Junto

Essay

“Do you love truth for truth’s sake?” If the answer is yes, you are one-fourth of the way through the initiation ceremony of the Junto, which Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) founded in 1727 in Philadelphia. The 21-year-old Franklin, according to his autobiography, established the Junto as a club for “mutual improvement,” inviting acquaintances to meet weekly to discuss intellectual and moral issues. From these discussions emerged inspiration for many Philadelphia institutions including the American Philosophical Society, the Library Company of Philadelphia, a fire company, and the University of Pennsylvania.

The name and concept for the Junto came from Franklin’s experiences working as a typesetter for several years in London. Not only was “Junto” used to describe a particularly select and powerful group of liberal Whig parliamentarians of the time, but also London was crammed with gentleman’s clubs aimed at encouraging the exchange of knowledge and strengthening of ties between businessmen. It is equally fitting that Franklin lifted the initiation ceremony from the writings of John Locke (1632-1704), a prominent Whig. Locke’s writings had linked intellectual scenes in London and Philadelphia as early as 1699, when William Penn (1644-1718) arranged regular shipment of Locke’s works to the young colony.

In addition to a love of truth, Junto members pledged not to disrespect one another, not to disrespect persons based on their profession or religion, and not to condone violence against anyone “in his body, name, or goods, for mere speculative opinions, or his external way of worship.” These pledges mimic those that Locke devised in his own “Rules of a Society, which met once a week for their improvement in useful Knowledge.”

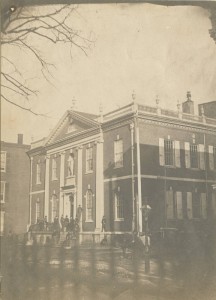

With tolerance at the base of operation, Franklin presided over the club’s discussions on morality, politics, natural philosophy, and local gossip. Membership was capped at twelve, and members worked in diverse trades (scrivener, glazier, cobbler, surveyor, cabinetmaker, clerk) with diverse tastes (poetry, astrology, natural history, mathematics, scientific invention). They met every Friday night, in early years at the Indian Head Tavern but for privacy later changing the location to Robert Grace’s house on Market near Second Street. Grace was the only early member of the Junto considered a “gentleman,” with no craft or profession.

Incubation Chamber for Improvements

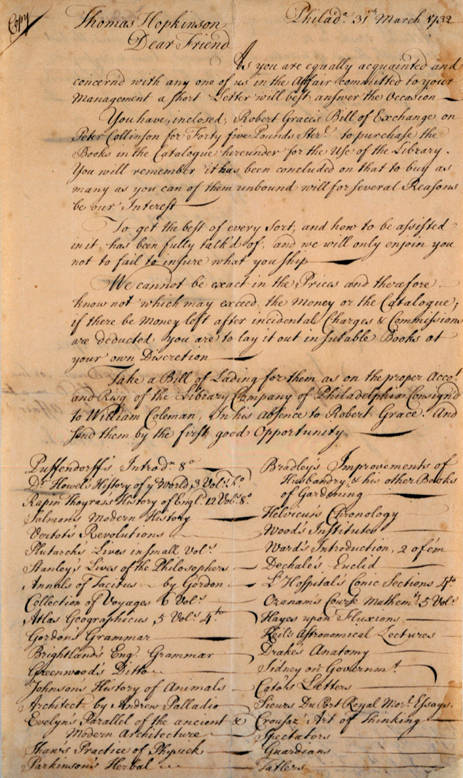

In his biography of Franklin, University of Delaware scholar Leo LeMay (1935-2008) described the Junto as the “incubation chamber” for projects that greatly improved life in greater Philadelphia. Members ran a lending library prefiguring the Library Company, considered the potential of paper money, which Franklin eventually printed, and discussed his ideas for a fire company, insurance company, local militia, and town watch. The Junto’s interest in scientific experiment also featured in their meetings, inspiring the founding of the American Philosophical Society in 1743. The Junto’s William Coleman, Jr. (1704-69), Thomas Hopkinson (1709-51), and Philip Syng (1703-89) were all founding members of the APS. The Junto also endorsed education and civic awareness, and thus supported the academy Franklin founded in 1751 that enshrined these values in the curriculum of what later became the University of Pennsylvania.

The Junto members were not just men of words, but deeds, when it came to furthering Franklin’s ideas. For instance, Coleman was the first treasurer of the Library Company (1731), treasurer of the American Philosophical Society (1743), a trustee of the Academy of Philadelphia, and one of the directors of Franklin’s insurance company. Coleman was not atypical. The Junto’s Joseph Breintnall (d. 1746) served as first secretary of the Library Company, and Philip Syng was a trustee of the Academy of Philadelphia.

Franklin’s description of the group’s convivial meetings offers a lovely glimpse into the playful side of 18th century intellectual life. Members recited silly poems, songs, played the flute drunkenly, and gave each other nicknames—“Bargos” for Ben. As Franklin wrote to Hugh Roberts (1706-86) in 1761, “I find I love Company, Chat, a Laugh, a Glass, and even a Song, as well as ever…I therefore hope [the Junto] will not be discontinu’d as long as we are able to crawl together.” But meetings were held less frequently when Franklin, the driving force behind the Junto’s activities, departed on a diplomatic mission to England in 1764. By 1765 Roberts wrote back to Franklin that in addition to his absence, the Junto’s dissolution had dovetailed with political divisions in Pennsylvania.

Although the group was comparatively small, its impact was wide-ranging on the everyday lives of those living within its orbit. The “crawling together” of its members, their intellectual and financial collaboration, ensured the success of each project beyond the life of the club itself.

Brooke Sylvia Palmieri is a Philadelphia native living in London, working toward a Ph.D. at the Centre for Editing Lives and Letters at the University College London. Her dissertation details the reading, writing, and publication habits of Quakers at the end of the seventeenth century and how they circulated their ideas from London across the sea to the British colonies in the West Indies and North America. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University