Salem (City), New Jersey

Essay

As the earliest English Quaker settlement along the Delaware River, the city of Salem was a key port at the mouth of the Salem River in the seventeenth century. Established in 1675 prior to both Philadelphia and Burlington, it was quickly overshadowed by Philadelphia. However, its proximity to the Philadelphia market by ship, steamboat, and railroad spurred additional industry during the nineteenth century, particularly glassworks, flooring manufacturing, and canneries. The closure of former manufactories in the late twentieth century created a pressing need for jobs and industry, as the city declined through population loss, unemployment, and poverty. Government programs and private organizations endeavored to renovate vacant buildings, decrease crime, and revitalize the Salem waterfront, with hopes of bringing new industries to the Port of Salem.

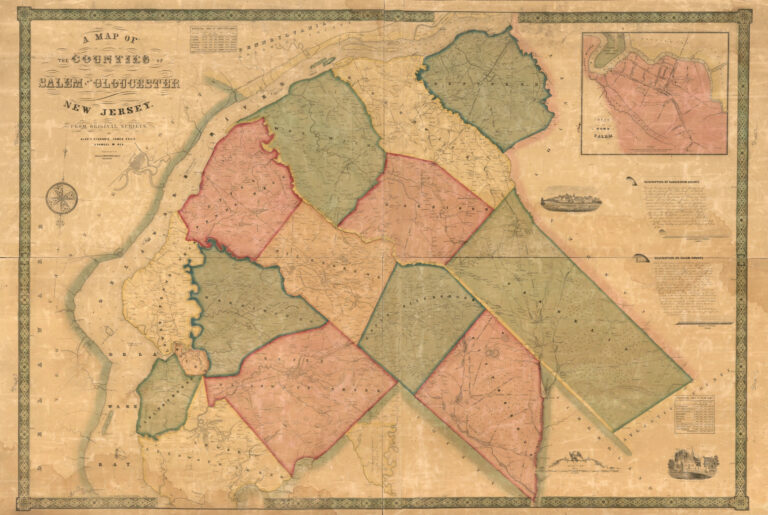

The city of Salem is located three miles from the mouth of the Salem River, which was called “Asamhocking” by the original Lenape people. As various groups of European settlers arrived in the seventeenth century, the Dutch renamed the river “Varkens Kill” (Hog Creek). After English settlers from New Haven briefly attempted to establish a colony there in 1641, the Swedes built Fort Elfsborg at the mouth of the river to assert their authority. Swedes continued to vie with the Dutch for control of the region until it came under English rule in 1664. Colonist John Fenwick (1618-83) arrived with Quakers and other Englishmen in 1675; he christened the river the “Salem River,” with its southeastern tributary named “Fenwick’s Creek.” According to English law, Fenwick owned a one-tenth proprietorship of West Jersey, comprising the later Salem and Cumberland Counties, and he affirmed his claim by purchasing the land from the resident Lenape.

In 1676 Fenwick founded the town of Salem, the name signifying peace, and established the first two streets—Wharf Street (later named Broadway) and Bridge Street (later Market Street). By 1682, Salem served as a port of entry, and the town hosted weekly markets and annual fairs. Early settlers exported grains (wheat, corn, rye, and oats), animal products (beef, pork, tallow, and pelts), and timber (cedar posts, shingles, staves, and cordwood) to New York, Boston, and the West Indies. As their wealth increased, some Salem residents purchased enslaved persons from the West Indies and Africa to conduct housework and farm labor, alongside indentured servants and a handful of enslaved Native Americans.

When Salem County officially organized in 1694, Salem became the county seat, and it incorporated as a town in 1695. To connect Salem with Burlington, at the time the other principal town of West Jersey, the West Jersey Assembly commissioned the Kings Highway in 1681. Other major roads connected Salem with Greenwich to the south. Travelers followed these stage routes to reach the ferry from Salem to New Castle, Delaware, and the ferries from Gloucester and Cooper’s Ferry to Philadelphia.

An Era of Civil Unrest

As New Jersey transitioned from royal colony to American independence, Salem became the setting for civil unrest. The colonial customs collector at Salem Port was universally disliked, tainting public opinion of the British government. Sympathetic to the patriot cause, many citizens of Salem contributed monetary aid for the besieged citizens of Boston in 1774, yet pacifist Quakers strongly opposed the American Revolution. With the outbreak of war, British troops briefly occupied Salem in March 1778 while foraging supplies and terrorizing the rural population. The following November and December, the Revolutionary government tried for treason their Loyalist neighbors who had aided the British, as the conflict led to lingering resentments.

Salem grew considerably during its first century as its population reached 929 in 1810. Most of the initial settlers were Quakers, who obtained land in 1681 for their first meetinghouse and a cemetery on Broadway. A large influx of English settlers and descendants of the Swedish settlers formed an Episcopal church in 1722, followed by Baptist, Methodist, and Presbyterian churches. As the largest town in the county, Salem contained a bank, several newspapers, a library, and the Salem Academy. Tradesmen and merchants flocked to the city’s streets.

The Quaker influence significantly reduced slavery in Salem County during the years after the American Revolution. More than eighty citizens from the Salem area, both Quaker and non-Quaker, signed an anti-slavery petition in 1770. By the following decade, Salem Quakers had eradicated slavery within their ranks, and many other slaveholders had followed suit. In 1797, Salem included about seventy-five Black residents, of which about thirty-five were free, fifteen were enslaved, and twenty-five were bound out serving a set number of years before freedom. The emerging free Black population soon developed a distinct community. The children attended schools taught by Black teachers, Quakers, or other educators. Rev. Reuben Cuff (1764-1845) established Salem’s first Black church by 1800, forerunner of both Mt. Pisgah African Methodist Episcopal Church and Mt. Hope United Methodist Church.

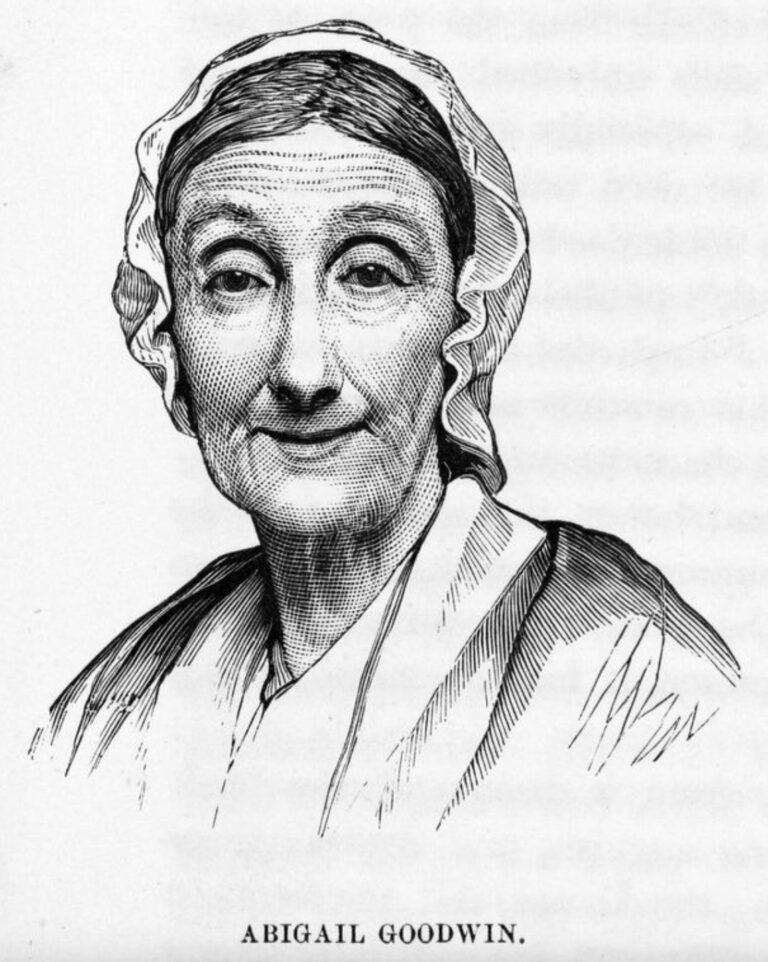

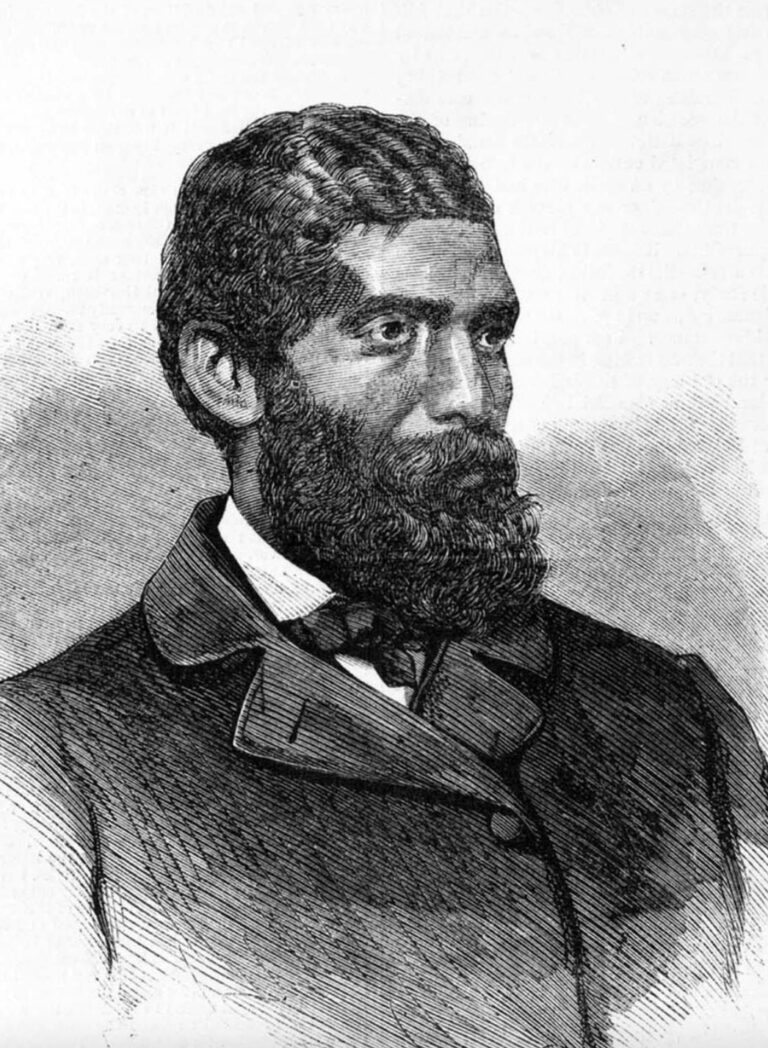

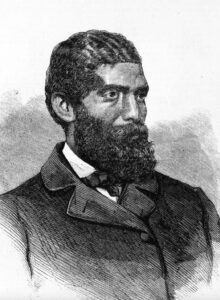

By 1830, over one thousand free Black residents lived in the Salem area, with only one person still enslaved in the county. Many were new arrivals, formerly enslaved in Delaware, Maryland, or Virginia, who had followed the Underground Railroad and crossed the Delaware River to Salem and freedom. The citizens of Salem responded to this influx with contrasting actions. A few returned the fugitives, but a large crowd of Salem residents spontaneously came to the rescue when a slave catcher attempted to abduct several Black residents one night in 1834. Prestigious abolitionists of Salem included Quaker Abigail Goodwin (1793-1867), whose home operated as a safe house; self-emancipated Amy “Hetty” Reckless (1776-1881), who was active in the Philadelphia Female Anti-Slavery Society; and Dr. John S. Rock (1825-66), who studied dentistry in Salem before practicing law in Boston, leading to him being the first African American admitted to practice before the United States Supreme Court.

River Traffic Grows

Enslaved freedom seekers took advantage of the increased river traffic between Delaware and Salem, as Salem was located only five miles from the mouth of the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal. Although the Salem Port no longer handled international trade after the American Revolution, steamboats ran regularly from Salem to Delaware and Philadelphia by the 1830s, transporting both people and goods. As the need for shipping increased, shipbuilders in Salem responded by producing schooners, canal boats, brigs, and steamboats.

From 1840 to 1850, Salem’s population jumped over 50 percent, from 2,006 to 3,052 residents. After a surge of working-class immigration from Ireland and Germany, St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church opened in 1852 to serve the town’s Catholic residents. Around two hundred Black residents lived within the town limits, but substantial Black populations also lived in Claysville directly across the covered bridge over Fenwick Creek, as well as in other nearby Black communities in Mannington and Elsinboro. Several were employed by Salem households and businesses, as well as attending church and school within the town. While Salem offered new opportunities for freedom, it did not yet offer full equality. This was poignantly demonstrated when the New Jersey Legislature rejected a petition for equal suffrage signed by John Rock among other petitions introduced in the state’s first Colored Convention in 1849.

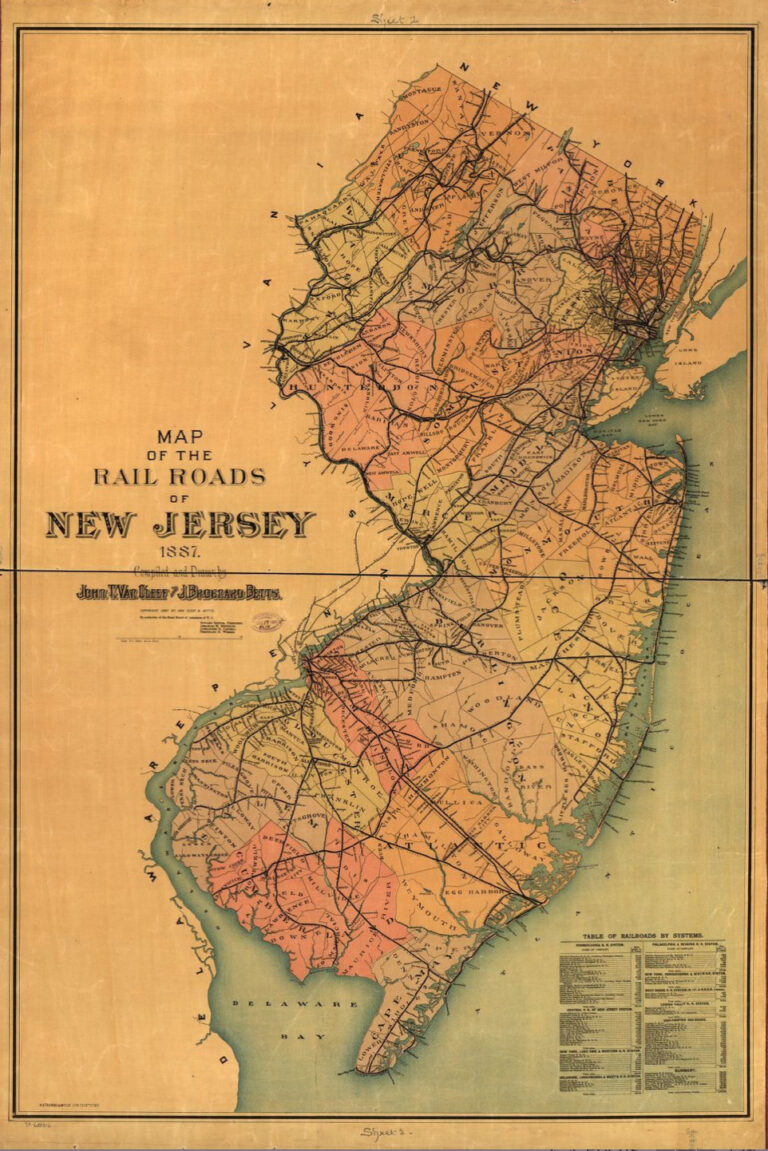

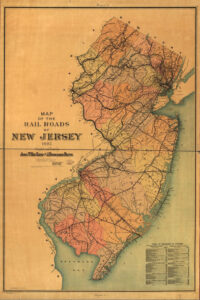

Salem incorporated as a city in 1858. At the onset of the Civil War a few years later, the city immediately mustered volunteers, both Quaker and non-Quaker, for the Union Army. In 1863, the Salem Railroad—constructed between Claysville, just over Fenwick Creek from Salem, and the West Jersey Railroad in Elmer—linked the city of Salem to markets in Camden, Philadelphia, and New York. This changed the primary means of travel from steamboats to rail. In 1882, the railroad extended to Salem City over a new bridge across Fenwick Creek, and the Woodstown-Swedesboro Railroad opened the following year, linking Salem more directly to northern cities.

Rail service spurred industry. The Salem Glass Works was established in 1863, and Gayner Glass also operated in Salem beginning in 1879. Another prominent industry was flooring manufacturing, beginning with the American Oil Cloth Company in 1868 and culminating with Mannington Mills, which started as Campbell Manufacturing in Salem but relocated to Mannington Township in 1924 and remained a significant flooring manufacturer into the twenty-first century. Capitalizing on the primarily agricultural county, Salem hosted a variety of fruit and vegetable canneries, including the H. J. Heinz food processing plant that operated from 1906 to 1977. The Ayars Machine Company, established in 1878, produced machines for canning, which had an international market. These and other factories provided both goods for export and employment for residents.

Industrial Growth of World War I

With the outbreak of World War I, industry boomed at the DuPont Powder Works and Chamber Works in the Penns Neck region north of Salem, and workers poured into the area seeking employment. DuPont remained a major employer for the rest of the century. A trolley line opened from Salem to Penns Grove in 1917 to provide easy transportation for DuPont employees, operating until 1933. Drawn to the job opportunities, European immigrants and southern Blacks added to the diversity of Salem’s population. A small immigrant Jewish population formed the Congregation Oheb Shalom in 1903.

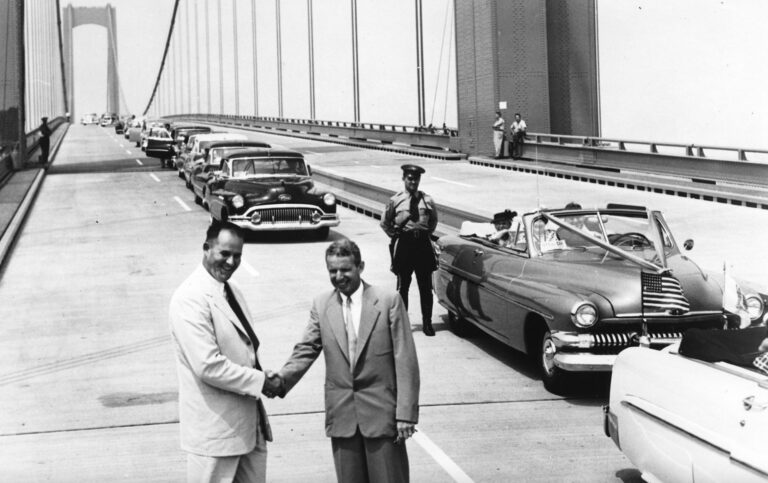

As automobile usage increased, railroad usage waned. By 1928 the number of passenger trains arriving in Salem daily had fallen from eight to two, and passenger service ended completely in 1950. Instead, buses provided public transportation to Camden and Philadelphia. Responding to the demand for automobiles, several car dealerships located in Salem, although they moved out of the city for more room to expand after World War II. The construction of the Delaware Memorial Bridge in 1951 permanently shifted transportation from river and rail to roads and highways.

For most of its history, Salem’s population rose steadily until peaking at 9,050 in 1950. Since then, the population fell as poverty increased. In the latter half of the twentieth century, factories and small businesses closed, prompting a rise in unemployment, poverty, rentals, and deteriorating housing. Because Salem had a large Black population, racial tensions aggravated the situation. State law mandated school integration in 1947, but several Salem restaurants and places of entertainment continued to be segregated. An NBC television special in 1964, which calculated that Salem most embodied “Average Town USA,” also revealed white racist attitudes. Racial tensions escalated in 1966-1967 with a brief rash of cross burnings, which were halted after a peaceful NAACP march in Salem and a petition signed by both Black and white members of the community. At the time, African Americans comprised 29 percent of Salem’s population, but during the following decades, they eventually became the majority. By 2010, Salem was 62 percent Black, with 7 percent Hispanic. Salem elected its first Black mayor in 1992, and both the city council and the police force became increasingly reflective of the city’s overall demographics.

Meanwhile, Salem was experiencing an economic downturn. Both the Heinz Plant and the Gayner Glass factory closed in 1977, and the sewing factories closed in the 1980s. Eventually, Anchor Hocking Glass remained the only major employer in Salem. To continue freight service to the glass factory, the Salem County government purchased the rail line from Swedesboro to Salem in 1985. In 2011, Anchor Glass Container Corporation still maintained 350 employees, but Salem’s glass factory closed permanently in 2014, leaving many of the city’s workers suddenly unemployed. Although the jail relocated to Mannington in 1994, Salem’s county offices expanded within the city, employing both city and county residents. City residents also commuted to major employers in neighboring townships such as Mannington Mills, Salem Medical Center, PSEG’s Salem Nuclear Generating Station, and Chemours at the former DuPont Chamber Works site.

Port of Salem Reestablished

Reestablished in 1982, the Port of Salem brought international trade back to the area through companies such as Mid-Atlantic Shipping and Stevedoring and Sandpiper International Steamship Agencies, which handled weekly exports to Bermuda. The South Jersey Port Corporation acquired the municipal wharf in 1994, operating it as the Salem Marine Terminal. In 2018, the city council adopted the Salem Waterfront Redevelopment Plan, seeking to capitalize on the Port of Salem and highlight its status as a Port of Entry, a Foreign Trade Zone, Urban Enterprise Zone, and Opportunity Zone. The county government began restoring the railroad, hoping to attract new industries to Salem by offering rail service connecting with the port.

To assist with Salem’s revitalization several organizations sought to preserve historic buildings, such as the Market Street Improvement Association in 1975 and Preservation Salem Inc. in 1990. Founded in 1988, Stand Up For Salem was designated as a Main Street Program in 1999 and initiated several programs that contributed both socially and economically to the renewal of Salem, including a Community Development Neighborhood Plan in 2011.

Poverty was a serious obstacle in Salem, as unemployment reached 18 percent in 2010 and over 20 percent of the households received public assistance. Most Salem residences were rentals, with several hundred vacant homes, despite the demolition of over a hundred buildings during a five-year period. The closure of the city’s only grocery store in 2017 threatened to turn the city into a food desert. By 2020, the poverty rate had reached 42 percent, and the population had dropped to about 4,700, almost half of what it had been in 1950. Because of its substantial low-income population, the Salem City School District was designated in 2004 as one of New Jersey’s Abbott districts [cm1] (later referred to as SDA Districts), receiving state funding to ensure Salem could offer adequate public education. With about a quarter of the residences vacant in Salem, the Neighborhood Transformation Initiative provided mortgages from the USDA to low-income households to encourage home ownership. The city also sought to combat violence, drugs, and unemployment with a variety of initiatives.

Despite multiple setbacks, the city of Salem maintained its charm with renovated colonial homes in the historic districts along Market Street and Broadway, attracting visitors from the Greater Philadelphia area with events such as the annual Magic of Christmas Parade, the Yuletide Tour of Homes, and the Walking Ghost Tour. Although employment opportunities had diminished in the city, residents still commuted by bus or car to jobs in South Jersey, Philadelphia, and Delaware. Dedicated city and state officials and citizens continued to work to revitalize the city, with hopes of seeing an influx of new industries and the Port of Salem bustling once again.

Bonny Beth Elwell is a Salem County historian and genealogist, serving on the board of several historical organizations. She works as the editor of the Elmer Times newspaper, the Library Director of the Camden County Historical Society, and is the author of Upper Pittsgrove, Elmer, and Pittsgrove (2013) and other publications. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2022, Rutgers University.