Twin Houses

By Anne E. Krulikowski | Reader-Nominated Topic

Essay

Semi-detached or “twin” houses, sometimes referred to as “doubles,” began appearing in the Philadelphia region in the mid-nineteenth century and were constructed in significant numbers until World War II, after which the GI Bill and spacious suburban tracts spurred on construction of detached houses. While neighborhoods had blocks built entirely with detached homes or row houses, developers almost always mixed in twins to provide for all economic levels of the private housing market. Housing reformers considered modest-sized twins to be an affordable alternative to detached dwellings. Although originally considered a suburban housing type in the United States, twins came to be regarded as a form of urban housing over the course of the twentieth century.

The English “semi” significantly influenced the development of the American twin. With a long history that probably dates back to the Roman occupation, the English semi in the early twenty-first century accounted for almost one-third of all housing in England, followed by detached, terraced (row) houses and apartments. Not only were semi-detached dwellings common urban dwellings, they became used in housing reform schemes. English landowners began constructing double cottages for farm laborers in the early nineteenth century. By mid-century, housing reformers were designing and building modest semi-detached dwellings for urban workers. In late nineteenth-century England, model villages such as Lever Brothers’ Port Sunlight (begun in 1887) and the Cadbury Company’s Bournville (begun in 1893) typically included semi-detached houses as the middle tier of a carefully planned hierarchy of housing: detached houses for managers, semis for junior managers and key workers, and row houses (terraces) for laborers. These villages became models for garden cities, promoted by English planner Ebenezer Howard (1850-1928), which in turn influenced many twentieth-century Anglo-American suburbs and planned communities.

Twins as Suburban Dwellings

In the Philadelphia region twins—or at least two dwellings attached to each other—occasionally appeared in the early nineteenth century, such as the early semi-detached dwellings on the King’s Highway and on Centre Street in Haddonfield, New Jersey. However, the twin began to emerge as a significant component of regional housing stock with the arrival of the omnibus in the 1830s and streetcars beginning in the 1850s. Although relatively pricey, these forms of public transportation provided the means for increasing numbers of middle-class families to escape congested areas of towns and cities and join the wealthy in commuting to and from newly developing outlying suburbs.

In Philadelphia, the earliest twins may have been the homes for wealthy and middle-class families in the first suburban developments of West Philadelphia, which until about 1850 remained a mainly rural environment of summer estates and mansions with small clusters of working-class families along the major highway to Baltimore. By mid-century, an omnibus ran from near the railroad station at Market Street into the central city at fifteen-minute intervals from early morning until late evening. In 1851, developers hired Samuel Sloan (1815-84), architect of fashionable mansions, to design West Philadelphia dwellings to appeal to a market of both well-heeled and solidly middle-class families. The twin, when combined with detached dwellings or row houses, created mid-nineteenth century residential districts that were not as socioeconomically segregated as they subsequently became; even one block could be planned to appeal to some variation of incomes.

Sloan’s first dwellings for the West Philadelphia project consisted of four pairs of semi-detached houses and two larger single dwellings. Clearly, neither the developers nor the architect believed that families who could afford the larger detached houses—advertised as picturesque dwellings in an English Gothic style—would be put off by the adjacent and more modest twins. In fact, Sloan designed large detached houses for the project’s developers on blocks of mixed detached and twins. Twins did often signal more modest means, though. When horsecar lines replaced the Market Street omnibus in 1858, streets traversed by the horsecars exhibited a more intense development of exclusively twins and rows.

Italianate Twins

At Hamilton Terrace, an extension of Forty-First Street beyond Baltimore Avenue to Chester Avenue, Sloan designed another group of houses. His Italianate twins were marketed as “double villas,” a dwelling type then associated with suburbs. Their floor-to-ceiling windows opened onto porches, similar to the amenities typically found in homes of the wealthy. Even within one block, the size and amenities offered by twins could vary significantly. At Hamilton Terrace, the six pairs of semi-detached dwellings on the eastern side of the street occupied smaller lots than those on the facing side, where families enjoyed more space. On both sides, a few single dwellings were mixed in, again demonstrating the twin to be a dwelling type that accommodated many levels of the housing market. With some architectural style, more interior square footage, and a larger lot, the twin was considered suitable for the “best” neighborhoods.

Twins continued to figure prominently in the transformation of West Philadelphia into a professional and upper-class suburb. In the early 1860s, an investor subdivided Woodland Terrace, one block east of Hamilton Terrace, into twenty-two lots to accommodate eleven pairs of semi-detached dwellings. To protect the suburban middle-class landscape, deed restrictions forbid nuisance industries. Indeed, by 1870 the heads of these households were predominantly merchants who owned stores or wholesale offices downtown and most had servants. Later upper-class neighborhoods in this vicinity, such as Satterlee Heights and Powelton, continued to feature many twins.

The versatile twin houses quickly gained popularity, but they were never so popular that entire communities of twins appealed to people, which distinguishes them from detached and row houses. One suburban venture in the 1850s, though, attempted to create a suburb including only twin dwellings. The Haddonfield Ready Villa Association, a group of investors with ties to the Pennsylvania Railroad, planned to create a new Philadelphia suburb in Haddonfield, New Jersey. To attract Philadelphians, the developers hired the well-known Samuel Sloan, who planned only twin houses, although prospective residents could choose to have any model built as a detached dwelling. Philadelphians do not seem to have been interested in moving to Haddonfield at that time, although a few commuters already resided there, and the failed suburb left no record regarding the appeal of an all-twin residential community. As urban transportation networks developed in the mid- and late-nineteenth century and spurred on the subdivision of suburban tracts twins of various sizes became almost as typical suburban dwellings as detached houses in larger cities such as Wilmington and Camden, and smaller towns such as Phoenixville and Downingtown, Pennsylvania, and Woodbury and Haddon Heights, New Jersey, where twins were built in significant numbers until World War II.

Twins in Upper-Class Suburbs

The Overbrook Farms suburb developed during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries when suburbanization followed the new electric trolley lines along Lancaster Pike and Haverford Road and between 1880 and 1900 tripled the population in the northern portion of West Philadelphia. On the western edge of the city, Overbrook Farms developed from scratch as a tract featuring large detached and twin dwellings, many of which were mansionlike in size, for well-heeled families. Large lot sizes offered architects more scope for inventiveness with design elements such as door placements. For instance, Clarence E. Schermerhorn (1872-1925) designed a partly stone twin in which he located the two front doors on opposite walls, providing maximum privacy for the families occupying the twin dwellings.

Many of Philadelphia’s twins were the work of builders who copied plans from one job to the next and like many row houses cannot be traced to a specific architect. However, the importance of this housing type by the last several decades of the nineteenth century meant that many of the city’s most successful architects received commissions to design twins. Several of Philadelphia’s most successful architects at the time—Horace Trumbauer (1868-1938), Charles Barton Keen (1868-1931), Frank Mead (1865-1940), and William (1861-1916) and Walter (1857-1951) Price—designed twins for Overbrook and other suburbs on the fringe of the city, such as Pelham near Chestnut Hill. Elkins Park and Cheltenham, both in Montgomery County, featured twins along with mansions for the Philadelphia business elite and similar developments appeared throughout southeastern Pennsylvania. East Mount Airy, like early West Philadelphia a location for earlier summer homes for the wealthy, developed as an upper middle-class railroad suburb beginning in the 1850s, characterized by a mix of large detached and twin houses.

In Northwest Philadelphia, Dr. George Woodward (1863-1952) experimented with twins in the railroad suburb of Chestnut Hill. Writing for the Architectural Record, Woodward noted that Philadelphians considered twins to be quite respectable: “The Philadelphia suburban dweller suffers no loss of pride when he receives his friends in a semi-detached or in the Philadelphia colloquial phrase, ‘twin house’.” Many of the twins Woodward and his architects built during the 1910s and 1920s were actually intended as rental properties for the working class, but Woodward found younger middle-class “white collars” eagerly lined up to rent them.

Sometimes profit-hungry developers believed that even the most modest twins required too much physical space for rapidly developed neighborhoods near new transit lines that drove up land value. In westernmost West Philadelphia, the opening in 1907 of the Market Street Elevated Line, which promised to transport residents on the western fringe of the city to Center City in fifteen minutes, generated an explosion of population and construction while land values trebled from 1907 to 1915. Areas closest to the line, such as southern Haddington and western Mill Creek, developed most intensively with almost eight thousand houses, predominantly row houses, constructed in just those two sections alone between 1905 and 1915. A similar situation developed in Strawberry Mansion, where 90 percent of the housing stock consisted of small row houses, with few small twins mixed in. Likewise, the working-class Franklinville section, adjacent to upper-middle class and more spacious East Mount Airy in northwest Philadelphia, featured blocks of rows with quite small semi-detached houses at the upper end of the scale for that community. Even still, these humble brick two-story pairs set close to the street at first glance appeared to be row houses.

The section of the city most famously identified with monotonous blocks of small row houses on narrow streets, South Philadelphia, also became the location for a unique community composed almost entirely of semi-detached houses, the “ideal city homes” of Girard Estate. Stephen Girard (1750-1831) had left an estate including a large farm property in Passyunk Township to the city to fund Girard College, a school for orphan boys. To produce rental income for Girard College, the trustees of the estate hired architect James H. Windrim (1840-1919) and later his son, John Torrey Windrim (1866-1934), to create a neighborhood in Passyunk in the spirit of a garden city, although laid out on the Philadelphia street grid. From 1906 through 1916, the Windrims designed 256 semi-detached dwellings, one apartment building, and one block of row houses for rent to middle-class families of lawyers, doctors, bankers, and naval officers. The semi-detached houses included porches, front and backyards, and plenty of windows for light and air, creating a neighborhood markedly different from the endless blocks of brick rows surrounding it.

In addition to providing dwellings for many socioeconomic classes, twins provided opportunities for some idiosyncratic variations. George Woodward, who had introduced twins into Chestnut Hill, and other architects worried that the more modest twins, like row houses, contributed to the “curse of monotony” and such “defects” as unsightly backyards and crowding. In the 1910s, these concerns led Woodward and architects Duhring, Okie & Ziegler (active 1899-1918) to develop “quadruples,” or back-to-back twins. In England, back-to-back dwellings were associated with higher mortality rates, but Woodward, who was a trained doctor, reported at a National Housing Conference that no one had yet died while living in a quadruple in Chestnut Hill. Woodward mistakenly predicted quads would become as popular as twins, but only quadruples were occasionally built in the Philadelphia region. Much more common than quadruples were twin houses built to function as detached dwellings. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries families often purchased one or more lots in newly developing wards or newly developing suburbs and then self-built a twin house in the center, with one solid wall. For self-builders, the solid wall was quicker and less expensive to erect than a true detached house.

Twins for the Workforce

Twins also figured prominently in communities developed especially for workers. In these settings, though, architects and company town developers often used twins as part of a hierarchy of housing that indicated the relative value of workers in the workforce. After the Keasbey and Mattison Company moved to Ambler, Montgomery County, the company built four hundred houses, many of them twins, and community buildings for workers in the late nineteenth and early years of the twentieth centuries. Between the early 1870s and World War I, the Disston family created a residential community with twins for employees of their Keystone Saw factory in Philadelphia’s Tacony section. Detached and larger semi-detached dwellings were built for managers and professionals, such as doctors, while smaller twins provided housing for most wage workers. In Philadelphia, where worker housing typically meant unrelieved blocks of row houses set close to narrow streets, twins were a significant departure and provided room for grass and trees.

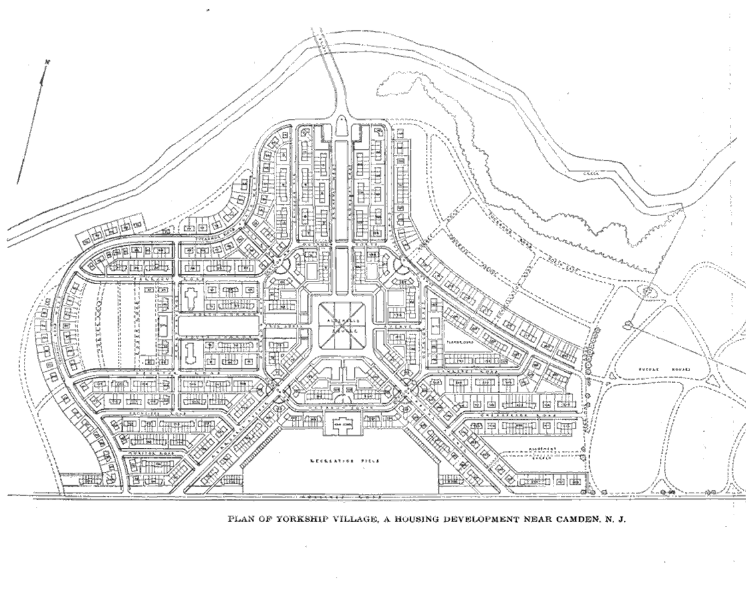

Semi-detached dwellings also predominated in the communities of modest housing created during World War I for the many defense and shipyard workers who came to the Wilmington-Philadelphia-Camden area. Seeking to create attractive residential landscapes for workers, architects and planners working for the Emergency Fleet Corporation designed twins for Yorkship Village (Camden); Sun Village, Buckman Village, and Sun Hill (Chester); Noreg Village (renamed Brooklawn, Gloucester); and Union Park Gardens (Wilmington). At Union Park Gardens, landscape architect John Nolen (1869-1937) and the Philadelphia firm Ballinger & Perrot (fl. 1901-1920) created a mix of row and semi-detached houses for shipyard workers. The quite modest twins included six rooms, the largest only 11.5 x 12 feet. However, curving tree-lined streets and a park created a pleasant garden suburb landscape for residents.

Despite the ideals of some architects, though, government-sponsored projects and company towns frequently designated dwelling types and sizes to represent hierarchies of skills and sometimes even nationalities in the workforce. The Emergency Fleet Corporation specified that semi-detached houses should be built only to Grade B standards and usually as rental housing. An example of a community built to such specifications was the Midvale Steel Company’s town in Coatesville, Chester County, built in 1916. Larger detached dwellings provided homes for superintendents and somewhat smaller detached dwellings housed skilled workers; semi-detached models were reserved for “foreign labor.”

Twins and the Automobile

As the automobile became a middle-class mode of transportation during the 1910s and 1920s, planners and architects also turned to twins to find spatial solutions to the reality of the automobile in new suburbs. Residential blocks near the new Cobbs Creek Parkway on the western edge of West Philadelphia became the city’s first auto suburb when in 1914 developers hired E. Allen Wilson (c. 1875-?), responsible for thousands of the city’s row houses, to design residences. For the north side of the 6200 block of Christian Street Wilson designed forty-four two-story twins with a narrow drive between each pair leading back to freestanding garages, thereby allowing for as many dwellings as possible on each block. On the south side, Wilson incorporated the garages at the basement level to be accessed from a rear alley. Several adjacent blocks developed similarly. In the 1920s, after developer Clarence Siegel (c. 1880-?) obtained a large parcel of land east of the Cobbs Creek vicinity, the Garden Court neighborhood took shape as a coherent residential community with many blocks of twin dwellings, all with rear garages accessed from alleyways.

From the 1920s through the 1950s, developers built large numbers of twins in new auto suburbs in Northeast Philadelphia, in Wilmington neighborhoods, in New Jersey towns, and many communities in Delaware County, Pennsylvania. In Upper Darby, for instance, the Warner-West Corporation, one of the largest developers in the nation, developed sections of that township with carefully planned areas of stone or brick and stone, semi-detached Tudor, Mission, and Norman style houses varying in size from six to eight rooms to relieve the density of more numerous blocks of row houses and court apartment buildings. With twins, side yards provided ample room for automobiles to reach detached garages in the back of the yards, still leaving a green space for trees, lawns, and gardens.

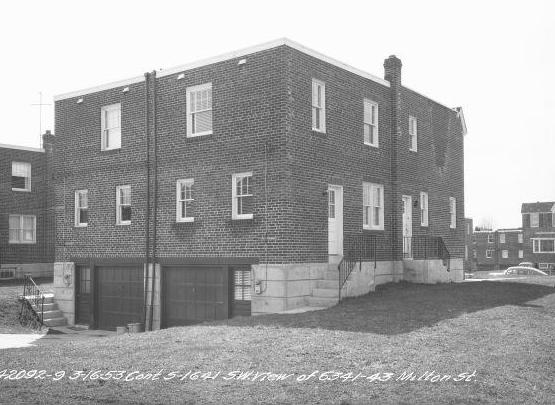

The popularity of automobiles eventually reduced the appeal of twins, however, especially when the garage migrated from the backyard into the house and newer suburban homes even offered two-car garages. A relatively rare 1960s design incorporated the garage into twin houses by placing the pair of dwellings over two single garages, so that the first floor of each dwelling was reached by a flight of steps outside; the garage door rather than the front door faced the street. Twins were conspicuously absent in post-war suburbs such as Levittown, Pennsylvania, and Willingboro, New Jersey. By the 1960s, long-term mortgages and low-interest mortgages for veterans brought spacious suburban lots and houses within reach of more families. Like row houses, semi-detached dwellings, which had originally been associated with middle-class suburban life, became identified with decaying cities. When located in more spaciously designed urban neighborhoods or others that gradually gentrified, the twin house, like the row, continued to appeal to those seeking an urban lifestyle.

In the early twenty-first century, twins once again made an appearance in new suburban communities around the nation, including the Philadelphia region. As house prices skyrocketed beyond the means of many families and others sought to downsize, a modest semi-detached house potentially offered a practical and more affordable alternative to larger detached dwellings in terms of reduced outdoor space to care for and the cost of mortgage, utilities, and furnishing. Instead, though, some early twenty-first century twins built near towns such as West Chester, Pennsylvania, and Newark, Delaware, were as lavish in square footage as many detached suburban houses, thus representing continuity with those early large twins built in upper-middle class suburbs such as Overbrook Park. Reducing time spent on outdoor chores and lawn care rather than budget constraints, seemed to be significant selling point of twin dwellings for this new generation.

Anne Krulikowski is Professor of History/Public History at West Chester University and has published articles on housing and suburbs, land use, and oral history. Her book, We Serve: West Chester University, 1871-2021, was published in 2022. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2022, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Links

- Decidedly Different West Philadelphia Twins (HiddenCity Philadelphia)

- Yorkship Village

- Overbrook Farms (West Philadelphia Collaborative History)

- Designations (Keeping Society of Philadelphia)

- Girard Estate (pdf, Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia)

- Clarence Siegel’s Garden Court: The Rowhouse Meets the Automobile (PhillyHistory Blog)