Phrenology

By Shu Wan

Essay

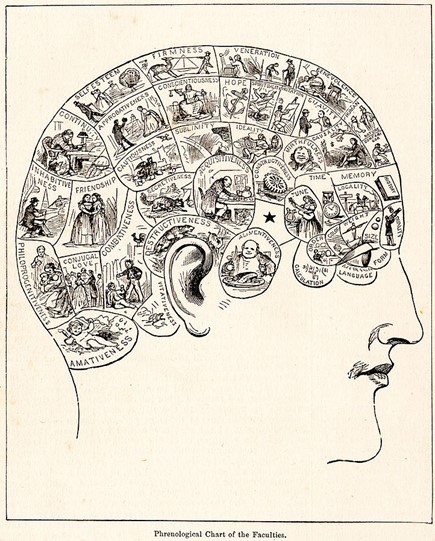

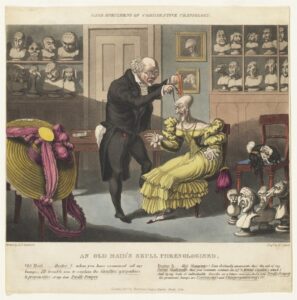

Although later regarded as a pseudoscience grounded on racism and racial discrimination, phrenology initially represented an emerging science of investigating individuals’ intellectual capacity and mental faculty based upon the physical features of their skulls and brains. Originated in Europe at the end of the eighteenth century, phrenology came to Philadelphia as a new science in the first half of the nineteenth century and found promoters among local physicians and scientists.

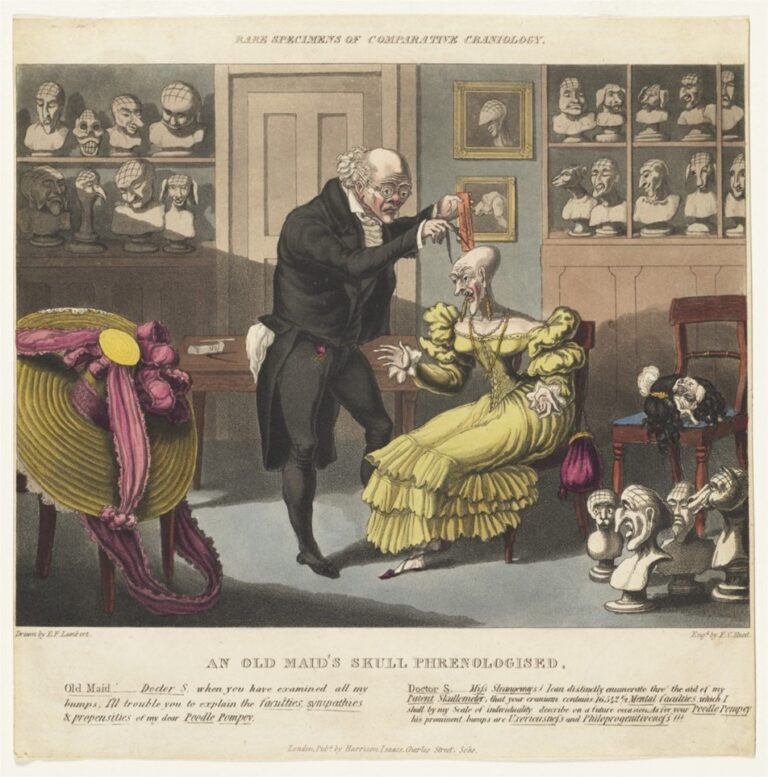

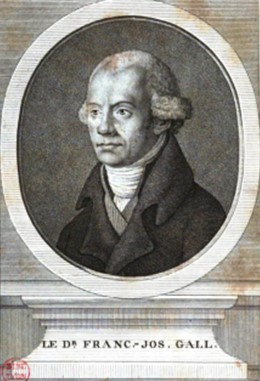

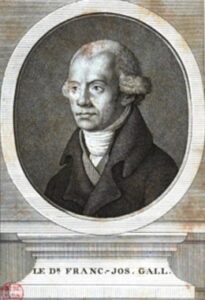

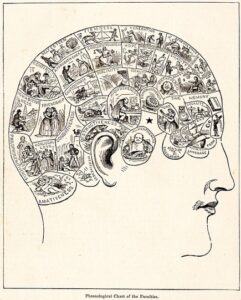

In 1796, the German physician Franz Joseph Gall (1758–1828) created the prototype of phrenology. He argued that human beings’ different mental faculties were embodied in the shape and size of specific parts of brains and skulls. Following Gall, his collaborator Johann Gaspar Spurzheim (1776-1832) created and popularized the term “phrenology” in reference to the research regarding human brains and skulls initiated by Gall across the world in the early nineteenth century.

Philadelphia-based physicians formed the first professional society and journal in the United States dedicated to phrenology in the 1820s. Two pioneering phrenologists, Charles Caldwell (1772-1853) and John Bell (1796-1872), founded the Central Phrenological Society of Philadelphia in 1822. This society also promoted and popularized phrenological knowledge through its affiliated magazine, American Journal of Phrenology, the first and leading phrenological journal in the antebellum United States. Despite this early activity, Boston and New York became more prominent strongholds of phrenologists, in part through the enterprise of brothers Lorenzo Niles Fowler (1811–96) and Orson Squire Fowler (1809–87), who established the New York-based publishing firm Fowlers & Wells Inc. to produce pamphlets and magazines promoting recent development in phrenology.

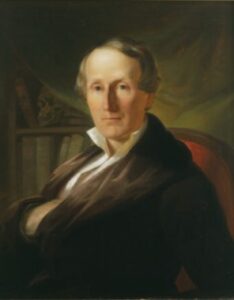

The popularization of phrenology in Philadelphia came with the 1839 American lecture tour by prominent Edinburgh-based phrenologist and physician George Combe (1788-1858). More than five hundred people came to see him in Philadelphia, many more than in New York City or Boston. His lectures fostered a mania for studying human brains and skulls for scientific purposes. As a result, additional Philadelphia-based physicians and academic institutions became attracted to the enterprise of phrenology, including Samuel George Morton (1799-1851), author of Crania Americana (1839), and his colleagues at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (founded in 1812). In the name of “natural science,” Morton integrated phrenology into the scope of science rather than pseudoscience.

Under Morton’s leadership, promoting a mix of phrenology and craniology became part of the academy’s mission. In contrast to mainstream phrenologists who focused on investigating how shape and size of brains corresponded to mental capacities, Morton and his colleagues attempted to apply phrenetical theory in craniology (the study of the skull to compare racial differences). In Crania Americana, Morton recommended his peers take the phrenological methodology into account when investigating human skulls for racial differences embodied by physical features then believed to reflect the superiority of the Caucasian in intellectual capacity to other races.

Morton’s next significant academic publication, Catalogue of Skulls (1849), represented his achievement in collecting and preserving human skulls in Philadelphia. Crania of different races across the world, including Native American groups, were recorded in the collection inventory of the academy. Following Morton’s steps, his colleague James Aitken Meigs (1829-1879) published and expanded the inventory in 1857, with the title Catalogue of Human Crania in the Collection of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. The expanding collection of human remains at the academy focused phrenology in Philadelphia on racial classification and categorization.

Phrenology declined in Philadelphia and elsewhere following the Civil War, after the height of pro-slavery arguments based on racial inferiority. The emerging anatomic knowledge and scientific measurements of human bodies gradually replaced phrenology in producing knowledge regarding human skulls. The Morton Cranial Collection became part of the collections of the University of Pennsylvania Museum, which in 2020 began a process for repatriation or reburial of the remains.

Shu Wan earned MA and MLIS degrees at the University of Iowa and has matriculated as a doctoral student at the University of Buffalo. His research interests focused on the history of disability in East Asia and North America. He also served as a research fellow in the Research Center for Social History of Medicine at Shaanxi Normal University in China and a book review editor in multiple academic journals in China, including World History Studies and Journal of the History of Social Medicine. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2022, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Links

- Morton Cranial Collection

- The Constitution of Man (1828) by George Combe

- Crania Americana by Samuel George Morton

- A System of Phrenology by George Combe

- Catalogue of Skulls of Man and the Inferior Animals: A Collection of Samuel George Morton

- The "New Science of the Mind" and the Philadelphia Physicians in the Early 1800's