Taverns

By Stephen Nepa | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

From small operations in the colonial era to elaborate social spaces in the twenty-first century, taverns in and around Philadelphia have been vital institutions, offering respite, nourishment, and camaraderie to travelers and patrons. Over time, attitudes and laws regarding the consumption of alcohol altered the character of the tavern and gave rise to modern hotels, restaurants, and bars.

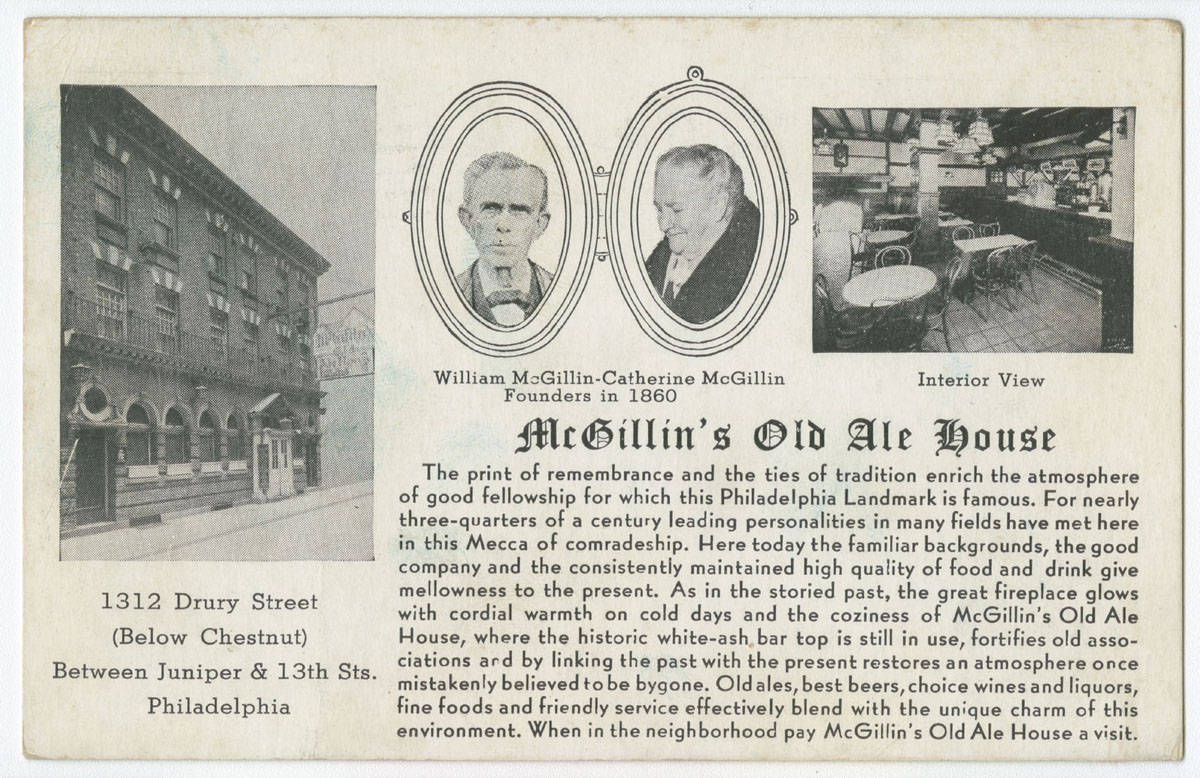

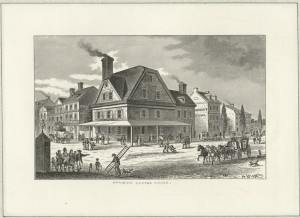

Early taverns, also known as public houses, inns, or ordinaries, provided travelers with lodging, meals, and social interaction. Philadelphia’s first, the Blue Anchor, appeared in 1681. By 1744, the city contained more than one hundred taverns and an unknown number of illegal tippling houses, leading a Grand Jury to demand licensing and maximum prices for alcohol. License applicants often were impoverished men and women whom magistrates viewed as unable to uphold the law. Yet because of the city’s tendency to ignore licensing requirements, critics of the law judged the policy as a failure. Taverns also appeared in many surrounding towns before 1800, including the Ferry Tavern in Camden, Wonderly’s Inn in Fort Washington, the Almonesson Inn in Deptford, Jessop’s Tavern in New Castle, and Daveis’ Tavern in Chews Landing. These early taverns usually were male-owned and served as places for discussions of politics, trade, and culture among merchants, statesmen, free Black people, laborers, and the clergy.

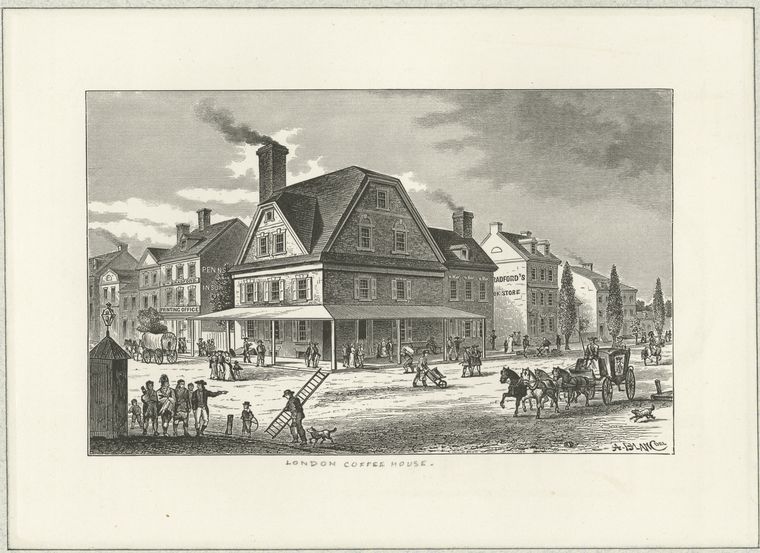

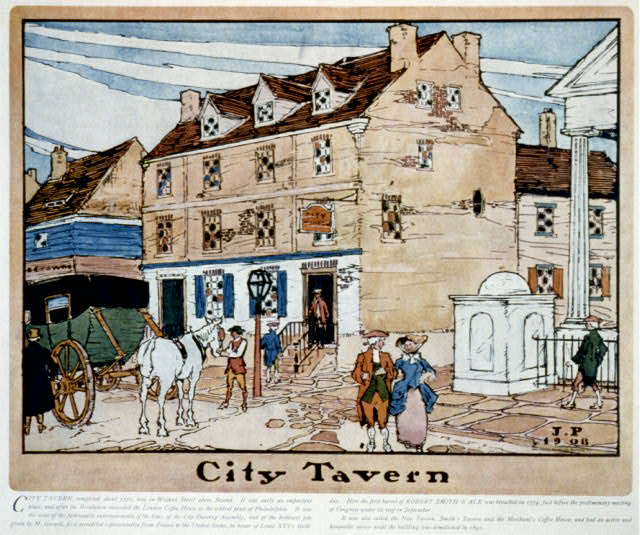

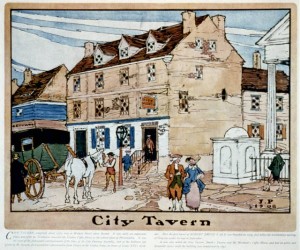

As the region grew, tavern patrons separated along class lines; merchants gathered at the London Coffeehouse, the political elite sipped Madeira at the City Tavern, stevedores and sailors frequented the Four Alls for pints of ale, and farmers patronized country inns. In many taverns, serving slaves or Native Americans was frowned upon. Along with these distinctions, medical professionals, enlightened thinkers, and lawmakers believed that taverns and even drinking itself threatened public health.

Taverns Yield to Hotels

After independence, taverns’ communal lodgings and washbasins fell out of favor with the rise of hotels. In 1790, Oeller’s Hotel, Philadelphia’s first, opened on Chestnut Street. Offering higher degrees of privacy and cleanliness, hotels minimized the lodging aspects of taverns. Yet even after the national capital shifted to Washington, new taverns continued to appear. By the mid-1820s, Philadelphians on average consumed annually 9.5 gallons of hard liquor plus 30.3 gallons of hard cider. With many drinking establishments in and around the city, a temperance sensibility, first articulated in the 1780s by prominent physician Benjamin Rush, took shape in Philadelphia.

In the 1840s, the region’s expanding factories required ever more workers, many of whom were newly arrived immigrants. This growth increased the variety of spirits available in taverns, including Irish stouts and ales, Scottish whiskies, and German beer. Over time, as more immigrant groups arrived, their Old World drinking habits changed as they were exposed to American practices. Yet the growth also sharpened socioeconomic inequalities. To alleviate the miseries of the poor, many taverns provided glasses of rum for a single penny. By 1841, Philadelphia contained more than nine hundred licensed taverns. Social reformers worried about masses of workers drinking cheaply and engaging in immoral behavior. The temperance movement strengthened to more than twenty active groups totaling 7,000 members. In 1854, Timothy Shay Arthur (1809-85) penned Ten Nights in a Bar Room. Based on his observations of Philadelphia’s taverns, Arthur’s novel served to further demonize alcohol.

Following the Civil War, temperance received new attention. Progressive reformers linked drinking to deviant conduct while factory owners felt concern about inebriated workers. By the 1880s, the tavern had devolved into the saloon, a drinking hall devoid of lodging spaces. Saloon owners offered basic food items such as meats, bread, and Delaware oysters to entice their patrons to drink more. The preferred venue of the working classes, the saloon was a highly masculine forum for labor organizing, cashing paychecks, mailing letters, and learning about immigrant assistance programs. Activities such as gambling, boxing, billiards, and chess were conducted by patrons. But saloons also were the target of temperance advocates, who sought to stop excessive drinking as well as corrupt associations between liquor interests and machine politics. Once in office, elected officials relied on saloon owners and the liquor industry to deliver the saloon vote. Conversely, saloon voters depended on those elected officials for jobs and favors. These dubious connections enraged groups such as the Anti-Saloon League and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). Reformers charged that saloons promoted crime, divorce, absenteeism from work, and alcoholism. Yet drunkenness was in reality less of a problem, as the majority of Philadelphians spent on average less than five percent of their annual income on liquor. To encourage employees not to frequent saloons, area businesses sponsored baseball teams, bicycling clubs, and excursions to the Willow Grove amusement park or the Jersey shore. Regarded as wholesome activities, these overtures were seen by many as introductions to middle-class respectability.

Enter the Speakeasy

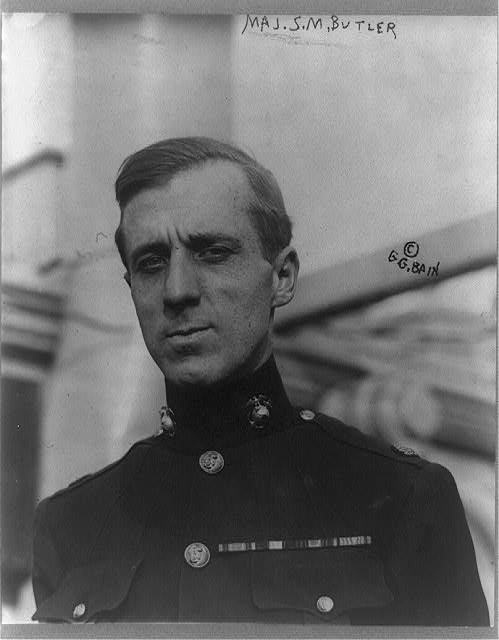

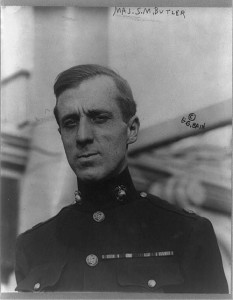

With the onset of Prohibition, the legalized saloon became the illegal speakeasy. In 1923, the Philadelphia police estimated that some eight thousand speakeasies sold alcohol. In some cases, fire companies assisted the police with raids. Speakeasies and restaurants reopened soon after authorities left while judges reluctantly imposed even small fines. Entrenched corruption among the police, politicians, and bootleggers made enforcement a daunting task. One of the most visible campaigns to rid the city of speakeasies fell upon General Smedley Darlington Butler, who in his first two days as Philadelphia’s Director of Public Safety suspended four police lieutenants and in his first year shuttered nearly 2,500 illegal liquor establishments. But by the mid-1920s, Prohibition in Greater Philadelphia had largely failed, with some 428,700 gallons of liquor released in the city every month. Several groups, including the Molly Pitcher Club and the Organization for Prohibition Enlightenment, worked actively for repeal. In New Jersey, one of three states that did not ratify the Eighteenth Amendment, the urbanized areas near Philadelphia contained numerous speakeasies where enforcement was virtually non-existent while breweries and distilleries appeared in rural locales.

When Prohibition was dismantled in 1933, Pennsylvania and New Jersey adopted liquor control to monitor the trade and reduce corruption. Illegal speakeasies gave way to taprooms. In Pennsylvania, municipalities were allowed one licensed taproom for every one thousand residents. Based on 1940 population figures, Philadelphia was permitted to have 1,951 licensees. When an actual tally was conducted, results showed that the city exceeded that amount by nearly nine hundred. After World War II, vice squads routinely raided taprooms suspected of housing gambling rings, selling to minors, or being linked with organized crime. In New Jersey, some cities remained dry while others such as Camden were inundated with liquor licensing requests.

As Greater Philadelphia suburbanized in the 1950s and 1960s, modern restaurants, hotels, and shopping malls emerged as places for middle-class commerce and socialization. The city meanwhile saw its bars and restaurants suffer due to laws banning the sale of alcohol on Sundays. Not until 1971, when Sunday sales finally were permitted, did Philadelphia’s bar and restaurant industry begin developing a national reputation. Following the Bicentennial in 1976 and deindustrialization, Greater Philadelphia’s economy shifted from manufacturing to one dependent upon service and entertainment. By the 1990s, the city and its suburbs contained numerous gastropubs, sports bars, ultra-lounges, wine bars, nightclubs, restaurants, and hotels, all of which sold alcohol. While the greater Philadelphia tavern in its colonial incarnation had ceased to exist, and the industry segmented along racial and class lines, the socialization that took place within them remained.

Stephen Nepa teaches history at Temple University and Rowan University. He is the author of “The New Urban Dining Room: Sidewalk Cafes in Postindustrial Philadelphia,” Buildings & Landscapes: Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum (Fall 2011), contributing author to A Green Country Towne: Art, History, and Ecology in Philadelphia (Penn State University Press, due 2014), and has written for Planning Perspectives, Essays in History, and Hospitality and Society. He received his M.A from the University of Nevada, Las Vegas and his Ph.D. from Temple University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Brewerytown going back to its sudsy roots (WHYY, January 9, 2014)

- Few Pa. taverns ready to take a chance on barroom gambling (WHYY, February 19, 2014)

- Tavern gaming glitch may have cooled Pa. expansion efforts (WHYY, April 15, 2014)

- Pa. lowers fee to boost taverns' interest in gambling (WHYY, August 3, 2014)

- Beers, bars and babies: The next generation of Philly school parents gets serious (WHYY, November 20, 2014)

- Pa. House GOP not keen on later bar closings (WHYY, April 20, 2015)

- Yards Brewing Company to celebrate 20 years with a toast to its humble beginnings in Manayunk (WHYY, May 14, 2015)

- Liquor-by-the-drink tax generates $60 million for Philly schools, revenue chief says (NewsWorks, June 3, 2016)