Quaker City (The); Or, the Monks of Monk Hall

Essay

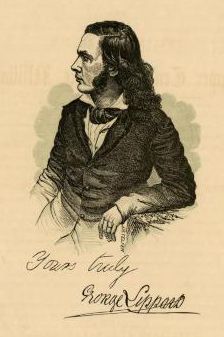

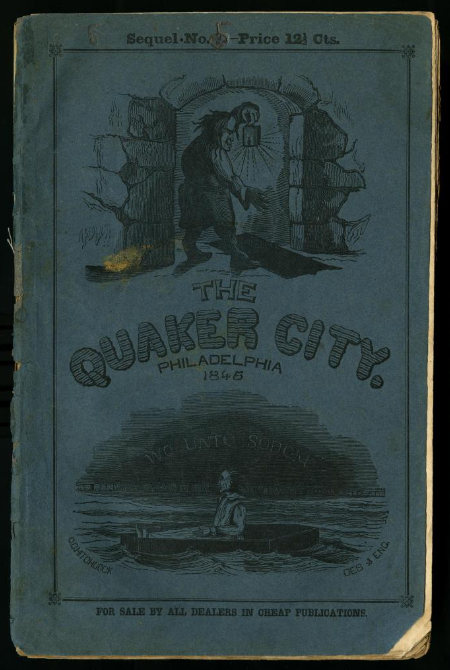

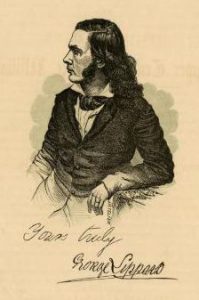

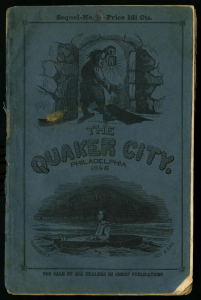

George Lippard (1822-54) published The Quaker City; Or, the Monks of Monk Hall in 1844-45 in serial installments, which were then collated as a novel. A gothic tale, set in Philadelphia and inspired by a linked pair of real-life urban crimes, the novel juxtaposes a plot centered on greed, amorality, and debauchery against the then-popular stereotype of an idealized Quaker of exemplary morals. As the “City of Brotherly Love” vision of Quaker William Penn (1644-1718) was widely known, Lippard counted on the irony that the novel’s characters and plot were neither brotherly nor loving.

In Lippard’s time, Philadelphia experienced a decade of rioting and destruction reflecting racial and class tensions, exacerbated by an ineffectual police force and a fractured urban region of more than two dozen municipalities within Philadelphia County. Lippard, who died when he was just 31 years old, made a successful decade-long career in journalism, playwriting, and historical fiction that promoted his commitment to social reform. Believing that society’s poor were overworked, underpaid, and powerless against exploitation by rich, powerful, immoral individuals and organizations, Lippard advocated a socialist system to improve their lot. Although Lippard was not himself Quaker, his frequent experiences with Quakers led him to identify them with his own politics. These experiences also informed his decision to present a Quaker character who is seemingly immune to the temptations of ordinary mortals.

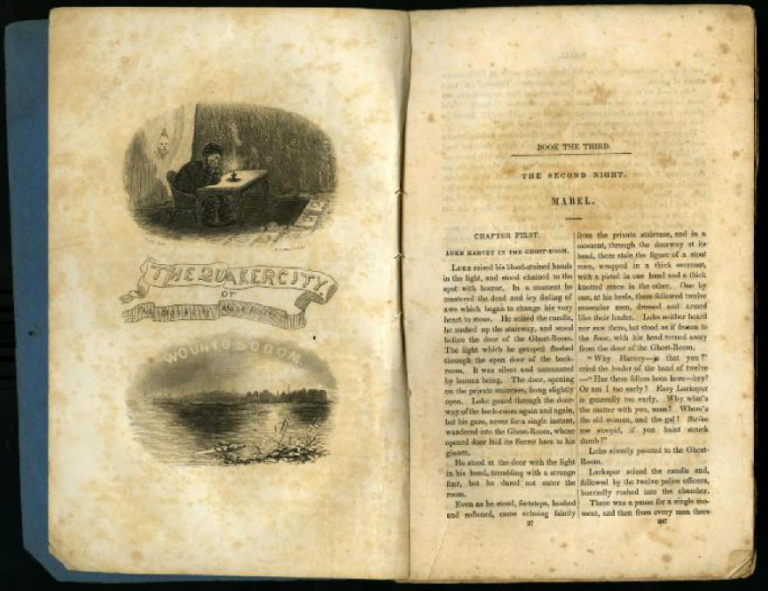

The Quaker City is built upon the highly publicized trial of a wealthy man who could afford an unethical lawyer to get him acquitted of murder. The novel’s lurid themes include a convoluted intertwining of plot lines, with multiple incidents of seduction, rape, drunkenness, and greed on the part of a club of privileged decadents—the Monks of Monk Hall—who flaunt their wealth and power. These plot lines are complicated by multiple murders: one man is prosecuted for killing in revenge for the rape of his sister, while another wealthier murderer is acquitted of poisoning his wife when he discovers that she is having an affair. Despite the title, Quaker characters are absent from the story until the final scene, when a nameless and ineffectual “Quaker” makes his appearance on a boat that is leaving Philadelphia, a scene that suggests that the moral influence of Quakerism was exiting what was once a “Quaker” city.

The term “Quaker” had been coined by detractors of the seventeenth-century Christian sect that labeled itself “the Religious Society of Friends.” “Quaker” was used to mock the sect’s impassioned—often trance-like—worship and social behaviors. By the mid-nineteenth century, when Lippard published The Quaker City, Quakers had acquired a reputation for behaviors that seemed to reflect a number of contradictory qualities: high-minded integrity as well as self-righteous rigidity; visionary nonconformity as well as antagonistic eccentricity; unwavering morality as well as wild-eyed fanaticism; nonviolence as well as emotional aloofness; and social-justice conviction as well as compassionless judgment. Lippard’s nameless Quaker character, making only a cameo appearance, seems to throw a spotlight on these tensions and ambiguities.

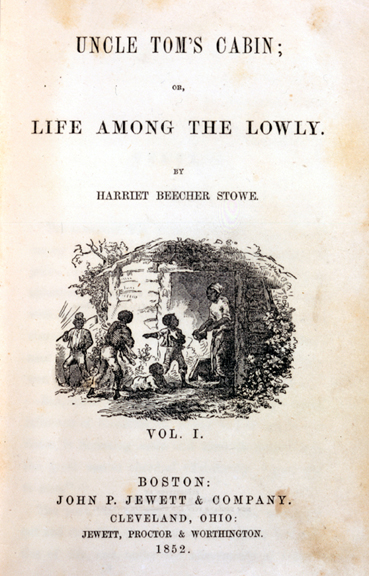

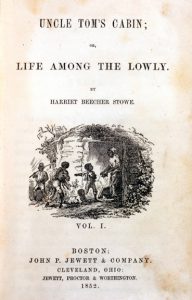

Until 1852, when Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811-96) published Uncle Tom’s Cabin—which also portrays Quaker characters as standard-bearers of morality—The Quaker City was America’s best-selling novel. With some 60,000 copies sold in its first year, the novel helped to solidify notions of urban life and capitalism as cauldrons of sin, greed, and debauchery, and to promote upstanding Quakers as the antithesis of urban low-life. In 1848, capitalizing on the novel’s popularity, and reflecting his admiration for Quaker ideals, Lippard began a newspaper called The Quaker City, which also promoted his progressive social justice ideology. Following the novel’s publication, at the nadir of Philadelphia’s administrative chaos, city and state officials took heed of the city’s lawlessness. In 1854, the disparate neighborhoods of Philadelphia city and county were consolidated under one unified police jurisdiction, a first for American cities.

Unlike Stowe’s novel, The Quaker City largely disappeared from popular consciousness. Still, Lippard’s portrayal of the romanticized “Quaker” remained an important part of a literary genre that left an indelible mark on American popular culture about what it means to be “Quaker” and the tension between urban realities and Quakers principles.

Emma J. Lapsansky Werner is Professor of History Emeritus at Haverford College, where she was Curator of the Quaker Collection. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History