Hinterlands

Essay

Since its founding, Philadelphia has acted as a commercial hub for the surrounding region, its hinterlands. Although New Jersey and Delaware had European settlers before Philadelphia’s establishment in 1682, Pennsylvania and its founding city quickly became the focus of economic activity in the region extending both east and west of the Delaware River. With an advantageous location, Philadelphia acted as the region’s principal port, allowing goods from Great Britain, the West Indies, and elsewhere to flow in and serving as a gathering point for produce to be exported. From the late seventeenth through the eighteenth century, Philadelphia’s hinterlands grew in size and diversification of products, but as the region developed, other commercial hubs developed to support and rival Philadelphia.

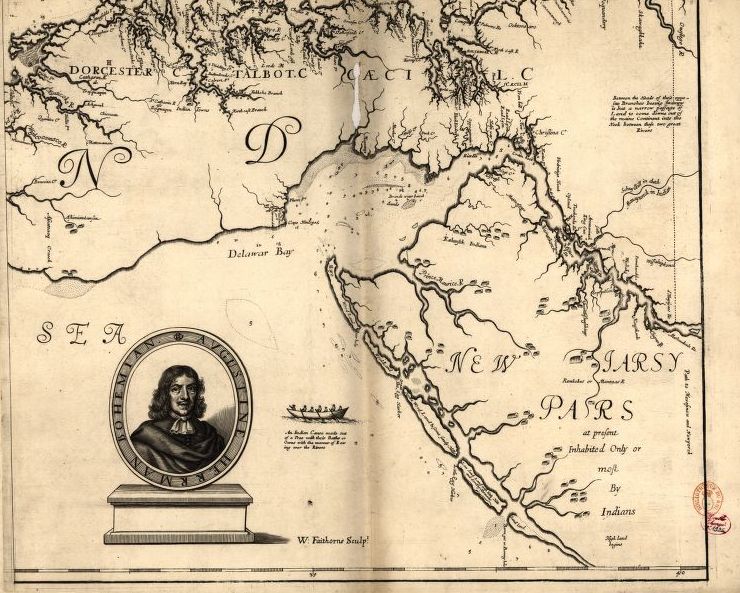

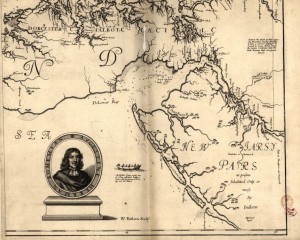

The Delaware River Valley was originally populated by the Lenape, or Delaware, people, who shaped the region’s initial economic activity. Throughout the seventeenth century, the Lenapes retained a strong presence in the river valley, and the various native and European groups generally worked with each other through trade and negotiated rights and privileges. Native American trails became the earliest paths for the colonists, aiding travel, communication, and commerce into the densely forested hinterland. During this early period, Europeans tapped into the preexisting fur trade before developing their own settlements inland. The territory that later became the state of Delaware was first colonized in 1638 by the Swedish, who adopted a plantation pattern in an attempt to emulate Virginia’s success with tobacco. However, these settlements were underpopulated, of limited profitability, and experienced conflicts with the local Lenape groups. From 1676 through 1702, New Jersey was divided by a line running from the northwest to the southeast, creating the distinct provinces of East and West New Jersey. West New Jersey was administered by a group of wealthy Quakers, including William Penn (1644–1718), but it was sparsely populated and had no major cities of its own.

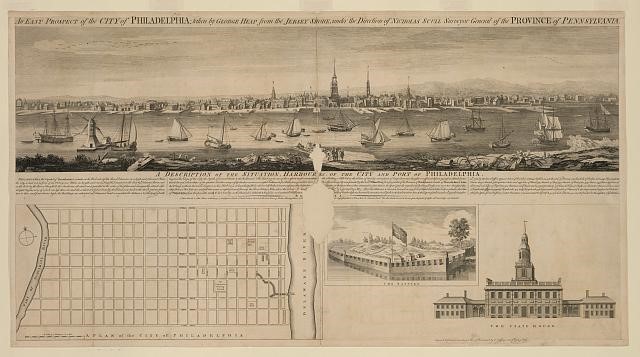

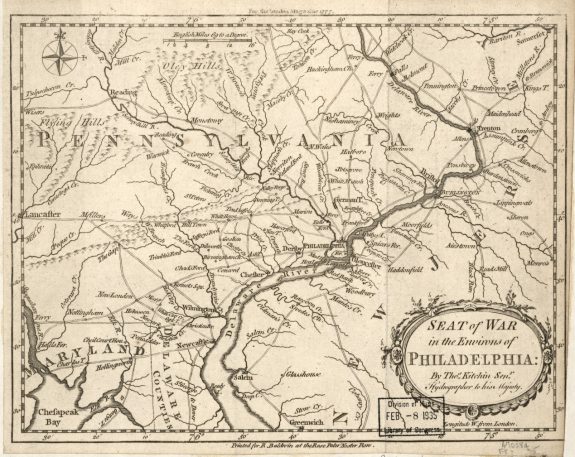

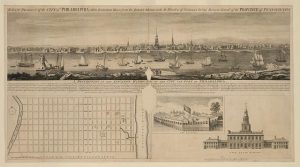

After the founding of Philadelphia in 1682, the region’s producers saw the new city as a natural commercial center for the Delaware River. William Penn (1644-1718), founder and first proprietor of Pennsylvania, selected a site near the confluence of the Schuylkill and Delaware Rivers to better facilitate shipping. Pennsylvania grew quickly during the five decades before the American Revolution, adding eight inland counties to the original counties huddled by the river (Bucks, Philadelphia, Chester, and the lower counties that later became Delaware). Immigrants—free, indentured, or enslaved—strengthened the hinterlands’ connection to the burgeoning urban center as they spread through the countryside. In addition to Quakers and other English colonists, Pennsylvania attracted Scots-Irish, Germans (including the “Pennsylvania Dutch”), and dissenting religious groups.

Population Boomed

At first, in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, Philadelphia primarily exported raw farm products and timber from these homesteads of the fertile Delaware River valley lands, and the numerous creeks and rivers served as transportation routes for the goods. In the eighteenth century, the European colonists developed their own settlements in the hinterland areas. Timber resources allowed for a vigorous shipbuilding enterprise. The plantations of Delaware Bay moved away from tobacco to more diversified farm products such as meat, grain, and timber. The population boomed from migration from the Chesapeake Bay region and immigration abroad, though the towns and cities that grew remained satellites of Philadelphia.

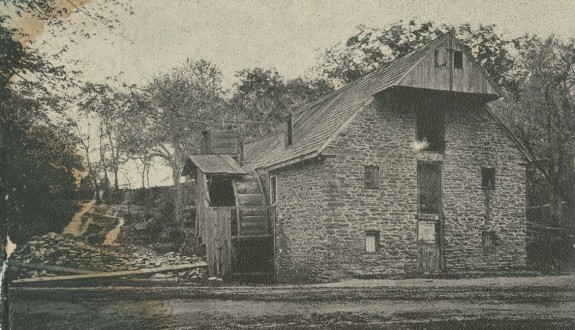

By 1750, increasing grain production made Philadelphia’s hinterland the breadbasket of the British Empire. The new emphasis led to an increase in flour mills for processing the grain. Mills of various kinds operated throughout the hinterland but had the highest concentration and outputs in Pennsylvania and northern Delaware, where fertile lands combined with strong streams for waterpower to facilitate the milling of grain. Likewise, iron production and its attendant forges and foundries grew during the same period, primarily in Berks and Lancaster Counties in Pennsylvania and in western New Jersey.

Supplies of timber, flour, iron, and similar stores made Philadelphia an important provider of war materials during the colonial wars. However, the Seven Years’ War (1754-63), which erupted from conflicts in far western Pennsylvania, interfered with trade. In Pennsylvania specifically, it created conflicts over the extent of protection the colonial assembly would provide for the hinterlands as the area suffered from destructive raids. During the War for Independence, Philadelphia and its Pennsylvania hinterlands experienced disruption but not for extended periods of time, allowing economic activity to largely continue and cement its role as a producer. By the end of the eighteenth century, it led the new nation in production of textiles and leather goods, as well as metalworking and carpentry.

Road Improvements

In the late eighteenth century, the creation and improvement of roads from Philadelphia deep into the hinterlands eased travel, improving freight transportation but also pushing the frontiers beyond its reach. Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) advocated for improving road networks, emphasizing the communication benefits as postmaster general. Improving communication and mail helped information from centrally located Philadelphia reach its hinterland and other colonies (later states) faster than ever, further increasing Philadelphia’s economic and political influence. In 1794, Pennsylvania completed a paved turnpike connecting Philadelphia with Lancaster, which lowered transportation costs by as much as two-thirds and was the first of its kind in the nation. This simultaneously drew Lancaster more into Philadelphia’s orbit, and made it a commercial center in its own right, as a gathering point for central Pennsylvania’s goods.

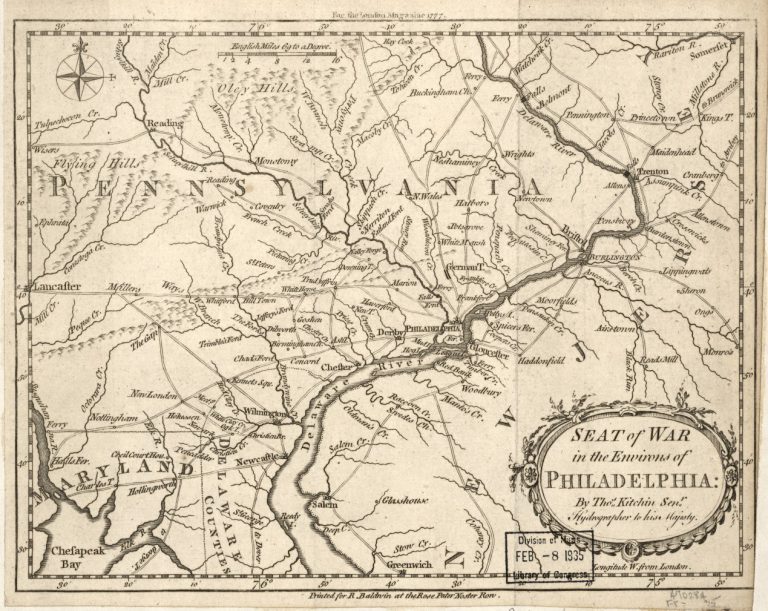

By the turn of the nineteenth century, Philadelphia’s hinterland reached as far west as Lancaster and Reading on the Schuylkill River, and the city’s influence extended to the edge of the Appalachian Mountains and the Susquehanna River watershed. The city commanded the Delaware River Valley as far north as Trenton at the falls of the Delaware. Ships going in and out of Delaware Bay called on Delaware’s smaller ports, such as Wilmington and New Castle, creating a connection for Philadelphia at those locations as well. During the same period, however, New York City to the north and Baltimore to the south increasingly grew and rivaled Philadelphia as leading international ports for the mid-Atlantic states, especially from north of Trenton and the Susquehanna Valley, respectively.

From the time of its founding, Philadelphia’s location and natural resources made it a commercial hub for the surrounding region. As the eighteenth century progressed, manufacturing capabilities increased and Philadelphia’s exports became more diversified while the city increasingly grew as a commercial and political center through the periods of the American Revolution and early Republic.

Jordan AP Fansler grew up in Pennsylvania, is a graduate of Saint Joseph’s University in Philadelphia, and has worked at multiple museums in Greater Philadelphia. His doctoral thesis and scholarly work focus on the relationship of citizens to their state, national, and imperial governments in the early-modern Atlantic World. (Author information current at time of publication)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- The Water Wheel at Hopewell Furnace (National Park Service)

- Colonial Pennsylvania Plantation

- Philadelphia as a Central City in the Atlantic World (Philadelphia: The Great Experiment)

- Agriculture and Rural Life (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- On the Water: Living in the Atlantic World (National Museum of American History)