Playgrounds

By Deborah Shine Valentine | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

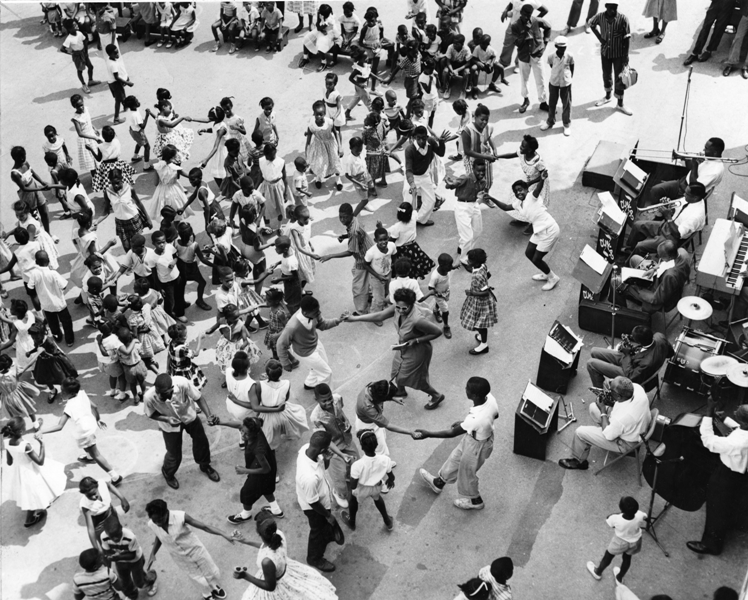

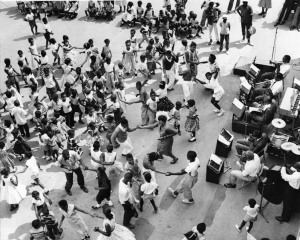

Beginning in the late nineteenth century, children’s play became an important concern of urban reformers, who regarded playgrounds—outdoor environments designed, equipped, and sometimes staffed, to facilitate children’s play—as essential components in shaping behavior and ordering urban space. Many public and semipublic playgrounds established as a result of their efforts became permanent features of the Philadelphia landscape, and were (and remain) deeply valued by residents and city leaders.

Philadelphia’s earliest playground advocates were groundbreaking leaders in what became known as the American Playground Movement. Nationally, the movement was institutionalized in 1906 when the Playgrounds Association of America (PAA)—later, the Recreation Association of America—formed. One of many Progressive Era child-saving reforms, the playground movement was a response to a variety of problems that resulted from rapid immigration, industrialization, and urbanization. At the same time, new theories in child psychology, education, and medicine claimed that play was essential to child development. The impact of these combined forces linked play to childhood in unprecedented ways. Key players (in the movement and on playgrounds) changed over time as the field of recreation professionalized nationally and locally, but goals connected to making the city a place that nourished healthy, happy, and productive citizens remained a core value for proponents of these spaces and programs, whether they were wealthy philanthropists, idealistic reformers, professional educators, or neighborhood residents.

Historians have commonly viewed Boston as the place where the American Playground Movement originated when, in 1885, reformers dumped a few piles of sand outside of the Parameter Street Chapel and West End Nursery to facilitate young children’s play. However, the establishment of Starr Garden Park—the seed of what would become Philadelphia’s first municipal playground and recreation center—in 1882 demonstrates that Philadelphia was also a forerunner in the playground movement. Locally, members of the City Parks Association (est. 1888), the Civic Club (a women’s club, est. 1894), the Philadelphia College Settlement (est. 1892), and the Philadelphia Board of Education all established playgrounds well before 1906. Nineteenth-century precedents for the design and construction of twentieth-century playgrounds included a few American versions of German outdoor gymnasiums and designated play spaces within large urban parks, such as the Children’s Quarters in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park (est. 1888) as well as outdoor playgrounds affiliated with day nurseries (early childcare facilities), kindergartens, and schools. One of these was Starr Garden, which was created in conjunction with a free kindergarten program.

For Progressives, effective playgrounds were not just spaces with a few swings and slides, but places where equipment was complemented by professionally designed programs in which children were taught “how to play.” This definition, though prevalent among reformers for several decades, was never accepted by the general public. Playgrounds more typically have been defined primarily as physical spaces, not programs, and by the mid-twentieth century three main types of playgrounds had become commonplace: community playgrounds, located in residential neighborhoods; school-yard playgrounds, affiliated directly with educational institutions; and “destination playgrounds,” impressive, multi-acre properties often situated on the edges of city limits that were in some ways sanitized versions of increasingly popular commercial amusement parks like New York’s Coney Island. The Philadelphia region had all three types.

Community and School-Yard Playgrounds

In a pattern that became typical in the early twentieth-century playground movement, philanthropists established Starr Garden in a “slum” neighborhood, where children would otherwise be forced to play in cramped apartments or on city streets. Initially located on a tiny lot on a back-alley street (St. Mary Street, now Rodman, between Sixth and Seventh), under the leadership of several privately funded organizations—the St. Mary Street Library (est. 1884), the Philadelphia College Settlement (est. 1892), and the Starr Centre Association (est. 1900)—Starr Garden expanded through the condemnation and demolition of nearby homes and buildings, a common method of playground development. By 1905, when philanthropist Susan Wharton (1852-1928) and other associates of the Starr Centre Association claimed Starr Garden as “Philadelphia’s first real playground,” it encompassed an entire city block. The Starr Center directors transferred control to the Playgrounds Association of Philadelphia (est. 1907) and then to municipal control under the Philadelphia Bureau of Recreation (est. 1911). In comparison to other early playgrounds, Starr Garden’s equipment was typical as well. Initially, it included swings and a place for playing ball; later, a sandbox and gymnastics equipment. When it became the Starr Garden Municipal Recreation Center on July 7, 1911, it gained a state-of-the-art recreation building and outdoor wading pool.

Less typical, but historically significant, the lot was situated near two institutions of great importance to black Philadelphians: the James Forten School (Sixth and Lombard, northwest corner), named for the prominent African American sailmaker and abolitionist, and Mother Bethel A.M.E Church (Sixth and Lombard, northeast corner). In 1882 several kindergarten advocates, including a white Quaker Anna Hallowell (1831-1905), Philadelphia’s first female school board member, and a black Episcopal priest, Rev. Henry Phillips (1847-1947), rector of the Church of the Crucifixion, encouraged Starr Garden’s namesake philanthropist Theodore Starr (1841-84) to transform a “trash heap” into a small park/playground to serve Philadelphia’s African American residents. Later, the Playground Association of Philadelphia (PAP) established a temporary play space, Coxe Playground (Eighteenth & Bainbridge), for African American children primarily. Despite this initiative, children of color remained generally underserved on playgrounds even after World War II when the PAA added a Colored Workers Bureau.

Alongside private investors, the Board of Education played a central role in Philadelphia’s playground movement. Beginning in 1894, leaders of the Philadelphia public schools, including later Pennsylvania governor Martin G. Brumbaugh (1862-1930), provided widespread support for the development of supervised “summer playgrounds” situated on public school grounds. The provision of outdoor space in affiliation with schools was not unusual, for the existence of school-yards in neighborhoods with little available open space was what made them so appealing to play advocates. What was new was the provision of planned activities, specialized equipment, and professional supervisors. With these changes, further supported by the integration of play-centered kindergarten programs and physical education into the public schools, the provision of play and play space for children outside of school hours became, to some extent, an accepted role of the school.

As the twentieth century progressed, neighborhood playground development in the Philadelphia region expanded into wealthy neighborhoods and suburbs, and movement leaders expanded their mission to include adults as well as children. Initially, both reformers and residents thought that playgrounds were unnecessary and even unwelcome in economically advantaged communities and that they might pose a threat to real estate values. In 1898, for example, attempts to transform Dickinson Square Park (Fourth and Tasker) into a playground were successfully thwarted by neighbors who preferred a more traditional park. The establishment of the Philadelphia Bureau of Recreation in 1911 (it became the Department of Recreation in 1952), however, demonstrated that residents and city authorities had accepted play and playgrounds as a public good. Locally and nationally the playground movement became the recreation movement. In addition to children’s playgrounds, recreation centers featured swimming pools, athletic fields, extensive programming, and recreation buildings open year-round.

Destination Playgrounds

Much larger and more remote than community playgrounds, the Philadelphia region’s earliest and most distinctive destination playgrounds were the Sanitarium Playground (nicknamed “Soupy Island”—a reflection of both its original location on Windmill Island in the Delaware River near the Benjamin Franklin Bridge and the soup served daily to those who attended) and the Smith Memorial Playground and Playhouse, located in Fairmount Park. Both were understood by their founders to be charitable entities, though they served very different populations initially.

Established in 1877, Soupy Island provided fresh air, nutritious food, medical care, and fun to poor, sick children from Philadelphia. The city’s plans to remove the island to allow better access for large ships combined with the limitations of the island space prompted a move to Red Bank, New Jersey, where managers purchased over eighty underdeveloped acres of land in 1887. From that summer until 1984, ferries transported children from Philadelphia to this location. Over the years attendance at Soupy Island expanded to include a wider range of children and families, including New Jersey residents. When the ferries stopped running, they arrived by bus or car. Soup continued to be served daily to all those in attendance. In 2007 the Campbell Soup Company provided support, donating soup and facilitating improvements to the property.

Philadelphia’s Smith Memorial Playground and Playhouse (the Children’s Playground and Playhouse in the Park) was founded by Richard Smith (1821-94), whose brother John F. Smith had donated one of the earliest boats for the Soupy Island project, and his wife Sarah A. Walker Smith (1826-95). It opened in 1899 on six acres in Fairmount Park. Designed for use by children aged ten and under and their caregivers, Smith was not limited to the poor, and there was no transportation provided. As a result, middle and upper-class families tended to dominate the space, including some well-to-do African American families. Thus, even during time periods when exclusionary admission practices were common in recreational settings across the region, Smith Playground served as one of the few places in the city where wealthy, working class, and poor residents of all races and religions might meet.

Funded through endowments and private donations, Soupy Island and Smith Playground avoided municipal control throughout the twentieth and into the twenty-first century. Soupy Island remained in the care of the Children’s Cruise and Playground Society and Smith Playground was supported primarily by private trusts until it was incorporated as a nonprofit in 2004.

Ebbs and Flows

The creation of playgrounds continued in the Philadelphia region, as elsewhere, into the twenty-first century, in urban and suburban neighborhoods, on small and large scales. Increasingly playgrounds were built to allow adults and children of all ages and abilities to play together, one of the most noteworthy being Jake’s Place, Cherry Hill (est. 2011), the first fully accessible playground in southern New Jersey. Spray parks replaced wading pools as a common water feature at playgrounds like Seger Park (Tenth and Lombard, Philadelphia) and Herron Park (250 Reed Street). Other unique destination playgrounds developed, including Kid’s Castle (est. 1996) in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, and the Camden Children’s Garden (est. 1999).

Like many city programs, public playgrounds were rarely fully funded or adequately staffed to meet the needs of residents. Thus, neighborhood playgrounds more often reflected demographic trends than shifted them. Community-led revitalizations are often connected to the gentrification of the surrounding neighborhood. In 2011, neighbors formed the Friends of Starr Garden in order to revitalize the neglected space, no longer situated in a slum, but in what had become known as Society Hill. Neighborhood residents also created new play spaces, as was the case with the volunteer-led effort to create Liberty Lands Park in the Northern Liberties neighborhood of Philadelphia in 1995. Unlike their nineteenth-century counterparts, in 2012, Dickinson Park neighbors aided and applauded the renovation and replacement of basketball courts and playground equipment by the city. The YMCA of Burlington and Camden Counties participated in the revitalization of the playground at Northgate Park in North Camden in 2012.

Historic preservation and playground support collided in 2012 around the revitalization of one of Philadelphia’s earliest playgrounds, Weccacoe. Initially championed by the Philadelphia College Settlement in the early 1900s, its improvement was delayed when research confirmed that it was located on a site of great importance to Philadelphia’s history, a nineteenth-century Bethel A.M.E. Church graveyard. It was not unusual for early playgrounds to be established on graveyards; like school-yards, these open spaces were often viewed by reformers as wasted land. However, given the particular significance of Bethel AME, this situation led to vexing questions about how to honor the value of the space as a community asset as well as the lives of those buried there.

Less impacted by changing demographics and purposes, aging destination playgrounds faced ongoing challenges as well. Both Soupy Island and Smith Playground deteriorated in the late twentieth century and required revitalization early in the twenty-first. The eight-level Doylestown Castle in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, closed due to safety concerns in early 2013 and required community financial support to avoid permanent closure.

Playgrounds did not solve Philadelphia’s social problems as many of their founders hoped they would, but they clearly had staying power. Perhaps in part because they have been symbols of idealistic visions of childhood and community, they could be the target of frustrations, as evidenced in incidents of arson and other forms of vandalism. Because they have been open spaces, they could leave users vulnerable to violence and provide gathering places for activities that tear down communities rather than build them up. Concerns about lawsuits related to playground injuries increasingly constrained playground design and use in the early twenty-first century. A perceived conflict between play and children’s academic progress left school-yards increasingly empty. Increased competition with more high-tech forms of entertainment posed a constant challenge for destination playgrounds. However, when both the city government and neighborhood residents invest in them, Philadelphia’s playgrounds have been and can be places that significantly improve the quality of urban life. It may be necessary to let go of idealized visions of playgrounds as magical spaces that can solve social problems, but it is hard to imagine greater Philadelphia without them.

Deborah Shine Valentine is assistant professor of Early Childhood Education at Saint Joseph’s University, Philadelphia. She received a Ph.D. in Childhood Studies from Rutgers-Camden (2013). She is currently working on a book manuscript that explores the history of playgrounds, race, and early childhood education in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Philadelphia.

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Caretakers emerge for Mt. Airy's Houston Playground (WHYY, March 1, 2013)

- Neighbors, school officials look to keep Houston's playground a community asset (WHYY, December 3, 2012)

- Torched Philly playground will rise from ashes with help of Eagles (WHYY, June 19, 2012)

- Neighbors look to save historic Wissahickon Playground from destruction (WHYY, March 5, 2015)

- Extending opportunity for fun, fitness to all at Philly parks and playgrounds (WHYY, August 24, 2016)

- Reimagining Mifflin Square Park in 21 languages (WHYY, October 5, 2016)

- Waterloo Playground's revival takes off with Urban Roots / MTWB support (WHYY, October 18, 2016)

- ‘Jake’s Law’ would nudge every N.J. county to build a playground accessible to all kids (WHYY, November 25, 2016)

- Designed for green play, a South Philly schoolyard wins recognition (WHYY, May 16, 2018)

- The push for playgrounds brings people together (WHYY Community Conversation, February 9, 2019)

Links

- Philadelphia Parks and Recreation

- City Parks Association

- Google Map Mashup of Philadelphia Playgrounds (Philadelphia Playground Project)

- Jefferson Square Park and Sacks Playground (PhilaPlace.org)

- Liberty Lands Park (PhilaPlace.org)

- Seger Park

- Weccacoe Playground Burial Ground Site Visit (Philadelphia Tribune)

- Soupy Island (PhilaPlace.org)

- Build the Kingdom at Kid's Castle (Doylestown, Pa.)

- Camden Children's Garden

- Jake's Place (Cherry Hill, N.J.)

- Playground Professionals