Roman Catholic Church and Catholics

Essay

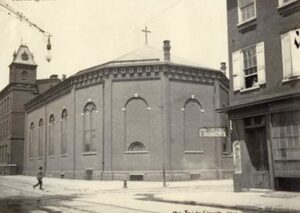

Philadelphia’s first Catholic Mass was heard in 1708. Despite English law prohibiting Catholic worship, broad religious tolerance had been laid out that year in the Pennsylvania Charter of Privileges by William Penn (1644-1718). The resulting legal tension came to a head in 1733 when a complaint about the “Romish chappell,” Saint Joseph’s in Willing’s Alley, prompted Pennsylvania’s Provincial Council to affirm that the colony’s religious freedom took precedence over the laws of England. Jesuit priests at Saint Joseph’s continued to hold Masses for forty or so English, Irish, and German parishioners. From this modest beginning, the Roman Catholic Church grew over the centuries to become the single largest denomination in the Philadelphia region, and Catholics became integral to civic life and the ongoing struggle for full religious freedom.

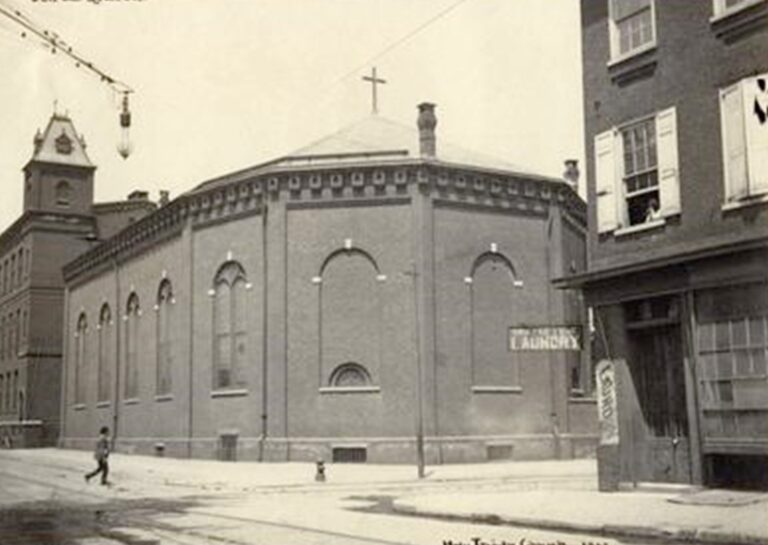

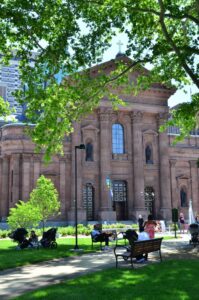

Philadelphia’s early toleration of Catholic worship enticed migrants from Europe and from other American colonies and increased Philadelphia’s Catholic population to fourteen hundred by 1757. To serve this growing community, a second Catholic church, St. Mary’s Church, opened on South Fourth Street in 1763. Catholic and Protestant leaders in Philadelphia congratulated themselves on their tolerant city, where a new and enlightened friendship promised to supplant the religious enmity of the Old World. During the American Revolution most of Philadelphia’s Catholics were patriots with no love for the English Crown, France’s and Ireland’s longtime foe, and a particular dislike for King George III. Their support won favor with the Continental Congress, whose members attended the first public religious commemoration of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1779, at St. Mary’s. Two years later, General George Washington (1732-99), an Anglican, heard a Solemn Mass of Thanksgiving at St. Mary’s for victory over the British. And on February 22, 1800, several Protestant members of Congress joined the Catholic community in a solemn Mass memorializing Washington after his death. This was remarkable because, at the time, a Catholic priest could face life imprisonment for saying Mass in England.

After the American Revolution, as the Catholic Church found its footing in the new republic, many Catholics hoped for a similarly democratic American Church. John Carroll (1735-1815), a Jesuit and the first Catholic Archbishop of the United States, argued that Catholics’ success in America hinged on their independence from Rome, writing that “the only connexion they ought to have with Rome is to acknowledge the pope as the Spiritual head of the Church.” Carroll’s convictions were shared by many of Philadelphia’s lay Catholics, who attempted to retain control of the churches they built and financially supported through a practice known as “lay trusteeism.” The Vatican, however, did not support a new church polity or expect the American church to be significantly divided from the global Catholic communion. This played out in a struggle that marked early Catholic life in the city and elsewhere, as laymen attempted to call and dismiss their pastors and factions broke out in support of competing clergy.

The fledgling Catholic community faced other challenges as well. The 1791 Haitian Revolution brought boatloads of Catholic refugees–both former enslavers and the formerly enslaved–to Philadelphia, while the 1793 yellow fever epidemic caused the deaths of roughly five thousand Philadelphians, around 10 percent of the city’s population. The church met the challenges of resettling refugees and of caring for the victims and orphans of the epidemic by rapidly deploying priests and religious women caregivers and developing an infrastructure of makeshift hospitals and settlements. This was especially crucial to the city’s survival when, in response to the fever, much of the city’s government and citizens with means fled. During their absence, Catholic and African American leaders stepped up to organize and maintain city functions. In the epidemic’s aftermath, Catholic steadfastness and service to the city were not forgotten.

Multicultural Challenges

In addition to these challenges, the multilinguistic and multicultural nature of American Catholicism also caused difficulties. German Catholics began lobbying for their own church where they could venerate German saints, play German music, catechize the next generation in German, and have pastors who spoke their language and understood their concerns. In 1784, approval was given for Holy Trinity Church to open as the first “national parish” in the U.S., built for German-speaking Catholics. This opened a tension, between maintaining a unifying geographic parish system and developing immigrant-supporting, ethnolinguistic churches, that continued in Philadelphia and other American cities.

In 1808 the Diocese of Philadelphia, encompassing Pennsylvania, Delaware, and South and West New Jersey, was created to support the nearly thirty thousand Catholics then residing in the region (until 1808 this area was part of the Diocese of Baltimore). After the young diocese’s first two bishops struggled to control lay trustees and the centrifugal force of a multinational Catholic populace, Pope Pius VIII appointed Irish-born Francis Kenrick (c. 1797-1863) as bishop, with a mandate to create stability and order. Kenrick inherited a range of other problems as well. Before and during his tenure, early optimism for Catholic and Protestant friendship was clouded by increasing anti-Catholic, anti-immigrant “nativism.” During the 1830s, Philadelphia endured repeated outbreaks of anti-Catholic violence, culminating in the rise of the American Republican Party (and its various “Know Nothing” cousins) and the 1844 Bible Riots (also known as Nativist Riots). The riots occurred over two different weeks in Philadelphia’s Catholic Kensington and Southwark neighborhoods. Together they resulted in the deaths of between twenty-five and forty people and the destruction of dozens of Catholic homes, a firehouse, two churches, and a convent. The riots were precipitated by Kenrick’s request that Catholic students be allowed to read the Catholic Douay version of the Bible rather than the Protestant King James version during the daily Bible reading mandated in Philadelphia’s public schools. His request was not honored, nor were any Protestant nativists held legally liable for the violence and destruction of the riots.

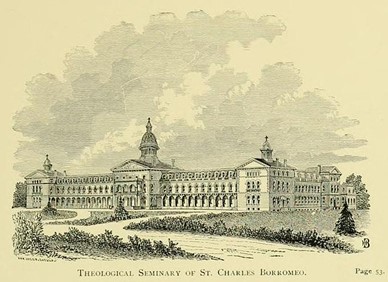

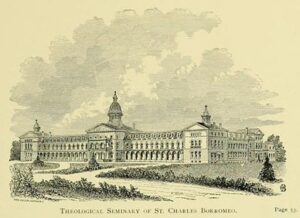

Kenrick also faced repeated cholera outbreaks among poorer Catholics in overcrowded neighborhoods and large waves of Catholic immigration due to the 1848-1849 German Revolutions and the 1845-1852 Irish Potato Famine. An able manager and institution builder, Kenrick secured the foundations to see the church through these troubles. He closed the prestigious St. Mary’s Church until its lay trustees handed over their keys and their power to call priests. He acquired all Catholic property on behalf of the institutional church. He established Philadelphia’s first diocesan newspaper, The Catholic Herald, and its first Catholic hospital, St. Joseph’s Hospital at North Sixteenth Street and West Girard Avenue under the direction of the Sisters of Charity. He founded the Catholic seminary, St. Charles Borromeo, and established Villanova College (Augustinian) and St. Joseph’s College (Jesuit). By the time he was created archbishop of Baltimore in 1851, the Philadelphia archdiocese had ninety-two Catholic churches and over 170,000 Catholics. At the same time, Kenrick also moved to give Catholics a firmer institutional and pastoral foundation in South Jersey, in 1848 appointing the first priest assigned primarily to the area, though Jesuit, Redemptorist, Augustinian, and diocesan clergy from Philadelphia continued to serve the sparsely settled region on missions there. In 1849 Kenrick blessed the first parish church in South Jersey, the Church of St. Mary in Gloucester.

The Parochial School System

After Kenrick’s tenure, Philadelphia-area Catholics continued to build the “cocoon” that would shelter them from nativism and create solidarity among immigrants of varied backgrounds. Key to their success was the development of the parochial school system and the proliferation of popular religious devotionalism that brought them together as a community and brought the pride of the community out onto the streets. Saints’ parades, May devotions honoring Mary, and first Holy Communion processions of children in white suits and dresses showed the devout side of Catholic life. The raucous mummers (belsnickles) hailing from the Irish and Italian Catholic neighborhoods of South Philadelphia displayed their rowdier creativity and culture in sporadic, impromptu performances later supplanted by an established parade route.

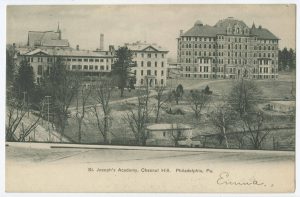

In this mid-to-late-nineteenth-century period of growth and expansion, Bohemian-born Bishop John Nepomucene Neumann (1811-60) brought to the diocese his deep spirituality, formed among the Redemptorists (the Congregation of the Most Holy Redeemer community of priests and brothers). Mastering six languages to speak to his multilingual flock in their native tongues, and visiting every parish in the archdiocese each year, Neumann offered a more pastoral style of leadership. But, like his predecessor, he built the institutions needed to steer the church forward. Neumann established over two hundred parochial schools and built new churches at the rate of almost one per month. He supported new immigrant communities by creating the Beneficial Bank to protect their savings and, in 1852, established an Italian-language national parish, St. Mary Magdalene de Pazzi at 712 Montrose Street. During this time of church growth, Neumann also requested that New Jersey be formed into a separate diocese, and in 1853 the church created the Diocese of Newark which encompassed all of New Jersey. Neumann was canonized in 1977, becoming the first American male saint. His shrine was established at St. Peter the Apostle Church at 1019 N. Fifth Street, Philadelphia.

During these years, the African American Catholic community grew as well. Black Catholics were the descendants of Haitian and other Afro-Caribbean immigrants, transplants from New Orleans and other Southern cities, and converts who encountered Catholicism through Philadelphia’s churches. They were initially segregated into separate “Negro Masses.” Over time, four Black Catholic parishes were established in Philadelphia: St. Peter Claver (1886), St. Ignatius of Loyola (1893), St. Catherine of Sienna (1922, exp. 1956), Our Lady of the Blessed Sacrament (built 1887, est. 2005). In 1892, The Journal newspaper was founded to serve Philadelphia’s growing African American Catholic community. African American men who, due to white racism, were denied admission into the Catholic Knights of Columbus fraternity, founded the Knights of Peter Claver Catholic brotherhood for fellowship and mutual support. The Oblate Sisters of Providence, a Baltimore-based Black congregation of women religious, served African American children in Philadelphia. Black Catholics also found a patroness in Katharine Drexel (1858-1955), the Philadelphia heiress who donated her large fortune to the church and founded the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament in 1891 to serve underprivileged Native American and African American communities. While aspects of Drexel’s legacy have been contested due to Native American cultural erasure, she and the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament provided education for African Americans in Philadelphia and throughout the U.S, founding the only historically Black Catholic College, Xavier University in New Orleans, Louisiana. In 2000 Drexel became the second Philadelphian to be canonized.

The twentieth century saw the emergence of Philadelphia Catholics from their “cocoon.” While the parochial school system continued to flourish and expand, Catholics were also well represented in the public schools, the police force, political offices, and all aspects of Philadelphia’s professional and cultural life. Dennis Joseph Dougherty (1865-1951) led the church into this period of cultural dominance. Installed as archbishop in 1918, and created cardinal in 1921, his decisive and confident leadership inspired Catholics to boldly proclaim their faith. Known as “God’s bricklayer,” Dougherty aggressively expanded the church’s presence across the Philadelphia area, establishing 112 parishes, 145 parochial schools, 53 high schools, twelve hospitals, and other institutions and encouraged Catholics homeownership as a foundation for parishes with Catholic savings-and-loan banks providing needed capital. He also drew upon the economic power of the city’s Catholics to enact a boycott against movie theaters until the film industry stopped depicting immoral content. This flexing of power closed dozens of theaters and showed other Philadelphians that the Catholic community was willing to shape their city through more than just church and school building.

Catholic Increases in the Suburbs

Rapidly changing demographics in Philadelphia in the early to middle twentieth century challenged urban parishes and led to increasing Catholic populations in the suburbs. As Philadelphia’s African American population increased with the Great Migration from the South, real estate interests, lenders, and the federal government “redlined” Black neighborhoods and severely limited them from getting government subsidized mortgages and home improvement loans. Residents of these neighborhood also experienced absentee landlords, inadequate city services, and aggressive policing. Many white Catholics who resided in these neighborhoods and other areas of the city joined in the white flight to the Philadelphia and South Jersey suburbs, moves encouraged and facilitated by the church’s rapid establishment of new parishes there, which assured Catholics of a parish church, school, and Catholic community. City parishes began to include many more Black Catholics, whose presence shaped these communities in new ways. They also began to seek converts among and offer charitable relief to their new African American neighbors. Some parishes continued to segregate Black Catholics or treat them as second-class members. Others, such as St. Malachy’s on North Eleventh Street, committed themselves to the work of racial integration, community service, and civil rights. In cities such as Philadelphia, Camden, and Chester, the parochial school system increasingly served the most vulnerable and marginalized children, offering high quality, generally affordable private religious education to Catholic and non-Catholic children alike. At the same time, better endowed parochial and private Catholic schools grew in the suburbs across the region, adding to the appeal of such places for white Catholics wishing to escape changing cities.

Catholic parishes in Philadelphia-adjacent suburbs grew rapidly during this period, establishing new churches and parochial schools. As Catholics moved to the suburbs, old ethnic divisions between English, German, Italian, Irish, and other European Catholics began to lose their salience and were subsumed under the racialized label “white.” In most suburbs, Catholics were a minority and banded together to create thriving communities of support. While some ethnocultural differences persisted, especially in inner-ring suburbs such as Upper Darby and Lansdowne, in Delaware County, to name two, many Catholics sought and gained social acceptance through the process of suburbanization and ethnic homogenization.

Twenty-First Century Challenges

In the twenty-first century, the Catholic population had grown such that the original area of Philadelphia Archdiocese was served by eleven separate dioceses, while it served five Pennsylvania counties: Philadelphia, Bucks, Chester, Delaware, and Montgomery. However, like Christianity more broadly, American Catholicism began losing members in these decades. In the Northeast, the Catholic share of the population decreased nine points from 36 percent to 27 percent between 2009 and 2019. The Church also faced challenges related to the priest sex-abuse scandal, which was widely covered by the media. While the majority of American Catholics surveyed in 2019 said that the Vatican was handling the scandal well and that the problems were not unique to their church, financial settlements in abuse cases cost the Philadelphia Archdiocese and the Camden Diocese millions of dollars, and claims against other dioceses in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware remained unsettled in 2021. This, coupled with a declining population and aging buildings, stressed Philadelphia’s Catholic infrastructure. Parishes closed, cemeteries were leased to private companies, and parochial schools merged or shifted to the control of a nonprofit, Independence Mission Schools. At the same time, a rapidly declining number of priests, and an aging clerical population generally, created staffing problems for churches across the region.

Still, Philadelphia continued to support a thriving Catholic community. While 85 percent of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia’s Catholics were non-Hispanic whites in 2015, the Church welcomed new waves of immigrants from Asia, Southeast Asia, the Caribbean, Mexico, and Latin America, and a growing Puerto Rican community. In 2018 the archdiocese counted roughly twenty-two thousand registered Spanish-speaking Catholics. Drawn from across Puerto Rico, Mexico, the Caribbean, Central America, and South America, they brought many popular religious traditions and expressions to the archdiocese, which the church tried to respect by allowing festivals and recognition of particular religious icons from each group while also supporting an annual archdiocesan celebration of Our Lady of Guadalupe as an appeal to a common “Hispanic” identity. In southern New Jersey, Latinx migrants and workers added to the ethnic mix of the larger Catholic population. Ministries such as the Catholic Social Services of the Archdiocese of Philadelphia and the Aquinas Center gave practical and legal support to immigrants, refugees, and migrants. In response to these later demographic shifts, the archdiocese moved away from the national parish model to support multilingual, multiethnic “shared” parishes with distinct but overlapping congregations attending services in different languages in one church.

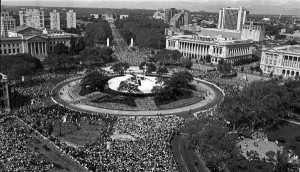

In September 2015, Philadelphia hosted the triennial World Meeting of Families that brought over twenty-thousand attendees from all over the world. During the event, Pope Francis concluded his six-day United States visit with a two-day pastoral visit to Philadelphia and an open-air Mass attended by over one million people. He addressed many pressing issues including the priest sex-abuse scandal and the importance of the family, and met with school children, seminarians, and incarcerated people. The meeting and papal visit acknowledged and celebrated the vital role that Catholics have played and continue to play in the Philadelphia region.

Bishop Nelson J. Perez

In 2017, Bishop Nelson J. Perez became the first archbishop of the diocese with Hispanic heritage. He had previously served as episcopal vicar for Hispanic ministry and serves on the Bishop’s Standing Committee on Cultural Diversity and the Pontifical Commission for Latin America. During the Covid-19 pandemic, which began shortly after Bishop Perez’s installation in February 2020, he suspended all public masses but moved rapidly to continue to support Catholic community, worship, support, and outreach in the city, declaring, “the Catholic Church in Philadelphia is not closing down. It is not disappearing, and it will not abandon you.”

Despite many changes and challenges, Catholics continue to shape life in Philadelphia and the Delaware Bay region. According to U.S. Census data and pastoral reports, in 2010 29 percent of the population of the archdiocese were registered Catholics, with many more non-registered Catholics. As of 2018, there were 125 parishes, 800 diocesan priests, 2,522 men and women religious, 10 Catholic colleges and universities serving over 35,000 students, and 141 diocesan, parochial, and private Catholic schools serving over 47,000 students. By 2020 the Diocese of Camden, which the church erected in 1937, consisted of sixty-two parishes covering the counties of Atlantic, Camden, Cape May, Cumberland, Gloucester, and Salem, and counted roughly 486,000 Catholics. Philadelphia is indebted to its Catholic citizens who have contributed to all aspects of the city’s life and continue to provide resources, cultural, and religious contributions to the diverse life of the city.

Elizabeth Hayes Alvarez is Associate Professor of Instruction at Temple University’s Religion Department. She received her Ph.D. in the History of Christianity from the University of Chicago. Her book, The Valiant Woman: The Virgin Mary in Nineteenth-Century American Culture (University of North Carolina Press, 2016), explores Marian imagery and the female ideal in American popular culture. She also published an edited collection, Religion in Philadelphia.

Copyright 2022, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- History May Lie Deeper Under A Church Rectory In South Philly

- Set Apart: Religious Communities in Pennsylvania

- Church Listed on the National Register Razed for New Construction

- The Catholic Herald (Villanova University Falvey Library)

- Archdiocese of Philadelphia

- Diocese of Camden

- Diocese of Wilmington