Spanish-American War

Essay

Although often regarded as a minor conflict, the Spanish-American War (1898) made a major impact on Greater Philadelphia. As a populous urban center, Philadelphia and its immediate environs contributed a substantial number of troops to the United States’ volunteer army but also provided an outlet for those dissenters who decried warfare. In addition, the war influenced the region’s economy by significantly boosting war-production manufacturing while also creating shortages that affected local industries and consumers. After the successful conclusion of hostilities, Philadelphia hosted a three-day victory festival that drew national attention, but debate continued over the United States’ acquisition of former Spanish territory. And over half a century later, one of the Spanish-American War’s most celebrated warships became a floating museum docked at Penn’s Landing.

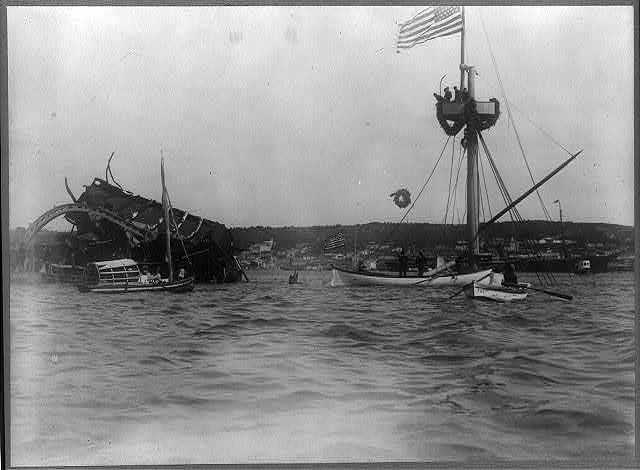

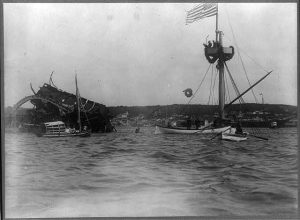

The Spanish-American War propelled the victorious United States into the forefront of world affairs, allowed America to take a seat among leading military powers, and established the young nation as a fledgling empire. A unique combination of social, economic, and political pressures helped push the United States into open warfare against Spain, but officially, President William McKinley (1843-1901) asked Congress for the authority to commit American troops in order to liberate Cuba, and its people, from oppressive Spanish rule. Once war had been declared on April 25, 1898, the U.S. government began recruiting state National Guard regiments to create the foundation of a national army. Aroused by months of inflammatory newspaper articles that vividly depicted Spanish atrocities and Cuban suffering, and stimulated to patriotic heights by the sinking of the USS Maine in Havana harbor, Philadelphia-area residents did not hesitate to enlist. Philadelphia contributed four regiments of volunteer infantry (the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 6th), one battery of artillery (Light Battery A), and one troop of cavalry (First Troop Philadelphia City Cavalry) for a total of 4,849 soldiers. Wilmington and northern Delaware sent almost three hundred men (Companies A, C, F, H, and K) into the Army. In New Jersey, Camden County opened a recruiting office to fill a proposed Sixth Regiment, but the war ended before the Sixth could be mustered into service. Of all these volunteers only Light Battery A and the First Troop City Cavalry deployed for service overseas, although an armistice was declared before they saw action. Sailors from the area, however, served aboard warships that engaged in combat in both Cuba and the Philippines.

Although local support for the war was pervasive, it was not unanimous. The Universal Peace Union, based in Philadelphia and led by Alfred H. Love (1830-1913), condemned armed conflict with Spain before and after hostilities began. Love went so far as to send a peace initiative to the Spanish Queen Regent, by a European courier, after the United States declared war. When this came to light, the Philadelphia Bulletin openly questioned his loyalty, inciting angry mobs to march on his home and burn his bullet-ridden effigy in Chester. Denounced as a traitor, he was even turned away by the prisoners of Eastern State Penitentiary, where he had counseled inmates every Sunday for the previous forty-two years. Meanwhile, the City Council, under political pressure, evicted the UPU from its office on Independence Square.

Munitions Surge

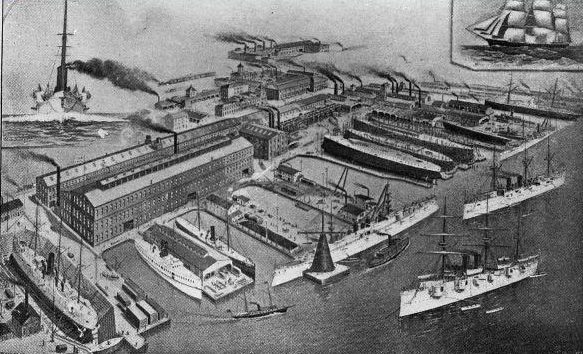

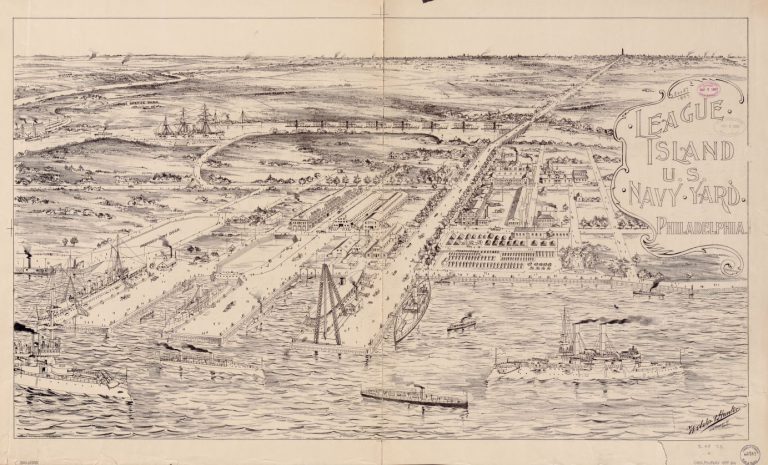

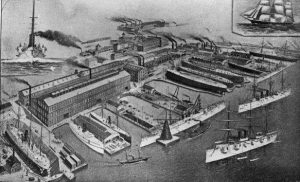

The war economy bestowed benefits but also imposed hardships. On the upside, military manufacturing provided employment for men, women, and even children still suffering from the Panic of 1893. E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company, attempting to supply the government’s insatiable need for gunpowder, aggressively expanded operations and hiring at its brown powder mill north of Wilmington and its smokeless powder plant in South Jersey. Camden shipbuilder John H. Dialogue and Son employed workers to build U.S. naval vessels. In Philadelphia extensive shipyards such as William Cramp & Sons and League Island Navy Yard, in addition to building large warships, added extra shifts to provide gunboats to patrol and protect coastal waterways. Workers at Midvale Steel and the Frankford Arsenal worked around the clock to produce naval artillery and small arms ammunition, while smaller companies and seamstresses working at home labored to provide American fighting men with apparel and accoutrements. Everything from uniforms and tents to buttons, blankets, caps, and summer drawers were stored or produced in the Schuylkill Arsenal.

While the war with Spain benefited some industries, the conflict in Cuba threatened to disrupt others. During the early months of 1898, as tensions increased between the United States and Spain, local cigar manufacturers, anticipating hostilities, imported as much tobacco from Cuba as they could, even purchasing supplies previously shipped to Europe. By the time war began, farsighted Philadelphia-area cigar makers had stockpiled enough Cuban tobacco to keep their workers rolling and their customers smoking for at least another year. Philadelphia sugar manufacturers faced a different dilemma. An ongoing two-year struggle between revolutionaries and Spanish authorities had already impeded Cuban sugar exports and forced desperate refinery owners to search the world for other sources of supply. When war between the United States and Spain began, raw sugar from such distant places as Java, the Philippines, Egypt, and Mauritius in the Indian Ocean made its way into Philadelphia ports. During the war, thousands of tons of beet sugar from Germany were also imported. These alternative sources of sugar enabled refineries in Philadelphia to continue operating.

These auxiliary supply strategies kept the cigar and sugar industries running but increased costs for consumers. Throughout the Philadelphia region, shortages caused by the war resulted in higher prices for food staples such as oatmeal, beans, meat, canned fruits and vegetables, potatoes, coffee, and tea. Flour became exceptionally dear and the price of bread skyrocketed. Prices rose so rapidly that distributors of flour became reluctant to sell large quantities because they expected that they might make a greater profit at a later date. Prices also increased and availability dropped for dry goods such as duck and dyed cotton, which were in great demand for Army use.

After suffering two crushing naval losses and with its armies on the brink of defeat, Spain accepted the futility of continuing the struggle and negotiated an armistice that began on August 12, 1898; a formal peace treaty followed four months later. Once hostilities concluded, the city of Philadelphia planned a Peace Jubilee to celebrate the nation’s victory over Spain. The focal point of the Philadelphia Peace Jubilee was the construction of a towering, electrically illuminated, Athenian arch that spanned Broad Street near Sansom, bisecting a Court of Honor of ornate columns lining Broad Street from City Hall to Walnut Street. The celebration commenced on October 25, 1898, with a grand naval pageant of boats on the Delaware River. Two days later twenty-five thousand soldiers, many from Philadelphia, marched down the Court of Honor under the respectful gaze of President William McKinley. The festivities concluded October 28 with a vast civic parade representing many of the city’s diverse ethnic, social, business, civil, and educational organizations. Spectators traveled from all over the United States to attend, and most major newspapers covered the occasion.

Questioning Imperialism

As in the rest of the United States, the aftermath of the Spanish-American War led some Philadelphia-area inhabitants to openly question their nation’s new role as an imperial power. After the war, American soldiers remained overseas to occupy Cuba and America’s new possessions: Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippine Islands. Generally, these occupations were temporary and peaceful, but in the Philippines U.S. troops combatted a fierce native insurgency for years. Staunch Filipino resistance compelled the Philadelphia American League (1899) to condemn imperialism as a violation of the republican principle of government by consent of the governed. Philadelphia African Americans also spoke out against American colonialism. Black newspapers such as the Philadelphia Defender, Odd Fellows Journal, and the Christian Banner sympathized with the plight of the Filipinos but remonstrated that the United States government should worry less about foreign entanglements and, instead, redress the lack of equality and civil rights endured at home by its own citizens of color.

The region later gained a visible monument to the Spanish-American War in the form of the USS Olympia, the flagship of the U.S. Asiatic Squadron, which led a devastating attack on a Spanish fleet in Manila Bay that destroyed every enemy warship without the loss of a single American vessel. This stunning victory brought both Commodore George Dewey (1837-1917) and his flagship national recognition. The Olympia was eventually retired in 1922 to the Philadelphia Navy Yard, and in 1957 the Navy ceded the ship to the Cruiser Olympia Association, a nonprofit organization established to acquire Olympia artifacts and raise funds for the boat’s preservation. Docked at Penn’s Landing, the next year the ship opened to the public as a floating museum.

The Spanish-American War lasted little more than three and a half months, but its legacy lived on in the Philadelphia region for years. In many ways, the conflict with Spain served as a rudimentary rehearsal for America’s next war, World War I (1917-18). The martial spirit and patriotism displayed in 1898 revived and grew in 1917 as tens of thousands of local men answered the call to join the Army and Navy. The ethos of military production that powered the region’s economy during the Spanish American War intensified during the Great War, and area civilians endured even more severe privations. The Spanish-American War had prepared the region to proceed and persevere through the First World War.

Paul A. Kopacz is the recipient of a master’s degree in history from Villanova University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- PhilaPlace: Cramp Shipyard — “A Community Organization and a Community Institution” (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- William Cramp & Sons Ship and Engine Building Company (The PhillyHistory Blog)

- The Philadelphia Peace Jubilee of 1898 (The PhillyHistory Blog)

- League Island before the Navy Yard (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- The World of 1898: The Spanish American War (Library of Congress)

- American Imperialism: The Spanish American War Primary Source Set (Digital Public Library of America)