Liberia; Or, Mr. Peyton’s Experiments

Essay

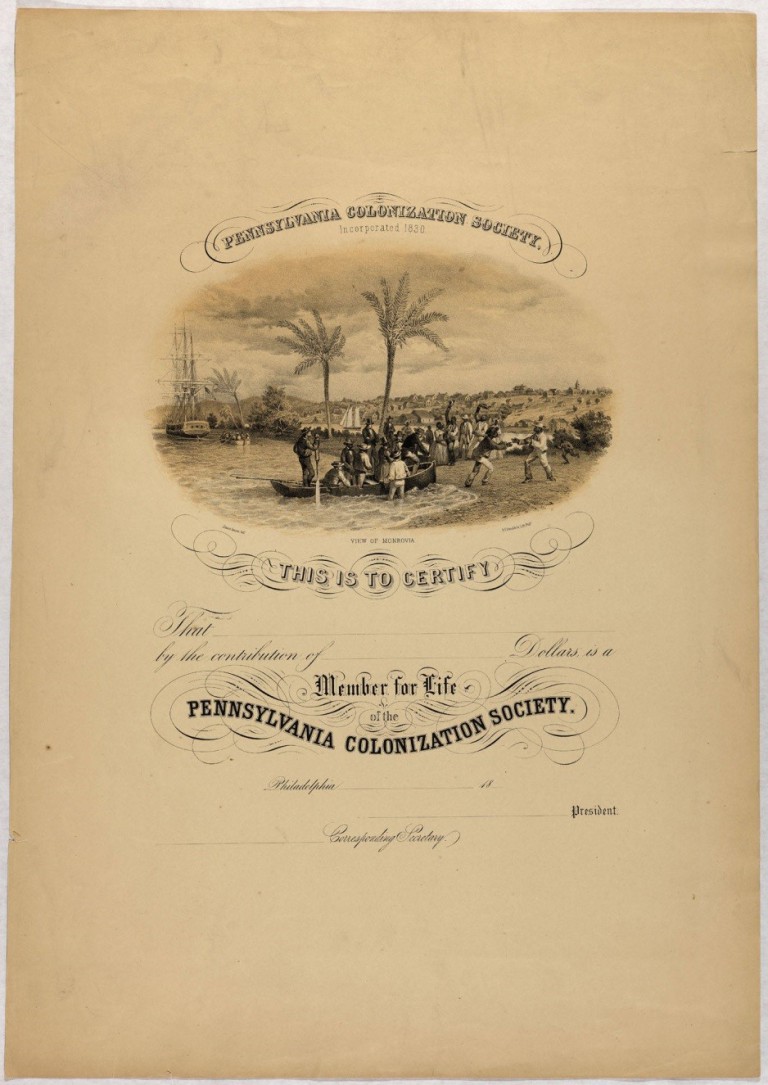

Liberia; Or, Mr. Peyton’s Experiments (1853) is a hybrid work containing fiction, history, and biography along with transcriptions of documents on Liberia. The work argued that free Black people could not prosper in North America but had opportunities for advancement and self-determination in Liberia, a Black Christian republic. The Americo-Liberian settlers would not only rise themselves but would also bring the supposed benefits of commerce, Christianity, and civilization to indigenous Africans. Thus the work promoted the expatriation movement known as African colonization.

Sarah Josepha Hale (1788–1879), listed as editor of the work, was more author than editor. A Philadelphia resident and major spokeswoman for both American patriotism and moderate progress for women in the nineteenth century, Hale promoted efforts like the establishment of the national Thanksgiving holiday, the construction of the Bunker Hill monument, and the preservation of George Washington’s plantation, Mount Vernon. She extolled the moral and domestic virtues of middle class white women, yet she envisioned their participation in the workplace and she assisted in the founding of Vassar College.

The book begins with a fictional account of the white Virginian Peyton family and the Black people they held in slavery. After the enslaved people prove loyal during a slave insurrection, Charles Peyton experiments with manumitting them, initially into agricultural labor with the opportunity for freeholding, then into urban employment and self-determination in Philadelphia, and at last, after 1820, into citizenship in a so-called Black republic, Liberia. Following is a semifictional account weaving the lives of freed Peyton slaves Keziah, Polydore, Nathan, Junius, Ben, and Clara into the history of Liberia as Hale garnered it from contemporary publications. Hale generally stayed true to her sources on Liberia, although she tailored the biographies of some early settlers to suit her work. Finally is a collection of transcribed letters, addresses, and legal documents on Liberia.

Philadelphia’s Dual Roles

Philadelphia played two crucial roles in Liberia. It was the city to which Peyton sent his freed slaves (after the failure of the rural agricultural experiment) to test whether they would advance as urban dwellers, and it was the origin of several of the Americo-Liberians whose letters Hale included. Hale apparently focused on Philadelphia partly because she lived and worked there (as editor from 1837 to 1877 of Godey’s Lady’s Book) and partly because the city was indeed home to a significant population of free African Americans.

As a testing ground of freedom for Ben, Clara, and Americus (another freed Peyton slave), Philadelphia fails miserably. Ben and Clara initially fare well, employed by well-to-do white Philadelphians as a carriage driver and a seamstress. However, they are lured into improvident consumption such as extravagant clothing and music lessons for their daughter. Americus is beaten by a marauding white mob as he is, at his employer’s request, accompanying a young white woman to her home after a social event. Having failed to save for hard times, Ben and Clara become impoverished when illness causes the loss of Ben’s job. He becomes an alcoholic and his family become dependent on the charity of whites for food and clothes. Only communications from the freedpeople who had emigrated to Liberia give the new Black Philadelphians reason to improve themselves, and only Liberia itself provides the context for self-improvement.

Philadelphia is, in Liberia, a city in which free Black people leap to dizzying heights of conspicuous consumption while ignoring the facts that they are skating on thin ice economically and that white America will never fully accept them. In this, Hale was following broadside caricatures of free Black Philadelphians that Edward Williams Clay (1799–1857) had published around 1830. Hale’s Americus, after visiting Paris, returns to Philadelphia more desirous of fine possessions and more bitter about American racism.

Hopes for Prosperity in Africa

It was essential to Hale’s colonizationist views to present “facts” about Black Philadelphians in Liberia. Some of the emigrants came from nearby locations like Camden, New Jersey, while others left Philadelphia first for Baltimore, then for Monrovia. Hale understood that the greater Philadelphia region was deeply involved in colonization. The view of Liberia expressed in the letters Hale collected is that Black Philadelphians, if committed to solid advancement and not frippery, can prosper in Africa. For instance, Charles Deputie (1809–68), “born free . . . a native of Pennsylvania,” wrote from Monrovia on January 10, 1853, that only “industrious men and good mechanics” were wanted in Liberia. He proposed to plant 500 acres of coffee trees and “have it settled by none but respectable people from Pennsylvania.” He continued, “some from Philadelphia . . . would have a good effect.” Writing from Buchanan, January 17, 1853, H. M. West, who closed his letter with, “I was originally from Philadelphia,” assured the reader that in Liberia, “‘The flesh-pots of Egypt’ present no attraction to me.” Despite her low opinion of free Black Philadelphians, Hale believed that Philadelphia could funnel “industrious men” and their families to a new and better home in Africa.

Colonizationist thought was racist and pessimistic. It assumed that free Black people could never adapt to social life in North America. It took for granted that a critical mass of whites would bar equality for African Americans. Still, Hale criticized slave traders and slaveholders, she was sensitive to the sufferings of the poor (even if she sometimes blamed them for hard circumstances), and she condemned whites for behavior ranging from violence against Blacks to refusal to hire free African Americans. Liberia clearly encompasses both racist sentiments and objections to anti-Black racism.

John Saillant is Professor of English and History at Western Michigan University. He is the author of the monograph Black Puritan, Black Republican: The Life and Thought of Lemuel Haynes. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- Edward W. Clay and "Life in Philadelphia" in "Reframing the Color Line: Race and the Visual Culture of the Atlantic World." (Exhibit by the Wlliam L. Clements Library, The University of Michigan)

- Liberia; Or Mr. Peyton's Experiments (Digital Text, Indiana University Library)

- "Black Founders: The Free Black Community in the Early Republic" (Exhibit by the Library Company of Philadelphia)