Levittowns (Pennsylvania and New Jersey)

Essay

The iconic Levittown communities–the first in Long Island, New York, and the subsequent two in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, and Burlington County, New Jersey–endure as symbols of the unique character of post-World War II U.S. suburban development. A confluence of forces encouraged the particular nature of these large-scale, mass-produced, low-cost suburban tract housing developments, including a shortage of housing for returning veterans and their young families, the rise of new building techniques, and federal government mortgage financing incentives. Levitt and Sons builders of New York, led by Abraham Levitt and his two sons William Jaird (1907-94) and Alfred (1912-66), seized the opportunity to afford home-ownership to masses of middle- and working-class Americans.

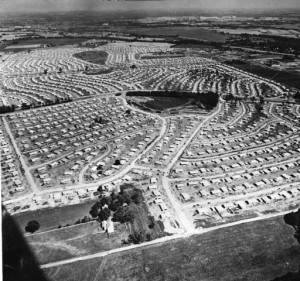

Early suburban development had been incremental, custom-oriented, and expensive, which limited life on the metropolitan periphery to a wealthy few. Levitt and Sons, however, were at the forefront of the trend toward mass-producing smaller housing units in large subdivided communities. In the early 1940s, the Levitts gained experience in erecting modest homes quickly through war-related federal contracts in and around Norfolk, Virginia, to meet the acute demand for housing the area’s substantial naval population. After the war’s end, the Levitt organization quickly adapted for the broader market its newfound expertise constructing affordable housing in a way that resembled the assembly-line production of automobiles. Standardized houses were built on concrete slabs using precut components. Subcontractors would move from house to house, performing their single task with such great efficiency that, at the height of production, a Levittown house was completed every 16 minutes. The largest housing development ever produced by a single company, Long Island’s Levittown included more than 17,400 single-family detached homes each of roughly 750 square feet equipped with a state-of-the-art built-in kitchen. By 1950 Levitt and Sons had risen to become the largest homebuilder in the country.

Levittown, Pennsylvania

Like Levitt’s Long Island development, Pennsylvania’s Levittown benefited from the federal Veterans Administration program to provide loan guarantees that allowed veterans to buy homes with little or no down payment. But Pennsylvania’s Levittown was firmly connected to the area’s industrial base. The developer chose this site because U.S. Steel Corporation’s Fairless Works Plant had just broken ground nearby alongside the Delaware River, and thousands of plant employees would need convenient housing. In 1951 Levitt and Sons bought 5,750 contiguous acres of broccoli and spinach farmland near that plant to build what the company claimed was “the most perfectly planned community in America.” Many of Levittown’s initial buyers were employed at the Fairless Works plant.

The Levitts built slightly more than 17,300 homes of only six different models between 1952 and 1958 in this second Levittown. The community was partitioned into four master block areas, which in turn were divided into smaller neighborhood sections of between 300-500 houses. Each section was assigned a general name, and streets within that section were given names beginning with the first letter of the section name. Thus, Hollyhock Lane and Hickory Lane are found in the Holly Hill neighborhood. Sections were kept intimate to encourage community interaction while master block areas were separated by larger through streets such as Levittown Parkway. Community amenities were part of the package with space set aside for a shopping center and places of worship, an elementary school in each master block, and the inclusion of baseball fields, neighborhood parks, and five community swimming pools managed by the Levittown Public Recreation Association.

Levittown, Pennsylvania, is a Census Designated Place in Bucks County that was carved out of farmland that had been incorporated into existing municipalities well before Levitt bought the land. As such, it meanders through Bristol, Falls, and Middletown Townships, and Tullytown Borough. This fragmentation among four municipalities and three school districts undermined the cohesiveness of William Levitt’s community vision. Levitt would have preferred to secure incorporated status for Levittown as a separate township; however residents refused to support the proposal fearing it would increase their tax bills.

Levittowns were notorious as all-white communities. William Levitt famously proclaimed that “we can solve the housing problem or we can solve the racial problem, but we cannot combine the two.” The national spotlight blazed on Levittown, Pennsylvania, as a battleground for suburban housing integration when, in August 1957, an African American couple, Daisy and William Myers, bought and moved into 43 Deepgreen Lane in the Dogwood Hollow section with their three young children. A year of racist harassment and sometimes violent provocation against the Myerses led religious groups like the Quakers to join with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People to try to force local police to protect the Myers family. Ultimately the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania issued an injunction to stop what it called “an unlawful, malicious and evil conspiracy” by Levittown neighbors and convicted the ringleaders of violating the Myerses’ rights.

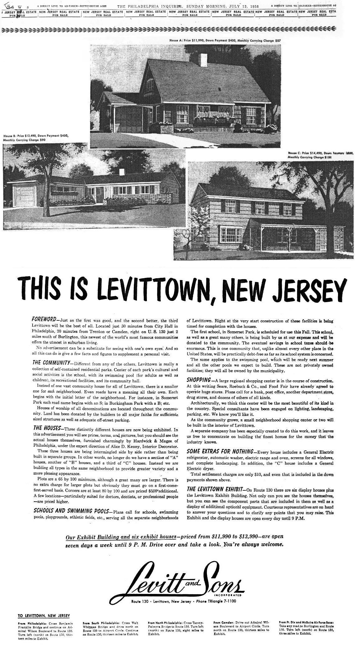

Levittown, New Jersey

With the construction of his third Levittown, William Levitt could realize to its fullest extent his vision of a comprehensively planned community. In the mid-1950s the company used straw purchasers to buy farmland in Burlington County, an area within easy commuting distance to Philadelphia, Camden, and Trenton. Levitt used seemingly unrelated buyers, as he had previously done in Pennsylvania, to discourage sellers from delaying the sales in the hopes of getting higher prices per acre. In New Jersey, Levitt was determined that his new development would not repeat his earlier mistake in Pennsylvania of crossing municipal boundary lines, which had forced him to deal with conflicting zoning and subdivision regulations. In the end, Levitt acquired about 90 percent of all the land located within the borders of the single township of Willingboro. There he built 11,000 homes, selling the first in June 1958. The township was officially renamed Levittown in 1959 by resident referendum. But by 1963 the confusion with Levittown, Pennsylvania, in the same metropolitan area prompted residents to change the town’s name back to Willingboro.

Levitt notably offered mixed housing types on streets in Levittown, New Jersey, such that a more expensive “House C (Colonial)” could be found next door to the more modest “House A (Cape Cod).” The adjustment was meant to allay criticism from urban theorists, most notably Lewis Mumford, that the new suburban developments suffered from a depressing uniformity. The mix of housing types at different prices was intended to draw more middle- and upper-middle-class buyers than had been attracted to the earlier Levittowns. And in fact Herbert Gans’ acclaimed 1967 sociological study, The Levittowners, confirmed the community’s socioeconomic diversity. Gans documented subtle but important variations in class, religion, lifestyle, and political orientation among early Levittown, New Jersey residents.

As Levitt was building Willingboro, his company was already under legal assault for the whites-only policy in its Pennsylvania development. Since the New Jersey location was close to several military bases, it drew interest from military personnel including an African American Army officer, Willie R. James, who integrated the new community by winning a 1960 lawsuit against racial exclusion. Rather than public harassment and violence, racial conflicts were settled by litigation, which gradually made Willingboro appear safe to more and more minority homebuyers but prompted whites to leave. Although the town leaders tried to stem white flight by banning the public display of “for sale” signs, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the ban. By the 2010 U.S. Census about seventy-three percent of the population identified as “One Race: Black or African American.”

In contrast, Levittown, Pennsylvania, remained predominantly white with about ninety percent identifying as “One Race: White” in the 2010 U.S. Census. One contributing influence may have been the prominent role of the Fairless Hills plant in the life of Levittown. That U.S. Steel mill was several times charged with discrimination against African American workers. Almost certainly, the well-known violence and hostility faced by early residents of color in Levittown discouraged other African American families from moving there.

Enduring Legacy of the Levittowns

The massive scale of these low-cost single-family detached housing developments, coupled with William Levitt’s grandiose persona, catapulted the Levittown brand as the national symbol of the unique nature of postwar mass-migration to suburbia. Criticism abounded of the new American lifestyle in the “cultural wasteland” of cookie-cutter, “little boxes” that typified new tract housing. However, projects such as Gans’ study, architects Denise Scott Brown and Robert Venturi’s “Learning from Levittown” that analyzed the changes owners made to their homes and yards, and sociologist David Popenoe’s account of Levittown, Pennsylvania’s maturation after twenty years in existence, revealed a more complex life and landscape in these places.

Levittown and Willingboro remain economically stable communities with median household income, according to the 2013 American Community Survey (ACS), at $69,066 and $67,697 respectively, both above the metropolitan area’s median of $60,482. But the two communities’ fortunes differ in many respects. Unemployment in Levittown was 5.8 percent, according to the 2013 ACS, but higher in Willingboro at 10 percent. Median house value was also strikingly different with the 2013 ACS recording Levittown’s as $230,000 and Willingboro’s as $169,500 even though Levitt built more upscale housing at the New Jersey site. And while the persistent white-majority in Levittown mirrors the overwhelming white-majority composition of the four Levittown municipalities as well as Bucks County in general, Willingboro’s African American majority stands in stark contrast to the white-majority racial makeup present in all other Burlington County municipalities.

One possible explanation for the differing trajectories of these two Levittown communities, apart from their disparate histories, may lie in the difference in choices available to contemporary homebuyers seeking an ideal suburban township setting. Since the sections of Levittown, Pennsylvania, remain essentially only neighborhoods within larger municipalities, they offer the most affordable choices within those jurisdictions for people of limited resources, while the diversity of neighborhoods and housing types means that wealthier buyers interested in purchasing within those municipalities have options for newer housing styles in different kinds of settings. In Willingboro, on the other hand, since the now outdated Levitt-style development constitutes the vast majority of the township’s housing stock, buyers interested in other kinds of neighborhood layouts or housing styles must look in other municipalities. This explanation suggests a flaw in Levitt’s vision of creating one type of neighborhood within the confines of a single jurisdiction. Developing almost the entire township at a single moment in time limited Willingboro’s ability to update incrementally in response to evolving residential and commercial sensibilities.

Levittowns began as symbols of America’s post-war promise and progress. These communities have been much studied and documented as the archetypal late-twentieth -century landscape of the unfolding American story. The trend toward suburban privatization is illustrated in the literature by the closing of the majority of Levittown, Pennsylvania’s once thriving community pools and the introduction there of property-line fences. Its integration struggles exposed the segregated nature of U.S. suburbanization. Scholars agree that Levittown was a singular American achievement that forever changed the dynamic of suburbia. With the creation of Levittown, masses of working-class Americans, albeit white-only, could own a piece of picture-windowed suburban America with its lure of wholesome living and good schools. More than 60 years after the Levitts first sold low-cost homes, these two Levittowns still proved an affordable option for people of ordinary means seeking home ownership in a suburban setting.

Suzanne Lashner Dayanim holds a Ph.D. in Geography and Urban Studies from Temple University. Her dissertation measures the value of community facilities to inner ring suburban resilience, and its study area includes the four municipalities of Pennsylvania’s Levittown. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Levittown, Pa. : Building the Suburban Dream (The State Museum of Pennsylvania)

- Levittowners

- The Township of Willingboro

- Levittown Beyond

- Walt Disney Elementary School, Levittown, Pa., registration for National Register of Historic Places (National Park Service, July 15, 2007)

- Levittown Classic Movies Presents: Our Home Town

- Levittown Classic Movies Presents: Crisis in Levittown, PA