Greater Philadelphia Movement

Essay

The reform wave that swept through City Hall in the mid-twentieth century owed much of its power to the Greater Philadelphia Movement (GPM), a volunteer group of corporate leaders who believed the city’s scandalous political corruption threatened its economic future. Formed in 1948, they called themselves “practical men” who wanted Philadelphia to work more effectively for both residents and investors. GPM members represented economic sectors like finance, insurance, law firms, and banks that were challenging the longstanding dominance of manufacturing businesses in the city’s economy and politics.

The example of Pittsburgh’s Allegheny Conference, formed in 1944, had shown that active and well-organized business leaders could effectively join with political leaders to rebuild faltering cities. Among GPM’s most influential early members were C. Jared Ingersoll (1894-1988), railroad executive and banker; Robert T. McCracken (1883-1960), a leading Republican lawyer; and William Fulton Kurtz (1887-1969), president of First Pennsylvania Bank & Trust Co. Along with about two dozen colleagues, they saw political reform, physical renewal, and economic growth as interrelated issues. They proceeded problem-by-problem, each time investigating its nature and scope, proposing solutions, and handing the project off to another organization to implement solutions. If no organization existed to take on the task, GPM launched a new one–for example, the Food Distribution Center Corporation. GPM’s executive director and small staff were paid by contributions from the members and their firms.

GPM began by revising the city charter, the legal document defining the organization, powers, and functions of Philadelphia city government. The political scandals of the 1940s had convinced its leaders that the city required a new charter to eliminate corrupt practices and ensure more efficient delivery of city services. The new charter that GPM promoted created a strong mayor government, removing the City Council from administrative roles it had been playing and instead making all city departments report to a managing director. It introduced a strong merit system for staffing city departments, allowing them to hire only candidates that had been vetted by the Civil Service Commission.

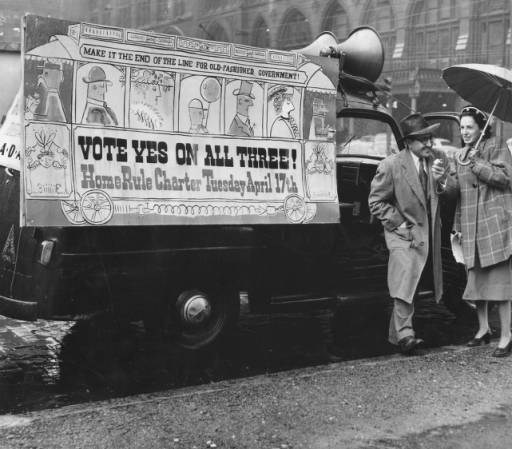

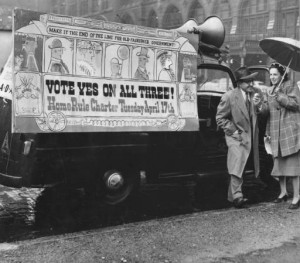

Once drafted, the reform charter had to be ratified by Philadelphia voters. They required serious persuasion, especially because the established political parties opposed changes that would disrupt machine politics. To orchestrate the successful campaign for voter support, GPM formed in 1949 a new civic organization, the Citizens Charter Committee, which eventually consisted of representatives from five hundred social, fraternal, religious, and community organizations. The Chamber of Commerce raised $80,000 to fund the campaign waged by this network of civic organizations that ultimately won the voters’ approval for the reformed charter in April 1951. That same year Joseph Clark (1902-90) became the first reform mayor with support from GPM.

Physical redevelopment was another important priority for GPM. An early goal was eliminating the hazardous, decrepit downtown food market where fruits and vegetables were trucked into town and sold to local grocers and restaurants. Created in the days of horse carts, the Dock Street Market by the 1950s had become the cramped destination of 15,000 trucks per day. GPM spearheaded the project, launching the nonprofit Food Distribution Center Corporation in 1954 that removed this health and fire hazard from Society Hill and relocated it in a new Food Distribution Center built on 388 acres between Packer and Pattison Avenues in South Philadelphia.

During the 1960s GPM shifted its efforts to Philadelphia’s failing public schools, which operated primarily as a haven for patronage. Common Pleas judges appointed the members of the school board in a politically-driven process. Both teaching and nonteaching jobs were filled through patronage. Having succeeded in revising the city charter, GPM members successfully pressed Pennsylvania’s General Assembly to permit the Philadelphia City Council to create an Educational Home Rule Charter Commission to reform public school governance. Once established, the commission recommended assigning the mayor responsibility for selecting school board members from a list proposed by a nonpartisan citizens panel. GPM took a strong hand in the campaign to win voter approval for the change, using a strategy similar to the charter campaign–founding a Citizens’ Education Campaign Committee co-chaired by Richardson Dilworth (1898-1974) and Thacher Longstreth (1920-2003) that included many of the same citizen activists who had campaigned for the charter. Arguing that a nonpartisan panel would assure higher-quality nominees for the school board than patronage politics had produced, they secured public approval in a referendum in May 1965. A month later the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin lauded GPM as “the cream of civic group giants,” the “powerhouse of Philadelphia’s citizen elites,” and “the combat and control center of the city’s movers and shakers.”

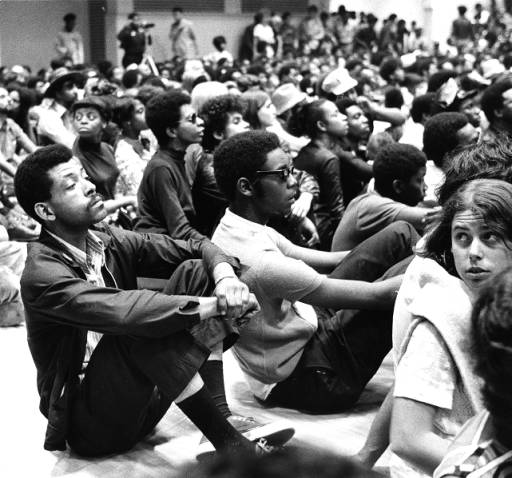

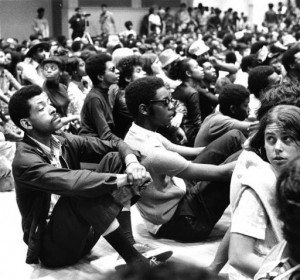

GPM occasionally took stands not usually associated with business coalitions. A very public example occurred on Labor Day weekend 1970. Temple University had agreed to host a national convention of the Black Panther Party on its North Philadelphia campus. Responding to significant public opposition as well as incendiary comments from Police Commissioner Frank Rizzo (1921-1991), some Pennsylvania state legislators demanded that the university cancel the event in order to avoid civil unrest, whereas Governor Raymond Shafer (1917-2006) argued that despite their unpopularity, the Panthers were entitled to express their views publicly at an open convention. GPM surprised many by supporting the Panthers’ convention on the opinion page of the Bulletin: “We call upon all Philadelphians to understand and accept the vast difference between supporting the rights of others (to peaceful assembly) and agreeing with their views.” In the end, the convention drew thousands of participants to a peaceful event.

Despite its successful record, by the early 1970s business commentators were raising doubts about GPM’s future. Underneath the headline “Once-Powerful GPM Turns Flabby,” Lou Antosh and Peter Binzen reported that for the first time since GPM’s founding, business leaders were turning down invitations to join. To sustain itself, GPM merged in 1973 with another civic improvement organization, the Philadelphia Partnership, to become the Greater Philadelphia Partnership. Subsequently in the 1980s that group transformed itself again, expanding its concern beyond the city to the wider metropolitan region and calling itself the Greater Philadelphia First Corporation, which subsequently merged in 2003 with the regional Chamber of Commerce.

That trend of gradual shrinkage and consolidation reflected the diminishing role of corporate leadership In Philadelphia as in other U.S. cities. When corporate executives started moving more frequently from city to city, they took less interest in civic improvement. Mirroring that trend, the city’s mayors, starting with James Tate (1910-83) in the mid-1960s, began to pay less attention to policy advice from business leaders. Perhaps the most important explanation for diminishing corporate influence was that so many large corporations moved to the suburbs, giving their executives less motivation to invest time and money in systematically tackling the city’s deepest problems. In its early days, Mayor Joseph Clark had urged GPM to pursue city-suburban cooperation, but its members had shied away from what they saw as a goal that might take generations to achieve. Instead, they chose to focus their efforts on near-term objectives.

Carolyn T. Adams is Professor Emeritus of Geography and Urban Studies at Temple University and associate editor of the Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History