University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (Penn Museum)

Essay

The Penn Museum—officially the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology—originated in 1887 through the combined efforts of university scholars, administrators, and Philadelphia philanthropists. Created as part of a broader movement to expand, modernize, and professionalize the university, throughout its history the museum also performed a public role of bringing ancient and far away cultures to Philadelphia for both academic research and spectacular display. Although always an independent entity, the museum also served the mission of the affiliated university through its roles in scholarly innovation, collegiate education, and outreach to the public. In the twenty-first century, as museums and the disciplines of archaeology and anthropology became more critical about the ways they represented nonwhite and non-Western cultures, the Penn Museum reconsidered the form and content of its dual academic and public roles.

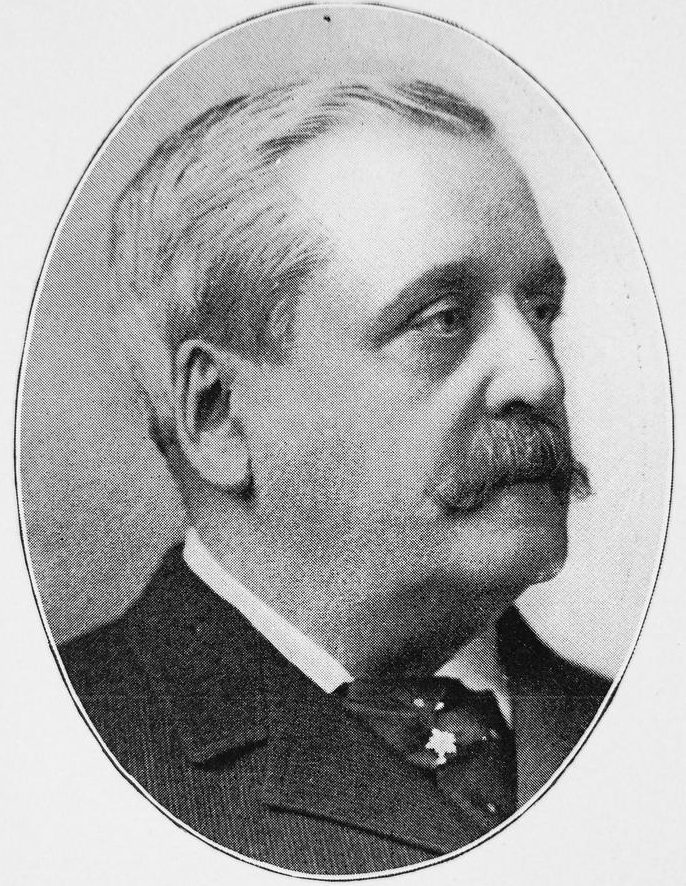

The idea for the museum originated in 1887, when John Punnett Peters (1852-1921), a professor of Hebrew at the University of Pennsylvania, persuaded University Provost William Pepper (1843-98) to fund an expedition to the Sumerian city of Nippur in modern-day Iraq. In agreeing to do so, Pepper stipulated that anything Peters collected would be held at the university in a new museum. The museum, the expedition, and the scholarship that resulted combined anthropology—the study of man, his origins, and the evolution of human culture—with archaeology, a field rooted in the search for evidence to verify Greek mythology, the Bible, and other founding myths of Western, Christian civilization.

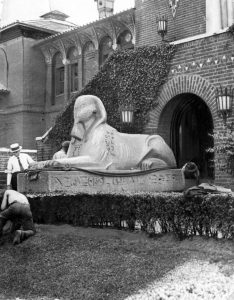

The museum created to house the fruits of the Sumerian expedition and other collections had its first home in the Furness Library on the university’s new West Philadelphia campus from 1890 until 1899. It then moved to its permanent home in a stylishly eclectic building designed by a team led by Wilson Eyre (1858-1944). Although the university held the collections and faculty members often led expeditions, funding for the museum and its collecting efforts came primarily from independent groups like the Babylonian Exploration Fund, the Egypt Exploration Society, and the University Archaeological Association. These organizations were usually headed by prominent, wealthy Philadelphia philanthropists who continued to be a key source of income throughout the museum’s history.

Museum’s Dual Purposes

The institution’s original name, the Free Museum of Art and Science, reflected its interdisciplinary and dual purposes. For researchers, the museum housed and displayed artifacts of human culture as scientific resources. At the time, anthropology and archaeology were not the interpretive, liberal arts fields that they later became, but were disciplines dedicated to systematic classification and scientific observation. However, while scholars and researchers used the collections for science, public displays also enriched the museum experience for visitors and allowed those who felt welcome to demonstrate their elite aesthetic taste. As was typical of endeavors in anthropology and archaeology, the museum sought to demonstrate both similarities and differences among diverse communities. Many cultures were collected under one roof, but their arrangement reinforced ideological hierarchies by presenting an inevitable march of human progress and creating contrasts between supposedly primitive crafts and civilized tastes. In Philadelphia, this was reflected in curatorial and architectural choices that saw ethnological artifacts collected from indigenous people arranged on the lowest floor and archaeological collections of Greek, Roman, and Babylonian civilizations on the floors above. It tied a literal, physical march from bottom to top to an intellectual and ideological one.

In 1913, the museum officially changed its name to the University Museum, a step in a gradual evolution of the institution’s relationship to the University of Pennsylvania and a sign of the shifting composition of the Board of Managers. The university always housed the collections, making them available to staff and students for teaching and research, but the museum operated independently. Curators and leaders of expeditions sometimes, but not always, had appointments as faculty members, and likewise the Department of Anthropology sometimes, but not always, operated out of the museum. Although officially separate, administrative control over museum matters like hiring and firing shifted to the university in the early twentieth century—coinciding with the name change. Financial contributions from the university began in the 1930s, and by the 1980s Penn exclusively appointed the museum’s Board of Overseers. While administrative and financial control shifted, the hybrid public-academic nature of the museum remained constant throughout its history..

In the first half of the twentieth century, as the museum and the fields of anthropology, ethnology, and archaeology grew, so did the museum. Ethnographic expeditions, excavations of ancient artifacts, and acquisitions through purchase grew the collections and programs of research and display. While the research had academic value, these exotic objects also came from areas of the world that were colonized by Western empires—and thus were embedded in problematic politics recognized only later by most American curators and scholars. Those politics periodically came to the fore, especially during the breakup of empires in the mid-twentieth century. In Latin America, where the museum conducted work throughout the twentieth century, local interest in heritage, tourist dollars, and the struggle for post-colonial power drove governments to control archaeological research more tightly over time. This impacted the intellectual trajectories of anthropology and archaeology, and it led expeditions like those of the University Museum to become somewhat more collaborative.

The Louis Shotridge Era

In the 1920s and 1930s, one of the most important curators at the museum—although never a professor at the university—was Louis Shotridge (1882-1935), a Tlingit Indian from the Pacific Northwest. Conducting salvage ethnographies, Shotridge collected and documented languages and traditions at risk of being destroyed by settler colonialism and government policies that criminalized indigenous culture and decimated native populations. On the one hand, Shotridge assured that some part of indigenous culture—in some cases his own culture—would survive. On the other hand, he knew the institution where he worked took sacred objects and sterilized them, that it interpreted indigenous people as primitive savages, and that it expected nonwhite scholars like himself to assimilate themselves and their scholarship into the authoritative voice of academic institutions.

After World War II, old tensions between white, Western scholars and post-colonial or third-world nations arose, but they were sometimes addressed in new ways. Research continued to be largely generated and validated by elite European and American institutions with systems of knowledge and hierarchical classification that changed little from the nineteenth century, but museums also became more dedicated to leaving artifacts in their places of origin so they might be interpreted and appreciated by the communities from which they came as well as being used in scholarship.

At the same time, the black market for antiquities, fostered by the poverty of so-called third world nations and by the exploding value of artifacts in commercial markets, also challenged museums in the post-World War II era. In 1970, the University Museum under director Froelich Rainey (1907-92) influenced acquisitions policies throughout the museum field by issuing the Pennsylvania Declaration, which pledged to end the purchase of artifacts without “a pedigree—that is information about the different owners of the objects, place of origin, legality of export, and other data useful in each individual case.” The statement called attention to the complex question of ownership: Was the object obtained “legally” or was there proof that it had been looted? Ultimately, in addition to restricting new acquisitions, the museum returned objects to countries including Italy, Turkey, and Peru. In 2008, the museum created the Penn Cultural Heritage Center to address related issues.

Repatriating Collected Objects

The U.S. Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) enacted in 1990 provided the most effective and widely enforced mechanism to address the concerns of indigenous people in the United States with regard to cultural heritage. For the University Museum, between 1990 and 2016, this federal law led to twenty-five tribes successfully filing claims to have human remains and other religious objects returned to them from the museum’s collections.

The University Museum—which by 1996 was rebranded as the Penn Museum to make its institutional affiliation clearer—also confronted the complex issues of who should tell the stories of objects on display. Historically, Western museums presented narratives of hierarchical evolution and inevitable progress that either demonstrated continuities between ancient and modern societies or juxtaposed “primitive” and “civilized” cultures in ways that justified colonialism and racism. By the twenty-first century, however, museums like Penn’s sought to generate more understanding and appreciation of diversity and inclusion even though white, Western academic standards of science and objectivity tended to remain the arbiters of knowledge and worth.

In 2014, a reimagining of the Penn Museum’s North American gallery caught up with trends toward sharing authority for exhibit development with indigenous people. “Native American Voices” challenged old, racist narratives by representing native people as alive and thriving while also acknowledging how American and European colonialism decimated these communities and their cultures. For this exhibit, museum curators consulted with indigenous leaders, which resulted in a richer, more multivocal, and inclusive exhibit. Nevertheless, the museum clearly retained authority.

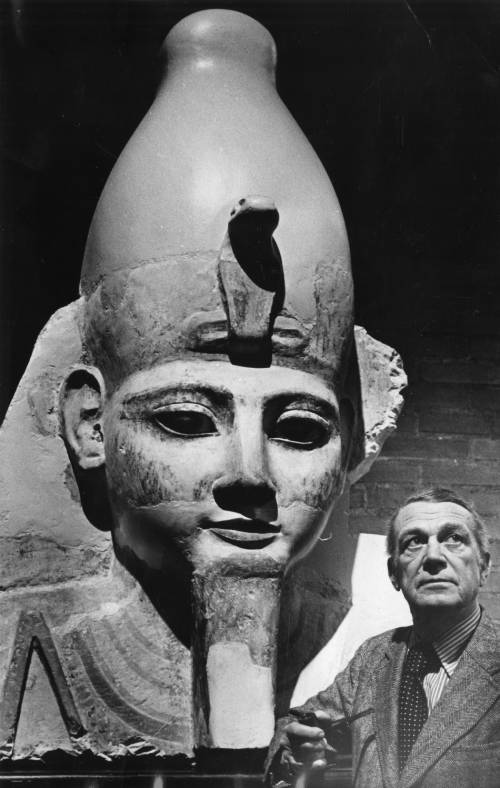

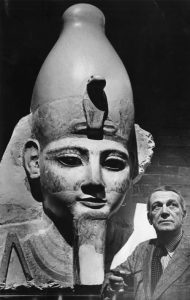

Other exhibit strategies focused on bringing more diverse voices and more relevant themes into the museum’s interpretation of its archaeological collections. Reinstalled Middle East galleries opened in 2018 with a focus on urbanization, and plans called for future renovations, restorations, and reinstallations of the Africa and Mesoamerica galleries, the Harrison Auditorium, and the Egyptian wing. A Global Guides program, initiated in 2018, incorporated the varied perspectives of contemporary Philadelphians who were immigrants and refugees from the areas of ancient cities excavated by the museum. Plans for renovation of the museum’s 1899 building, scheduled to continue through 2021, sought to create an increasingly visitor-centered institution with improvements including climate control, better way-finding, and more elevators.

In the twenty-first century, the Penn Museum faced the challenge of how to use old collections, many of which were collected in exploitative, colonial contexts, to tell new stories that incorporated communities and perspectives that the museum historically marginalized. Although hindered by its own history and the colonial history of its disciplines, new strategies were making this museum more engaged, and visitorship, especially for special events that showcased diverse cultural traditions, reflected that. William Pepper’s idea to create a museum that served both the university and the people of Philadelphia was being realized in new ways for a new era. Indeed, the institution whose mission was to explore “the human story: who we are and where we come from” was gradually and powerfully beginning to reassess who we are, who gets to speak for us, and where we get to do so.

Mabel Rosenheck is a writer, lecturer, and historian in Philadelphia. She received her Ph.D. in Media and Cultural Studies from Northwestern University and now works at the Wagner Free Institute of Science and elsewhere. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2019, Rutgers University