Prehistoric Native Peoples and Archaeology

Essay

For thousands of years before European settlement, Native Americans inhabited North America and left behind evidence of their lives in the form of artifacts, which archaeologists have studied and interpreted. The archaeological record for Philadelphia and the surrounding area reveals the complex relationship between prehistoric peoples and the region’s changing environment. Archaeologists also have learned how the earliest human inhabitants of the Delaware Valley interacted with other groups and with each other.

Interest in the prehistoric archaeology of the region started with the writings of Charles Conrad Abbott (1843-1919), a naturalist and archaeologist who discovered prehistoric remains on his farm outside Trenton, New Jersey, that appeared to be similar to Upper Paleolithic tools found in Europe. While they were not as old as that, Abbott’s writings in the 1880s and 1890s made Trenton and the surrounding region a hotbed of prehistoric archaeological activity. Scientists from Europe and New England came to the area to examine prehistoric objects. The University of Pennsylvania Museum of Science and Art (later renamed the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology) in Philadelphia later hired Abbott as a curator.

Numerous prehistoric sites along the Delaware River in the vicinity of Philadelphia became known through the work of other archaeologists, including Henry Mercer (1856-1930) of the University of Pennsylvania. In New Jersey, around the turn of the twentieth century the American Museum of Natural History and the New Jersey Geological Survey commissioned a statewide survey of prehistoric sites. The survey identified hundreds of sites, which the New Jersey State Museum and State Archaeologist Dorothy Cross (1906-72) examined in the 1930s.

Through the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, archaeologists continued to uncover evidence of prehistoric Native Americans at sites being prepared for construction of new buildings or highways. Major excavations recovered significant material from the sites of the SugarHouse Casino, the National Constitution Center, and along I-95 in Philadelphia. Prehistoric sites beneath parking lots, in alleyways, and under nearby highways have been found undisturbed and intact.

Archaeologists seek sites with “integrity,” which hold the promise of adding to knowledge about the past, and they classify information by geography and by time periods. Because the region encompasses a number of different physiographic (environmental) zones, prehistoric peoples had access to different types of waterways, stone, and other natural resources. The artifacts they left behind helped archaeologists understand which areas were best for different purposes such as procuring stone, hunting, or creating settlements. Based on observed changes in technology and radiocarbon-dating of artifacts, archaeologists have identified three distinct prehistoric time periods—Paleoindian, Archaic, and Woodland.

Paleoindian Period (13,000 BCE – 8000 BCE)

The environment of the region during this time was cold and wet with a variety of grasslands, deciduous forests, and boreal forests. Human inhabitants lived nomadic lives as they moved from site to site to hunt animals and fish and gather plants, nuts, and seeds.

Paleoindian sites occur throughout the region, although not many have been professionally excavated. Identified as base camps, quarry sites, or quarry reduction sites, most of these locations are not technically “sites” but isolated individual finds of the single-fluted stone points that define the period. About sixteen fluted points have been recorded in the region, but none in Philadelphia. If Paleoindian sites or artifacts existed within the city limits, they could still be buried under modern development.

The largest and well-excavated Paleoindian sites in the Delaware Valley, such as Shawnee-Minisink near Stroudsburg, Pennsylvania, showed evidence of fish remains in fire pits as well as seeds of local plants. This site was excavated in the mid-1970s by American University and then again by Temple University from 2003 to 2006. The Plenge site in Warren County, New Jersey, which has not been professionally excavated, was occupied throughout the Paleoindian period. A few Paleoindian points have been found at the Abbott Farm National Historic Landmark south of Trenton.

Archaic Period (8000 BCE – 1000 BCE)

Significant environmental and culture change occurred during the Archaic period. Initially, the region had grown warmer than the Paleoindian period, but remained cooler and drier than our modern climate. Primary vegetation included forests of mostly spruce, pine, and, later, hemlock trees. Water levels in the oceans, rivers, and streams had risen significantly due to the near complete melting of the Pleistocene era continental glaciers. As a result, new and different environments appeared and attracted many new plant and animal species. However, the temperature and humidity of the climate cycled up and down during the long Archaic period. Taking advantage of these new and diverse habitats, native peoples stayed longer at some locations during different seasons. The human population and interaction among groups increased. Archaeologists have recovered artifacts such as soapstone bowls on sites miles away from their place of origin. While these artifacts may have only traveled twenty to fifty miles from their source, they provide evidence of a trade and exchange system.

Many Archaic sites lie along the boundary of the Inner and Outer Coastal Plain in New Jersey and the Piedmont Upland in Pennsylvania, areas rich in plant and animal species. Additionally, a number of Archaic period sites have been identified in South Jersey close to the Delaware River, including the Raccoon Point site excavated in 1957 by Charlie Kier (1913-88) and Fred Calverley (1913-95) and Savich Farm, excavated in the 1960s by amateur archaeologist Richard Regensburg (b.1938). On the other side of the Delaware River, recent site excavations along the I-95 corridor and at Bartram’s Garden historical site have produced large Archaic period sites within the city of Philadelphia. The human inhabitants of these areas produced a great variety of projectile points from the stone available from outcrops, stream beds, and glacial outwash. Archaeological evidence also suggests that a notion of death and afterlife possibly developed in this era, indicated by findings of objects placed in burials. At the Koens-Crispin site in New Jersey, for example, a number of burials purposefully included a variety of finely crafted and ornamental nonutilitarian artifacts. Koens-Crispin was initially excavated in 1916 by archaeologists from the University of Pennsylvania and again in 1937 by the New Jersey State Museum.

Woodland Period (1000 BCE – 1600 CE)

Similar to the environment of the twenty-first century, the Woodland period was warm and dry with mixed forests of oak, hickory, and chestnut trees, together with many other deciduous species. By the end of this period, just before the arrival of Europeans, archaeologists have identified distinctive cultural groups of Native Americans with vocabulary that remained in use in later centuries: Passyunk, Manayunk, Tulpehocken, Wissahickon, and Moyamensing, among others.

Among the most significant advancements during the end of the Archaic period and beginning of the Woodland period was the introduction of ceramic pottery vessels, which allowed food to be stockpiled for use during hard winters and made it possible for native groups to settle in place for longer periods. Archaeologists also have identified small triangular points as evidence of the introduction of the bow and arrow toward the end of the Woodland period. Other, more exotic materials like copper beads, stone items from Ohio, or sharks’ teeth are traded and exchanged by prehistoric groups over long distances. Archaeologists examining these artifacts propose that trade and exchange operated with groups in the Midwest and Southeast for their presence. Shark teeth found along the coast of New Jersey and Delaware are seen as being traded to the Midwest to be used in burials. During the Middle Woodland period, this long-distance trade operation changes, and local native peoples are no longer trading in these objects.

A very important Late Woodland site was discovered in the early 1980s in Gloucester City, New Jersey, opposite Philadelphia. During construction of a nursing home, evidence of prehistoric artifacts stopped work on the project until salvage excavation could take place. Members of the Archaeological Society of New Jersey and later MAAR Inc. excavated human remains and refuse pits with pottery and charred food remains. Another site dating from the Late Woodland period, the Reeder’s Creek site on both sides of the Delaware River north of Trenton, excavated in 2011 by archaeologists with the firm AECOM, yielded pottery vessels and many stone tools. Baked residue inside the pottery helped archaeologists determine that the vessels were used to cook plants, although in most cases they were not able to identify what plants were used. In one sample, they found evidence of Typha (cattail) root.

The prehistoric archaeology of Greater Philadelphia has documented life before colonization and urban development. In the early twenty-first century, archaeologists continued to excavate sites not only within the city of Philadelphia but also across the Middle Atlantic region. From the Paleoindian to Woodland periods, native groups lived where we live, and as a result left behind artifacts that have hundreds if not thousands of years of stories to tell.

Gregory D. Lattanzi, Ph.D., is Assistant Curator at the Bureau of Archaeology & Ethnography at the New Jersey State Museum, Trenton, New Jersey. Lattanzi specializes in ancient copper working and pottery analysis in the Middle Atlantic region. He is also interested in trade, exchange, and the aspect of cultural complexity as they apply to native groups in the Middle Atlantic region.

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Archaeological Dig planned for Germantown Potter's Field Site (WHYY, October 26, 2012)

- Archaeological Dig for Germantown Potter's Field Site will not start before March 2013 (WHYY, January 25, 2013)

- Bringing in High-Tech Tools to Study the Artifacts of the Penn Museum (WHYY, October 18, 2014)

- Lavallette Beachcomber finds Prehistoric Projectile Point (WHYY, February 10, 2015)

Links

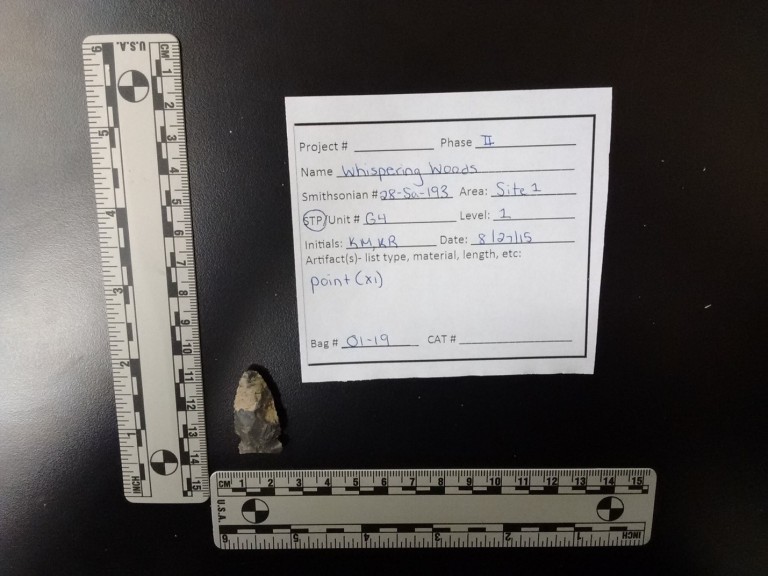

- Whispering Woods Archaeological Investigation (Rutgers-Camden)

- University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

- Dorothy Cross Jensen (New Jersey Archaeology Blog)

- Native American Archaeology (Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission)

- Society for Pennsylvania Archaeology

- The Indians of Pennsylvania (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Archaeological Society of New Jersey

- Archaeology and Archaeological Site Survey (New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection)

- National Museum of the American Indian (Smithsonian Institution)