Musical Instrument Making

By Lisa Minardi

Essay

Philadelphia became the leading center of musical instrument making in colonial America and the early republic, reflecting the importance of music in everyday life. Early Philadelphia’s many German inhabitants, unlike the Quakers, openly embraced both secular and sacred music. Philadelphia became particularly noted for producing keyboard instruments and dominated American piano manufacturing from 1775 until surpassed by New York and Boston in the 1830s. Musical instruments continued to be made in Philadelphia, however, most notably pianos. Smaller cities such as Lancaster, Reading, and Harrisburg also became home to musical instrument makers by the late eighteenth century. In 1839, the town of Nazareth, Pennsylvania, became the headquarters of the C.F. Martin & Company, which continued to be a global leader in the manufacture of acoustic guitars in the twenty-first century.

Moravian craftsmen who immigrated to colonial Philadelphia brought their skills as makers of instruments, from church organs to stringed instruments. One of the first keyboard instrument makers in the colonies, Johann Gottlob Klemm (1690–1762), immigrated to Philadelphia in 1733. Six years later, he made and signed a spinet, the earliest known American-made keyboard instrument. That same year Klemm completed an organ for the Swedish Lutheran Church (Gloria Dei) of Philadelphia.

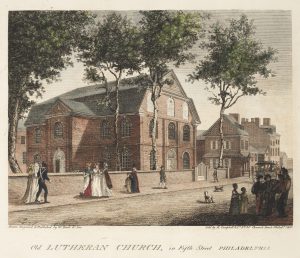

With music an expected part of both Moravian and Lutheran worship, their churches were among the first to acquire organs. St. Michael’s Lutheran Church of Philadelphia dedicated an organ imported from Germany in 1751. By comparison Christ Church (an Anglican congregation) acquired an organ in 1728 from Ludwig Christian Sprogel (1683–1729), but it had failed by 1739 and the congregation did not acquire a new organ—built by Moravian craftsman Philip Feyring (1730–67) —until 1766. St. Joseph’s Roman Catholic Church, which had numerous German members, also had an organ by 1748. Klemm also worked with the Swedish émigré Gustavus Hesselius (1682–1755), a painter, on an organ commission for the Moravian Church in Bethlehem. In addition to the Moravians, English instrument-maker Dr. Christopher Witt (1675–1765), who joined a German Pietist group of Mystics living along the Wissahickon Creek in 1704, sold an organ, possibly one that he had built, to St. Michael’s Lutheran Church in Germantown in 1742.

Stringed instruments made by John Antes (1740–1811), a Moravian composer and instrument maker in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, included three examples that survived in museums and private collections: a violin dated 1759, a cello dated 1763, and a viola dated 1764. Among brass instruments, trombones had special meaning for Moravians as the instrument named in Luther’s German translation of the Bible as accompanying the word of God. Trombones typically came from Europe, however, because of the scarcity of sizable quantities of brass in the colonies.

Skills of the Instrument Maker

The making of keyboard instruments, essentially a highly specialized area of furniture production (joinery), required both technical expertise and detailed knowledge of many wood species. For example, mitered dovetail joints typically concealed all evidence of the joinery in a piano frame, which was usually built of solid mahogany to withstand the enormous strain exerted by the tension of the strings. Many instrument makers first trained as joiners and later specialized in building instruments. Both Klemm and his protégé David Tannenberg (1728–1804) worked initially as joiners before taking up instrument making. With nearly fifty organs to his credit, Tannenberg became the most renowned organ builder in early America. Keyboard instruments were complicated to build; a large organ could take a year or more to finish, while a piano might take one hundred or more working days depending on its complexity.

Most keyboard instruments in colonial American homes were in the harpsichord family, in which the strings are plucked. Their volume and tone could only be varied in limited fashion. By the late 1700s, pianos surpassed harpsichords. Distinguished by the use of small hammers that strike the strings, a piano’s sound is controlled by varying the pressure on the keys. The earliest known reference to a piano made in America appeared in Philadelphia in 1775 when Johann Michael Behrent (?-1780) announced that he had “just finished for sale, an extraordinary instrument, by the name of PIANOFORTE, of Mohogany, in the manner of an harpsichord, with hammers.”

Charles Albrecht (c. 1760–1848), a German, immigrated to Philadelphia in the mid-1780s and worked as a joiner. By 1789, his work included a mahogany piano later preserved in the collections of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania and Philadelphia History Museum at the Atwater Kent—the oldest known American-made piano. In 1792, Albrecht offered for sale “TWO new and elegant PIANO FORTES which he will warrant to be good.” By 1798, Albrecht’s shop made at least ninety-three pianos, more than twenty of which survived into the twenty-first century. Later examples feature gilded and painted floral decoration on the nameboards, likely made by an ornamental painter. Albrecht employed numerous apprentices and journeymen, including Joshua Baker (b. 1773) and Charles Deal (b. 1793), but he also advertised pianos imported from London in 1799, 1800, and 1802. His brother, George Albrecht (?-1802), also made pianos in Philadelphia and Baltimore.

By the 1790s instrument makers working in Philadelphia included the Scottish immigrant Charles Taws (c. 1742–1836), who moved to the city from New York. Taws began advertising in 1790, when he offered for sale “of his own manufacture, a few elegant and well toned Piano Fortes.” Listed in the Philadelphia city directories first as an “organ builder” and in subsequent years as a musical instrument maker, in 1793 Taws advertised his pianos as “superior to any imported” from London or Dublin. By 1805, however, Taws began advertising imported London pianos, which he praised as superior to local products, and in 1813 he derided “HOME MADE instruments.” Given the limited market for pianos, touting imported models as less expensive and of higher quality than locally made ones was evidently advantageous for business owners such as Albrecht, Taws, and others.

Beyond Philadelphia

Instrument makers also worked in smaller urban centers and towns outside of Philadelphia, including Wilmington, Delaware, and Lancaster, New Holland, Shaefferstown, Reading, and Nazareth in Pennsylvania. In 1839, the German émigré guitar maker Christian Frederick Martin (1796–1873) relocated his six-year-old business from New York City to Nazareth. An early Moravian settlement founded in 1740, Nazareth remained the headquarters and principal factory location for the C.F. Martin & Company into the twenty-first century.

Philadelphia dominated the American piano trade in the early nineteenth century, and in 1830 could boast of eighty piano makers. Skilled instrument makers included new influxes of German immigrants, among them Christian Frederick Lewis Albrecht (1788–1843), who in 1823 opened a shop in Philadelphia (no connection between him and Charles Albrecht is known). During the 1820s, the company known as Loud & Brothers, started by London immigrant Thomas Loud Evenden (1792–1866) and family members, led the local piano industry. In 1824 alone, the firm made an astonishing 680 pianos at its Philadelphia manufactory on Chestnut Street. By 1831 Loud & Brothers also made upright pianos. As the nineteenth century progressed, the company also made the pump organs that became a staple element of genteel Victorian parlors.

Philadelphia soon lost ground to New York and Boston, however. In 1829, approximately 2,500 pianos were built in the United States: Philadelphia made the largest number, nine hundred, followed by eight hundred made in New York and seven hundred in Boston. The locus of the piano industry shifted with the emergence of major manufacturers in Philadelphia’s rival cities. In New York, German immigrant Heinrich Engelhard Steinweg (1797–1871) founded Steinway & Sons in 1853. Boston also became a major production center, led by Alpheus Babcock (1785–1842), who moved there from Philadelphia in 1837.

On a gradually smaller scale, Philadelphia continued to produce pianos. C.F.L. Albrecht’s company lived on after his death in 1843 and in 1887 was acquired by Blasius & Sons; they continued to make pianos into the 1920s. Other major firms included the Philadelphia Piano Manufacturing Company of Hunt, Felton & Co., which operated by the 1850s at 211 N. Third Street. In 1891, Irish émigré Patrick J. Cunningham (?–1941) founded the Cunningham Piano Company, with a factory at Fiftieth and Parkside Avenue and show room at Eleventh and Chestnut Streets. After thriving for several decades, the company ceased production in the 1930s when demand for luxury pianos plummeted during the Depression. After World War II, Louis Cohen, a former employee, bought the company and relocated it to Germantown. There, the business focused on piano restoration rather than manufacture. In 2000 Cunningham resumed selling new pianos, assembled in China from parts made in Italy, Japan, Germany, and other countries.

After piano manufacturing declined in the 1900s, particularly during the Depression era, some Philadelphia companies developed a new niche in the restoration of musical instruments. Others became importers of foreign-made musical instruments. These businesses remained in the twenty-first century as the remnants of Philadelphia’s once-leading role in the production of American musical instruments.

Lisa Minardi is executive director of Historic Trappe and the Lutheran Archives Center at Philadelphia. She is a Ph.D. candidate in the History of American Civilization program at the University of Delaware, where she is studying the German community of early Philadelphia for her dissertation. Her publications include numerous books and articles on Pennsylvania furniture, architecture, and folk art. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2020, Rutgers University