused Philadelphia film. Largely forgotten since, Kitty Foyle, based on a novel by Philadelphia journalist Christopher Morley, tells the story of a working-class girl who dreams of ascending into the city’s ossified elite class. She comes close to succeeding when she falls into a romance with a scion of a prominent banking family, only to be frozen out and nearly destroyed by the massed forces of snobbery and inherited wealth. In her early life, Rogers’ character haunts the Bellevue Stratford Hotel, depicted as the city’s citadel of privilege. Nearly twenty years later, Paul Newman’s The Young Philadelphians (1959) explored similar tropes, again focusing exclusively on the city’s elites depicted as WASP blue bloods obsessed with class distinctions to an almost un-American degree. To drive home the point, the slogan featured on the film’s posters was “When you rip the upper crust off any city, you’ll find raw flesh underneath.”

The Philadelphia Story is much more forgiving of the American aristocracy, depicting Hepburn’s up-by-the-bootstraps fiancé as the heel, not Grant’s absurdly wealthy dilettante. However, depictions of the city’s social hierarchy as stultified and oppressive in Kitty Foyle and The Young Philadelphians proved to have far greater longevity. As the twentieth century wore on, films focusing on the Main Line or Rittenhouse Square set became rarer, although the unflattering depictions of the city’s old school elite as cruel, prejudiced, and capricious appeared again in Tom Hanks and Denzel Washington’s Oscar-winning HIV/AIDS morality film Philadelphia (1993). In a lighter, though similarly damning vein, Eddie Murphy’s comedy Trading Places sends up Philadelphia’s elite. (Dan Aykroyd’s snotty commodities trader is suitably named Louis Winthorpe III.) But that 1983 film unknowingly highlights one of the reasons for the decline of old, glamorous, rigid Philadelphia society: In the 1980s, old money families were being supplanted by those winning fortunes in the newly financialized economy, focused in New York, and leaving little for Philadelphia’s sclerotic stock market.

Grit

Philadelphia’s most indelible cinematic scenes are undoubtedly from the gritty, bleak, and oppressive movies of the 1970s and 1980s. When industrial capital definitively escaped the city in the 1970s, countless abandoned factories and warehouses were left looming over suddenly impoverished working-class neighborhoods. Similar vistas of deindustrialization captured the imaginations of filmmakers in New York and Detroit, but Philadelphia more than held its own in this grim competition.

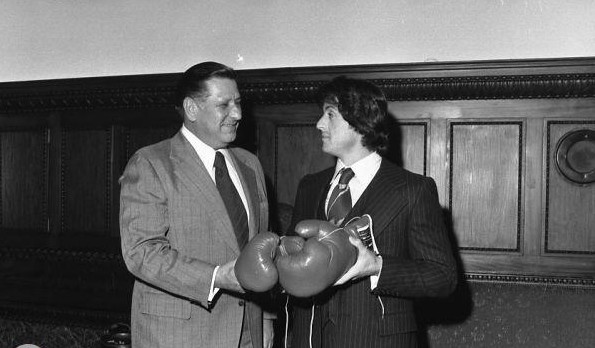

The most famous film of post-industrial grit was, inarguably, 1976’s Rocky. After the parade of cheerier sequels, each seemingly more motivational than the last, it is easy to forget the darkness—literally and figuratively—of the first film starring the “Italian Stallion.” A pall of soot and ash seems to hang over the entire movie, choking Rocky’s row house neighborhood in Kensington. Sylvester Stallone’s (b.1946) iconic character works as an enforcer for a loan shark and is painfully awkward in his interactions with Adrian (who, in turn, works in a shabby little pet store). Everyone seems angry, alienated, and hopelessly stuck in place.

A similar atmosphere pervades the industrial wasteland of David Lynch’s (b.1946) 1977 movie Eraserhead, although here the existential dread and grotesquery is ramped up to an almost unbearable degree. The story, such as it is, focuses on a bizarrely coiffed factory worker, Henry Spencer, who works, lives, and courts women in a space dominated by factories and ex-factories. The movie cannot be properly said to have a narrative, but is instead obsessed with the products of an impoverished, deindustrializing landscape. Factories are still operative in the movie, as mysterious mechanical sounds, clanking and shrilling, adding to the unease of Lynch’s film. Meanwhile the absurd grotesques who populate the landscape are nightmarish caricatures of the characters the filmmaker met while living in an impoverished, violent, dirty corner of the city in the 1960s and 1970s. While Eraserhead (1977) was filmed in Los Angeles a few years after Lynch had moved away from Philadelphia, the vistas of the film are avowedly formed by his experiences in Philadelphia, where he lived in Callowhill and Fairmount, when both of those neighborhoods were more violent and sootier than they became when they subsequently gentrified.

Other classic movies of the era reflected the rising crime wave that threatened to swamp the city, along with much of urban America, and pervasive paranoiac views of authority. In both 1985’s Witness and 1981’s Blow Out, people are murdered horribly in the bathroom of 30th Street Station by figures of supposed law-and-order (a police officer and a government assassin, respectively). When 1995’s 12 Monkeys is not depicting a post-apocalyptic city ruled by animals released from the zoo, it is flashing back to pre-Armageddon days where the city is shown as a dingy and dangerous streetscape scarred by graffiti and abandonment.

Unlike the glitzier Philadelphia films of earlier years, these gritty masterpieces were definitely anchored in the city itself. Although Center City was spotlighted most often, with its array of distinctive landmarks and monuments, these movies also exposed less-seen aspects of Philadelphia. Blow Out even featured a Mummers troupe marching in a Fourth of July parade, while Rocky and, to a lesser extent, Witness showed the old row house blocks that have long housed such a large portion of the city’s poor and working-class residents.

Anonymity

Recent years also witnessed movies set in Philadelphia, or its immediate suburbs, that offered a new window on the city, with neither old money glitz nor postindustrial grime. Silver Linings Playbook (2012) was largely set in white working-class suburbs of Delaware County, including locations in Ridley Park, Upper Darby, Ridley Township, and Lansdowne. There was even a booth in Upper Darby’s Llanerch Diner where Jennifer Lawrence and Bradley Cooper’s characters ate that reported increased trade after the movie’s success. David Russell’s follow-up, American Hustle, focused on the Abscam scandal that took down several prominent Phila-area politicians, but focused on the New Jersey angle instead. M. Night Shyamalan’s movies often took place in the tonier sections of Center City: Rittenhouse Square, Society Hill, Old City, or in the city’s stable northwestern neighborhoods. Like almost all Philadelphia movies, the city’s iconic Center City sights were featured prominently. Neighborhoods like West Philadelphia, Kensington, South Philadelphia, or the Northeast were not featured at all. There were a few exceptions, like 2010’s Night Catches Us, set in 1976 and focusing on an ex-Black Panther’s return to his old neighborhood and the dangers and temptations that awaited him there.

But the city’s distinctive presence in the films of Russell and Shyamalan did not become the norm in the latest era of Philadelphia movies. Instead, the industry increasingly used the city or its environs simply as a stand-in for “Anywhere U.S.A.” That practice dated back at least to 1958 creature feature The Blob, shot in Chester County and Downingtown, but it could have been anywhere. That practice remained the exception, however, until the mid-1980s, with the creation of the Greater Philadelphia Film Office (GPFO). Spearheaded by Sharon Pinkenson, a former wardrobe stylist, the office claimed to have created “$4 billion of economic impact” since its inception, but in the process the city was relegated largely to a secondary film role as backdrop.

Further returns followed Governor Edward Rendell’s (b. 1944) establishment of a $75 million dollar tax credit for filmmakers. In 2009, eleven movies and television shows were shot in Philadelphia resulting in $270 million in direct spending in the region. But few of these movies—Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen (2009), The Best and the Brightest (2010), Shooter (2007), Unstoppable (2010), Paranoia (2013)—actually used the city as a setting, instead using it as a stand-in for New York or some other vague metropolis. When The Answer Man (2009) director John Hindman was asked why he filmed in the city, he said, “Because of their wonderful tax incentives.” When the tax credits were reduced under Governor Tom Corbett (b.1949) to $60 million and then $42 million in fiscal year 2009-10, movies that had planned to use Philadelphia moved elsewhere. Brad Pitt’s World War Z (2013) made Glasgow, Scotland, into Philadelphia because the tax credit deal fell through.

Although the tax credits recovered from their post-recession decline and remained stable at $60 million in 2015, their fruits were spread across the state, and Philadelphia was not guaranteed a pride position. Only one major studio picture filmed in Philadelphia in 2015: Ryan Coogler’s (b. 1986) Creed, the seventh sequel to Rocky, focused on the city, a welcome return to the neighborhood-based story telling of the first Rocky. Another major studio production, Clerks III, was shot in Philadelphia, but in this instance Philadelphia stood in, again, for New York. Thus while Philadelphia managed to retain some role in film into the twenty-first century, its position remained a pale shadow of its promising beginnings.

Jake Blumgart is a reporter, editor, and researcher based in Philadelphia. He is a contributing writer at Next City and PhillyVoice. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Pennsylvania's film tax credit panned, praised (WHYY, August 8, 2011)

- 'Silver Linings Playbook' draws diners to special booth at Llanerch (WHYY, January 10, 2013)

- 'Silver Linings Playbook' team won't be back in Philly for new Abscam movie (WHYY, March 4, 2013)

- 'World War Z' set but not filmed in Philly. Why? (WHYY, June 21, 2013)

- Two decades agoTom Hanks and 'Philadelphia' prompted changing attitudes toward HIV-AIDS (WHYY, December 20, 2013)

- Kevin Smith to shoot 'Clerks III' in Philly (WHYY, March 13, 2015)

- Rocky, super salesman (WHYY, June 4, 2014)

- 'Rocky' road leads back to Philly with 'Creed' movie (WHYY, November 6, 2015)

Links

- Lubin Manufacturing Company Records (Free Library of Philadelphia)

- Siegmund Lubin Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.org)

- Pennsylvania Film Office (FilminPA.com)

- The Real Tracy Lord (Reel Classics)

- Philadelphia at the Movies (PhillyHistory Blog)

- Esther Pennington on the Lubinville motion picture studio, 1915 (ExplorePAHistory)

- Philadelphia-haunted David Lynch returns for an expansive salute (Philadelphia Inquirer, September 8, 2014)