Omnibuses

By John Hepp

Essay

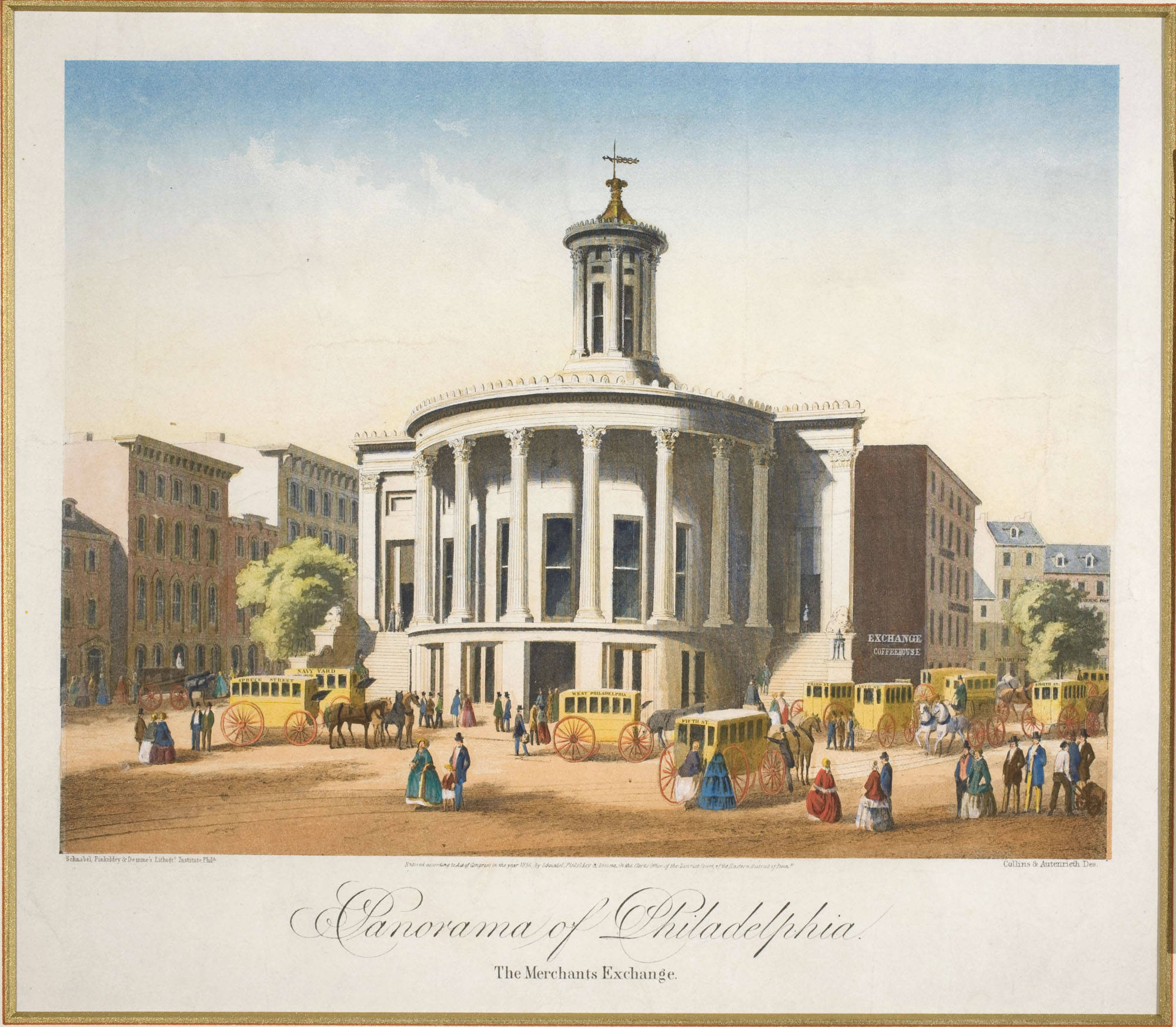

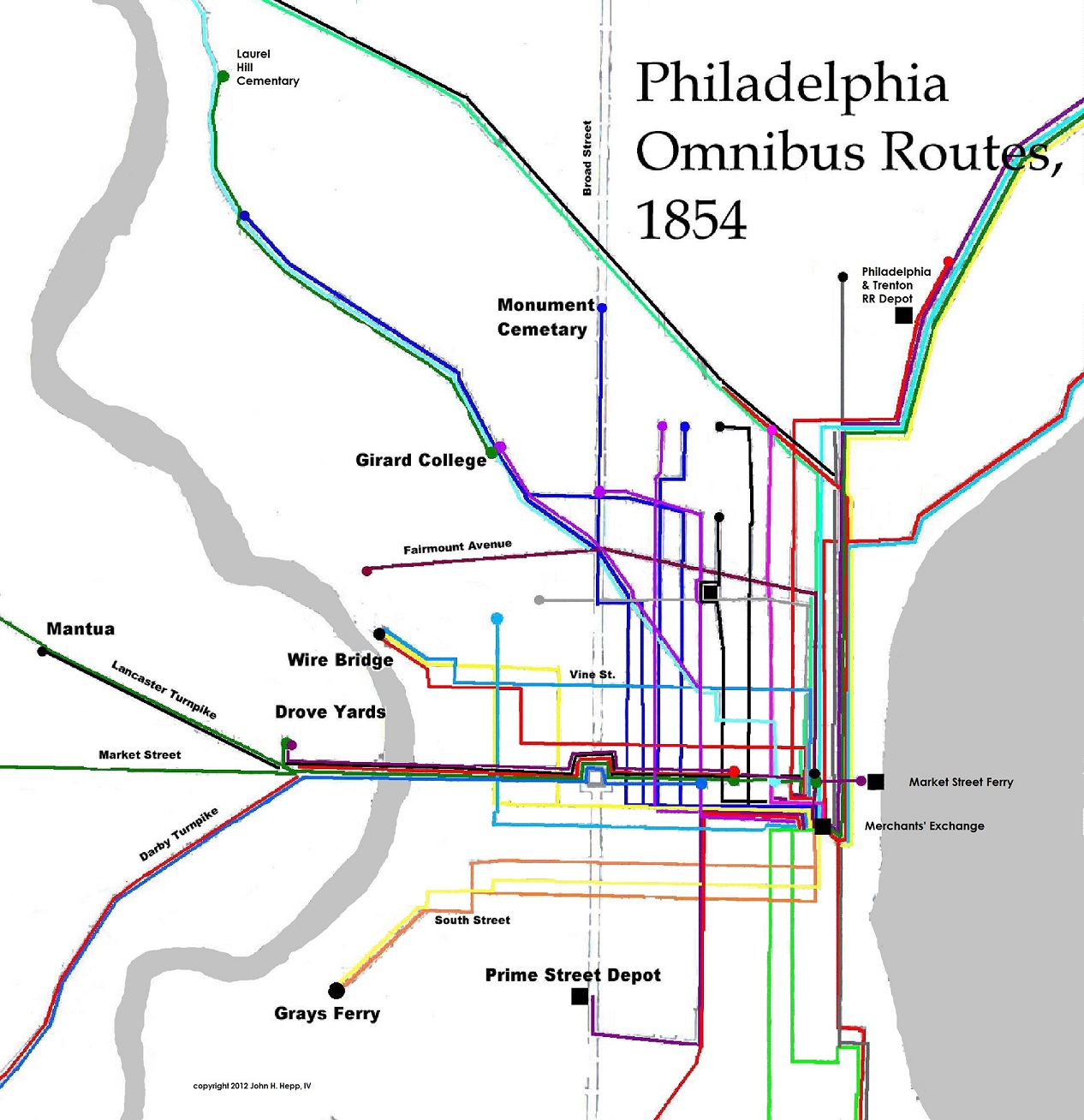

One of the earliest forms of public transportation in Philadelphia (and its early suburbs prior to the 1854 consolidation of the city with the county) was the horse-drawn omnibus introduced in 1831. The omnibus, together with the railroad, created the first urban commuters and it effectively became the model for all future street-based public transportation development in Philadelphia.

The omnibus was both a concept and a technology. As a concept, it was simply a short-distance version of the stage coach that operated on fixed routes, for fixed fares, and without the need for advance reservations. As a technology, the omnibus was a new form of horse-drawn vehicle that allowed for more rapid ingress and egress of passengers. Although the omnibus was “public transit” (in the sense it was shared), its relatively high fares precluded it from being “mass transit” and the majority of riders in Philadelphia and elsewhere were members of the middle classes and above. Omnibus riders were primarily business owners and senior “clerks” (salaried workers), whose firms were located in the central business district (then centered on Second and Third Streets) and who lived in Southwark, the Northern Liberties, and western Philadelphia. Along with similar people who used the early commuter trains, these were the first Philadelphians who could separate home from work by any appreciable distance.

Concept Imported From Paris

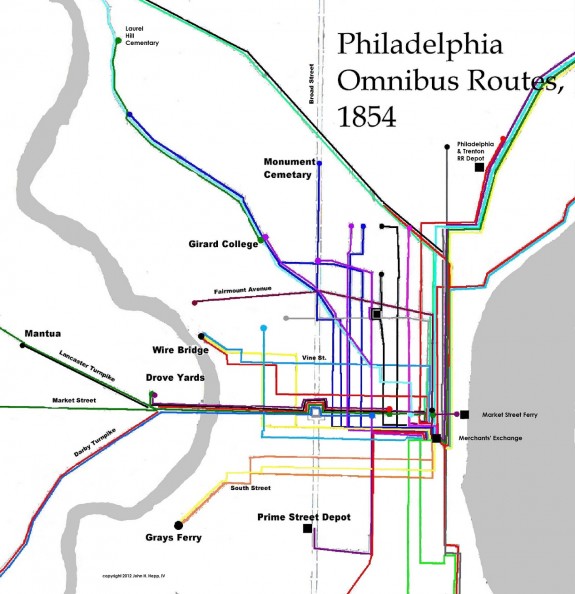

By 1830, the population of the city and its adjoining suburbs in the county was well in excess of 130,000 and it was the second largest metropolitan area in the country after New York. As the population expanded northward, westward and southward from the city’s original center along the Delaware River at Market Street, entrepreneurs imported the concept of the omnibus from Paris (where it originated in 1819 and the name was coined in 1828), New York (1827) and London (1829). James Boxall opened the first route in December 1831 on Chestnut Street between Second Street and Schuylkill Seventh Street (modern Sixteenth Street). The service operated hourly and charged a fare of ten cents. From this modest start, omnibus service quickly expanded throughout the city and its immediately adjoining suburbs. By the late 1850s over three hundred omnibuses operated over dozens of routes on a regular basis. While fares remained high on many routes (commonly ten or twelve cents), some shorter routes charged lower fares (as little as three cents per trip) and most lines offered annual “subscriptions” (or season tickets) to regular commuters.

Based on evidence primarily drawn from New York, most historians have assumed that the unregulated omnibuses functioned in a rather wildcat manner; the little surviving evidence from Philadelphia in the 1850s, however, indicates a more regular and self-regulated operation with fixed routes on parallel streets. In 1855, the city imposed an annual tax on vehicles used as omnibuses and as this tax nicely coincides with the introduction of street railways in 1858, it allows the tracking of the omnibuses’ decline. In 1857, there were 322 omnibuses taxed in the city, by 1859, this had fallen to 59, and reached a mere one by 1864. The day of the horse-drawn streetcar had arrived. The rails of the streetcars allowed for smoother and faster transport with fewer horses and the new technology rapidly replaced the old omnibus as the primary means of transport on most streets.

John Hepp is associate professor of history at Wilkes University in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, and he teaches American urban and cultural history with an emphasis on the period 1800 to 1940. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2012, Rutgers University.