Prisons and Jails

By Annie Anderson | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

In the late 1700s, on the heels of the American Revolution, Philadelphia emerged as a national and international leader in prison reform and the transformation of criminal justice practices. More than any other community in early America, Philadelphia invested heavily in the intellectual and physical reconstruction of penal philosophies, and the region’s jails and prisons reflected these evolving principles. Throughout the 1800s, global and local observers looked to Philadelphia—particularly the Pennsylvania system of solitary confinement pioneered at Eastern State Penitentiary—as they modeled penal practices in their communities. By the late twentieth century, however, Philadelphia led the nation not in reform, but in rates of incarceration.

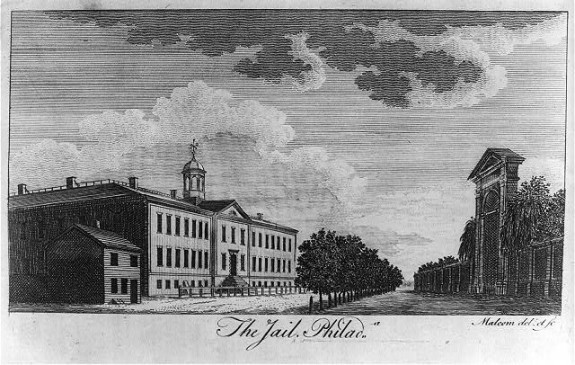

Local holding and correctional facilities—jails—emerged as the colonies’ populations grew and local economies developed. Philadelphia erected its first jail—essentially a well-fortified box-like room, seven feet by five feet—in late 1682 or early 1683 at the corner of Second and High (Market) Streets. Officials constructed a succession of several small jails in the near vicinity over the next forty years, including a brick prison, fourteen feet wide and twenty feet long, on High Street in 1695. A keeper lived in half of the building. A few years later, it was deemed inadequate. Around 1720, a stone prison and workhouse opened nearby on the corner of Third and High Streets. The prison portion of this facility housed debtors, runaway apprentices, and untried prisoners. The workhouse held those convicted of theft, vagrancy, and disorder.

Still, incarceration was used sparingly in colonial America. While criminal codes called for imprisonment for crimes such as bigamy and dueling, incarceration was typically reserved for those awaiting trial or sentencing. Penalties for those found guilty included fines or restitution, or corporal punishments such as branding or whipping. Capital punishment was meted out for a range of crimes, including blasphemy, kidnapping, and rape. As the colonies and their populations grew, officials made use of forts and blockhouses to house lawbreakers.

In Pennsylvania, William Penn (1644–1718) ushered in new legislation that reflected his Quaker values, including an almost total disavowal of capital punishment. In 1682, the province of Pennsylvania banned the death penalty for all crimes except murder and treason, while other colonies that emerged in the same era continued to enact much stricter criminal codes. Though Penn’s 1682 body of laws, known as the “Great Law,” included fewer capital offenses, it still demanded shameful corporal punishments and prison time: stealing livestock warranted thirty-nine lashes and banishment; swearing merited five shillings or five days in jail; sodomy and bestiality cost the forfeiture of one-third of one’s estate, whipping, and six months in the house of correction.

West Jersey Mirrors Pennsylvania

Criminal codes in the colonial province of Quaker-dominated West Jersey mirrored the milder punishments enacted in Pennsylvania, which varied sharply from the rigid codes of Puritanical East Jersey and New England. In West Jersey, criminal law protected the accused from undue punishments: no accused person could be convicted except by a jury of his neighbors, the accused could reject as many as thirty-five jurors before going to trial, and conviction could only occur upon the sworn testimony of two reputable witnesses. Still, corporal acts—whether the death penalty, branding, or whipping—encompassed nearly all punishments in East and West Jersey, which merged into a unified New Jersey in 1702. Because of the predilection for physical punishments, New Jersey had little need for penal institutions beyond small local jails, and there was no central prison administration during the colonial era.

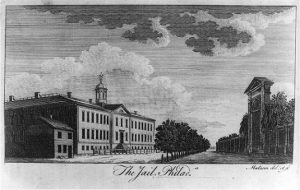

Overcrowding, corruption, violence, and bribery ran rampant in Philadelphia’s early jails. The stone prison earned the nickname “school for crime” and “seminary of vice.” Administrative control of the jail rested with the local sheriff, who extorted money from prisoners, sold liquor from a well-stocked bar, and withheld food and other necessary goods. Individuals—regardless of sex, age, or crime committed—mingled indiscriminately. Officials ordered the building of a new facility in 1773, and this “New Gaol,” known as the Walnut Street Jail, opened in 1776. The old stone jail closed in 1784 and was demolished the following year. Despite the larger quarters, the Walnut Street Jail hosted the same debauchery as previous jails. (The jail keeper operated a tavern in his previous job.) A 1787 grand jury reported that “the prison seems to them to be open, as to the general intercourse between the criminals of the different sexes; and that there is not even the appearance of decency.” Scandals plagued other local jails. Chester County’s house of correction, opened around 1725, was neglected within a few decades of its opening. An applicant for the position of jail keeper wrote: “the person last appointed [keeper] . . . having absconded from his residence therein . . . the workhouse has for a considerable time past been very ill kept.” Even as jails became attached to county courthouses—public facilities charged with the high-minded task of facilitating justice—the improprieties of local houses of correction continued into the 1800s. In 1888, the New Jersey State Board of Health condemned the Camden County Jail “as a disgrace to our common civilization and a menace to the health of the people.”

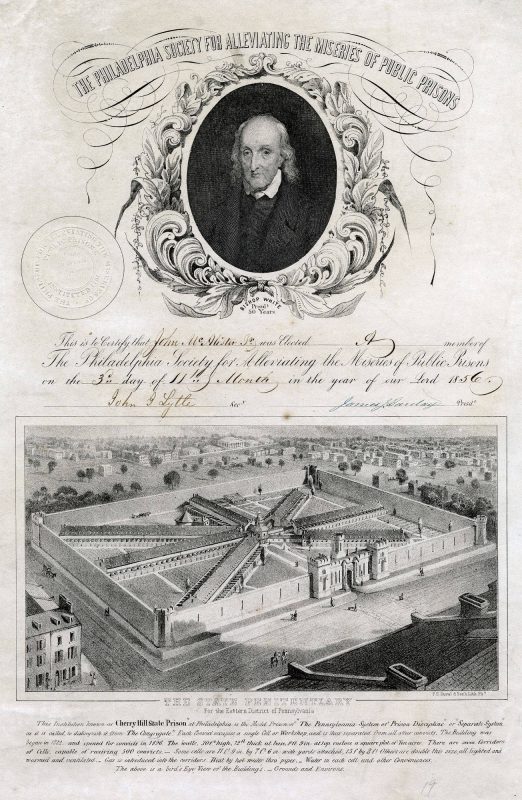

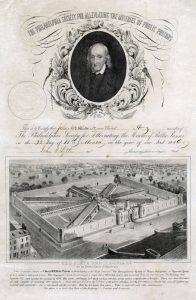

Prompted by the scandals of vice-ridden jails and the inhumanities of public punishment and spurred on by post-Enlightenment thinkers such as British prison reformer John Howard (1726–90), a group of prominent citizens formed the Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons (later renamed the Pennsylvania Prison Society) in 1787. The group, comprised of thirty-seven individuals from the city’s elite civic and political circles, including physician Benjamin Rush (1746–1813), politician Tench Coxe (1755–1824), statesman Benjamin Franklin (1706–90), and Episcopal bishop William White (1748–1836), advocated for prisoners’ rights, as well as the restructuring of correctional spaces. The Prison Society shunned a corrupt criminal legal system and grotesque public punishments in favor of a rational, humanistic—and newly private—correction of the spirit. The group drew on Howard’s ideas that safe and decent jail spaces—and thus, true rehabilitation—could only be ensured by segregation of individuals by class of offense. In April 1790, the society’s lobbying paid off: a new law mandated solitary confinement at the Walnut Street Jail and called for the erection of a new “penitentiary house” at the jail for “the purpose of confining therein the more hardened and atrocious offenders.”

Walnut Street Prison, the Country’s First

With this new law, the Walnut Street Jail became the Walnut Street Prison—the country’s first state prison. With this designation, the distinction between a jail and a prison became clearer: jails came to house individuals awaiting trial or sentencing, along with those convicted of misdemeanors, minor offenses that typically carry a sentence of one year or less, while prisons house individuals convicted of felonies, more serious crimes that demand longer sentences. The Walnut Street Prison incarcerated convicted offenders from every part of the commonwealth of Pennsylvania—a practice never before attempted in the fledgling United States. New Jersey soon followed suit. It began construction on its first state prison, in Trenton, in 1797 and opened it in 1799. The inscription over its front door read, in part: LABOR, SILENCE, PENITENCE, THIS PENITENTIARY HOUSE . . . THAT THOSE WHO ARE FEARED FOR THEIR CRIMES MAY LEARN TO FEAR THE LAWS AND BE USEFUL. Delaware did not establish a state penal facility until well into the twentieth century, opting instead to send adult offenders to county facilities. Though some regional correctional philosophies emerged, consistent penal practices across the colonies and in the early republic remained elusive.

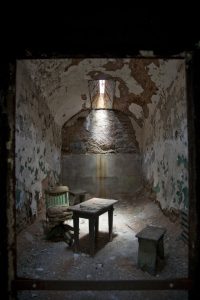

Untidy and experimental at first, Philadelphia’s prisons nearly perfected the separation of individuals in jails and prisons based on sex, age, and type of offense by the 1820s. The early experiment of solitary confinement at Walnut Street Jail inspired them to push for a prison where this penal practice could be implemented on a large scale. The first such prison, Eastern State Penitentiary admitted its first prisoner, Charles Williams (b. ca. 1809), in October 1829. Eastern State’s founders believed that in isolation, prisoners would reflect on their crimes and grow penitent; access their inner goodness and shun future criminal activity; and cease to corrupt or be corrupted by criminal associations in overcrowded jails. Prisoners spent twenty-three hours a day alone in their cells; they had two half-hour breaks for outdoor exercise in small yards attached to each cell. Prisoners ate, slept, and labored in their cells. Though internationally admired for its novel design and methodology, Eastern State’s use of solitary confinement drew criticism almost immediately after the prison opened. The British author Charles Dickens (1812–70), who visited Eastern State in 1842, claimed that prolonged isolation would inspire troubling mental health consequences. Outside observers found evidence of psychosis, anxiety, and depression among the prison population, but Eastern State officials remained vigilantly committed to the solitary system, at least publicly.

Eastern State’s architect, John Haviland (1792–1852), and the prison’s Quaker exponents wielded wide regional influence. Haviland was drafted to design New Jersey’s second state prison in Trenton, which opened in 1836. Built on a radial plan, it also imposed the Pennsylvania system of solitary confinement. In Philadelphia, Moyamensing, the county facility at Eleventh and East Passyunk Avenue built to replace the Walnut Street Prison, also employed the Pennsylvania system of separate and solitary confinement—in its case, for individuals awaiting trial, along with those serving short sentences. Moyamensing remained the major hub for those facing and serving misdemeanor charges from its opening in 1835 until a second county facility, Holmesburg, opened in 1896. While Moyamensing remained open until 1963, Holmesburg, in northeast Philadelphia, remained open until 1995. Built as a solitary confinement prison, Holmesburg’s radial plan and castlelike stone walls mirrored Eastern State’s architectural aesthetic. Like Moyamensing, it held men and women who were awaiting trial or serving short sentences. As county facilities, Moyamensing’s and Holmesburg’s populations were more transient—though larger, in terms of sheer numbers—than the convicted felony population of Eastern State.

Abandoning Solitary Confinement

Eastern State did not officially abandon the philosophy of solitary confinement until 1913—more a veneer at that point—when prisoners were allowed to congregate for worship, sports, and other activities. Overcrowding forced the eventual construction of eight additional cellblocks, wedged between existing structures on the prison’s ten-acre plot of land. Outdated and expensive, Eastern State closed in 1970, and most prisoners were transferred to Graterford, in Montgomery County, which was built largely by prison labor and opened in the late 1920s as Eastern State’s “farm branch.”

In the mid-twentieth century, after American prisons moved to congregate models, Philadelphia became known for its diagnostic and classification services. In the 1950s, state prison systems became more professionalized, with formal guard trainings and new correctional entities; Pennsylvania established the Bureau of Corrections in 1953, and Delaware created the State Board of Corrections in 1956. Beginning in the early 1970s, the national prison population grew steadily due to a series of policy decisions: longer prison sentences and mandatory minimums, new laws and enforcement techniques, and increased reliance on prisons as a punishment for all crimes.

From 1790 to 1970, Philadelphia was home to a state prison and was known as the most important locality of penal pioneering in the country. The landscape of prisons changed drastically over the course of those centuries—and in the years that followed. Because of increased incarceration rates, the number of state prisons in Pennsylvania grew from seven in 1970 to twenty-four in 2017. By the early twenty-first century, the state was also home to dozens of additional local jails, federal prisons, and immigrant detention facilities. Many Pennsylvania prisons and jails operated over their capacity. To ease overcrowded conditions, advocates lobbied for a range of reforms: more lenient sentences, the end of cash bail, and modernized facilities.

By 2015, the era of mass incarceration had prompted a bipartisan coalition of legislators to push for sentencing reform and the reduction of the prison population. Yet in 2017 the United States continued to have the highest incarceration rate in the world—with 25 percent of the world’s prisoners but just 5 percent of the world’s population. Once a trailblazer in prison reform, a pioneer in both prison architecture and philosophy, by 2017 Philadelphia had the highest incarceration rate of any large jurisdiction in the country, with about 810 per 100,000 people in jail—making it one of the most incarcerated places in the world.

Annie Anderson is the manager of research and public programming at Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site and the coauthor, with John Binder, of Philadelphia Organized Crime in the 1920s and 1930s (Arcadia Publishing, 2014). She received her M.A. in American Studies from the University of Massachusetts Boston.

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Protesters target Pa. prison spending, expansion (WHYY, August 17, 2011)

- Philadelphia looks to build a new prison (WHYY, April 12, 2013)

- Camden county has jail overcrowding problem (WHYY, August 11, 2014)

- Schools work to avoid 'pipeline to prison' (WHYY, November 2, 2015)

- Technical violations fuel Philadelphia's jail overcrowding (WHYY, July 4, 2016)

- UPDATE: Guards taken hostage by inmates at Delaware prison (WHYY, February 1, 2017)

- Carney unveils prison improvement priorities (WHYY, March 13, 2017)

- Delaware leaders present concerns for prison inmates (WHYY, March 24, 2017)

- Delaware legislators search for answers about prison conditions (WHYY, May 16, 2017)

- Critics disappointed in preliminary Delaware prison report (WHYY, June 2, 2017)

- Racial disparities in Philly prisons persist despite 47% decline in incarcerated population (WHYY, March 23, 2023)

Links

- Arch Street Prison: A Prison Without Convicts (University of Leicester)

- New historical marker brings history of prison farm back to life (Delaware Public Media)

- Then And Now: 11th & East Passyunk Avenue (Hidden City Philadelphia)

- Incarceration Trend: Philadelphia County (Vera Institute of Justice)

- Philadelphia Challenge Site (Safety and Justice Challenge)