Thanksgiving

Essay

Although inspired by a 1621 feast shared by Pilgrims and Native Americans in Plymouth, Massachusetts, Thanksgiving traditions emerged from more than two centuries of celebrations influenced by social classes, ethnic groups, and the rise of consumer culture. Some of the most popular practices of Thanksgiving by the twenty-first century originated in Philadelphia.

In colonial America, days dedicated to giving thanks occurred at various times throughout the year and often reflected the traditions and desires of the regions that observed them. The end of the Revolutionary War provided ample opportunity for celebration across the new Republic, and days of public thanks-giving were declared nationally and locally. In Philadelphia, the Continental Congress declared a day of thanks-giving in October 1781 to honor the recent victory at the Battle of Yorktown and again on December 11, 1783, to celebrate the peace treaty and the formal end of the war. For the 1783 celebration, the Committee of Arrangements asked Charles Willson Peale (1741-1827), one of Philadelphia’s most popular artists, to create a triumphal arch “illuminated by about twelve-hundred lamps” to stand outside the State House as the celebration’s center piece. Although delayed by a fireworks accident that damaged the work in progress, by 1784 the completed arch “afforded great satisfaction to many thousand spectators.”

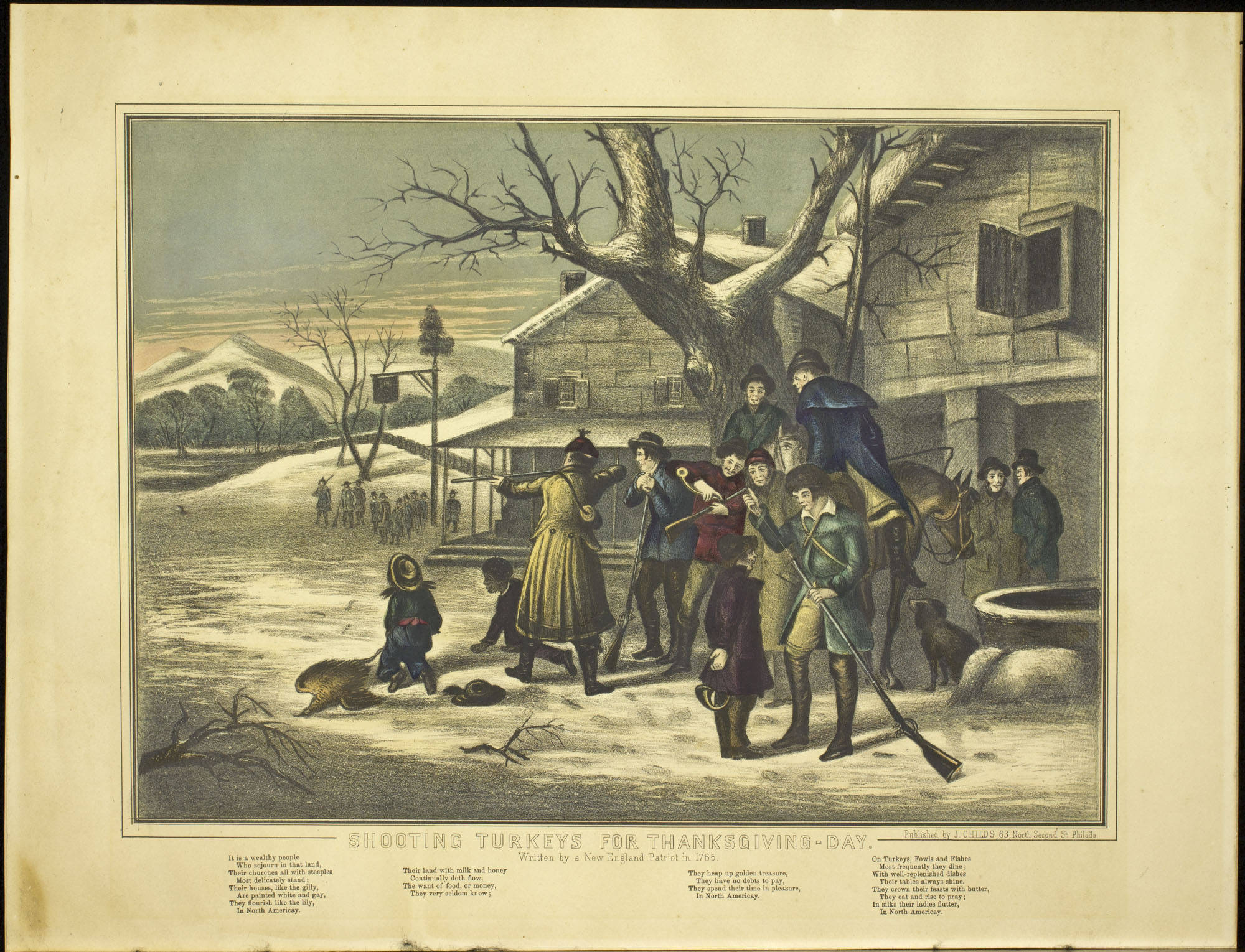

During the 1790s, while Philadelphia served as capital of the United States, Presidents George Washington (1732-99) and John Adams (1735-1826) issued ad hoc declarations for national days of thanks-giving. However, in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, it was more common for states, cities, or other localities to hold thanks-giving celebrations in their own ways at any given time during the year. Philadelphia’s upper- and middle-class families celebrated days of thanks-giving in ways similar to New Englanders, by having small family dinners and attending church services to thank God for the blessings in their lives. Working-class Philadelphians developed a reputation for rowdy, drunken, carnivalesque street celebrations. The parading groups, who called themselves Fantastics or Fantasticals, were often of Irish or English background and copied many of the English mumming parade techniques. For the most part, the upper classes accepted the parades and enjoyed watching, if not partaking in, the festivities through most of the nineteenth century.

Thanksgiving Campaign

Support for a national Thanksgiving holiday grew from a campaign launched by Sarah Josepha Hale (1788-1879), editor of the Philadelphia-published Godey’s Lady’s Book. Hale, a native of New Hampshire who became the magazine’s editor in 1837, believed that a national day dedicated to giving thanks might unify the country at a time of intensifying sectional divisiveness. Using her position at the popular monthly publication, Hale wrote to governors across the country and in U.S. territories to make a case for a holiday celebrating “the gratified hospitality, the obliging civility, and unaffected happiness of the American family.” Initially, Hale’s efforts did not do much to boost support for the domestic holiday. By the 1850s only New England, the Mid-Atlantic, and the state of Texas regularly celebrated.

Hale’s initiative achieved success in the midst of the Civil War, in the aftermath of Union victory at the Battle of Gettysburg. In October 1863, President Abraham Lincoln (1809-65), whom Hale had been petitioning for years, declared a national day of thanksgiving to take place each November. Although Southern states took longer than Northern states to accept and participate in the new national tradition, Thanksgiving became increasingly popular, and Hale’s vision for a domestic holiday centered on family and home life took root.

As the holiday took on a more sober tone, members of the upper classes became increasingly upset by the loud, drunken celebrations of the working class in cities like Philadelphia and New York. Among wealthier individuals, organized football games became an alternative to rowdy parades. The first Thanksgiving Day football game, played between the Young American Cricket Club and the Germantown Cricket Club, took place in Philadelphia in 1869. A few years later, the Intercollegiate Football Association scheduled its first championship game for Thanksgiving Day in 1876. By the turn of the century roughly 10,000 college and high school football teams were playing games on Thanksgiving Day. In Philadelphia, rivals Central High School and Northeast High School competed for the Wooden Horse Trophy on Thanksgiving Day. This annual competition began in 1892 and continued into the twenty-first century as Philadelphia’s oldest high school rivalry. In Southern New Jersey, Palmyra High School and Burlington City High School have been rivals since 1908 and have competed on Thanksgiving Day since the 1930s.

The Holiday Becomes Secularized

By the early twentieth century, Thanksgiving traditions were firmly embedded in American culture. The Catholic Church initially opposed the celebration of Thanksgiving as a Protestant religious holiday. However, the holiday became secularized as new groups of immigrants arrived during the early twentieth century. Schools taught Thanksgiving traditions to children, whose families then reinforced their American identities by participating in the national observance and demonstrating their allegiance to American culture.

By the 1920s, Catholic and Jewish households readily accepted the holiday, and intertwined their own religious practices, like service to the poor, with the Thanksgiving Day tradition. Immigrant families infused the traditional meal of roasted turkey with their own contributions by introducing new side dishes and cooking styles. Some Chinese American families steamed their turkeys and then stuffed them with traditional rice mixtures, while Greek families added pine nuts and spices to their stuffing and many Italian families enjoyed seafood and pasta dishes.

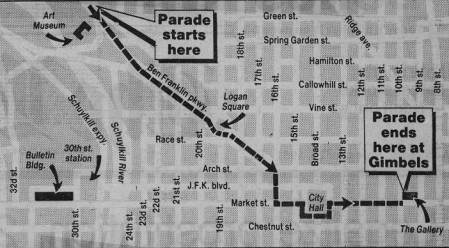

As the holiday grew in popularity, new traditions emerged. The first formal Thanksgiving Day parade, held in Philadelphia in 1920, marked the beginning of the holiday’s commercialization and cemented its ties to the Christmas season. Eager for the Christmas shopping season to begin, Ellis Gimbel (1865-1950) of Gimbels Department Store organized the first parade to lead shoppers from City Hall to the store at Ninth and Market Streets. In the grand finale, Santa Claus climbed a ladder into the building, where he greeted children eager to give him their wish lists. The Gimbels parade influenced Macy’s to begin its own parade in New York City in 1924, and by the mid-twentieth century Thanksgiving Day parades, often sponsored by department stores, became a tradition in towns and cities across the country. Over the next few decades Thanksgiving became increasingly commercialized as the official beginning of the Christmas season. By the second half of the twentieth century, the following Friday became known as “Black Friday” among retailers and consumers, and many stores offered large discounts and one-day sales to kick off their holiday shopping season.

New Parade Sponsors

As department stores declined in popularity the Thanksgiving Day Parade continued, but with new sponsors, routes, and audiences. After Gimbels closed in 1986, Philadelphia television station WPVI (6ABC) took over production of the parade. The parade retained its commercial character from sponsorship by Reading, Pennsylvania-based department store Boscov’s from 1986 to 2007; IKEA (a Swedish company with a flagship store in Conshohocken) from 2008 to 2011; and Dunkin’ Donuts beginning in 2011. However, its route shifted away from Philadelphia’s traditional Center City business district to the Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Culminating at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the televised event provided ample marketing opportunities for sponsors and advertisers seeking to reach the estimated 500,000 households tuning in to watch the 3.5-hour parade. Around the region, many stores opened earlier and earlier to accommodate Black Friday shoppers. With so many retail employees required to report to work on Thursday evening, many families celebrated in the late morning or chose to celebrate on a different day.

A reflection of American values, Thanksgiving Day traditions evolved over time while still retaining the initial celebratory, familial, and domestic themes of the original thanks-giving feasts. Philadelphia, a city of many firsts, contributed many innovations to Thanksgiving Day traditions as they came to be practiced across the nation.

Mikaela Maria is an editorial, research, and digital publishing assistant for The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. She received her M.A. from Rutgers University and works as a public historian and museum professional in Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- A Thanksgiving tradition continues at Mifflin Elementary (WHYY, November, 23, 2011)

- Pilgrims and parades: A brief history of Thanksgiving (WHYY, November 24, 2011)

- Thanksgiving travel’s carbon footprint covers a lot of territory (NewsWorks, November 25, 2015)

- Veggies take the spotlight with leftover recipes from chefs Jacoby and Landau (WHYY, November 24, 2016)