Walking Purchase

By Tim Hayburn

Essay

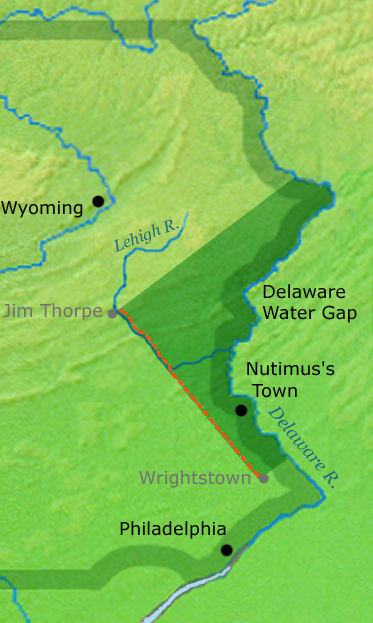

With the Walking Purchase of 1737, Pennsylvania officials defrauded the Delaware Indians out of a vast amount of land, perhaps over one million acres, in the Delaware and Lehigh Valleys. John Penn (1700-46) and Thomas Penn (1702-75), the sons of William Penn (1644-1718), with James Logan (1674-1751), the provincial secretary of Pennsylvania, devised the land grab by using an unsigned draft of a 1686 deed, obtaining support from the Iroquois and using trickery to take much more land than specified in the draft deed. The Walking Purchase represented a shift from earlier land transactions between William Penn’s government and the Delawares (also known as the Lenapes and Munsees) and paved the way for tensions that contributed to the Seven Years’ War.

After receiving a charter for Pennsylvania in 1681, William Penn sought to purchase the land in southeastern Pennsylvania from the Delawares, obtaining much of the territory before leaving the colony in 1684. His agents negotiated the purchase of land in central Bucks County in 1686, but the deed was unsigned because Penn failed to send enough trade goods to complete the sale. Penn had left the colony in part to address his financial problems and the purchase was never fully consummated.

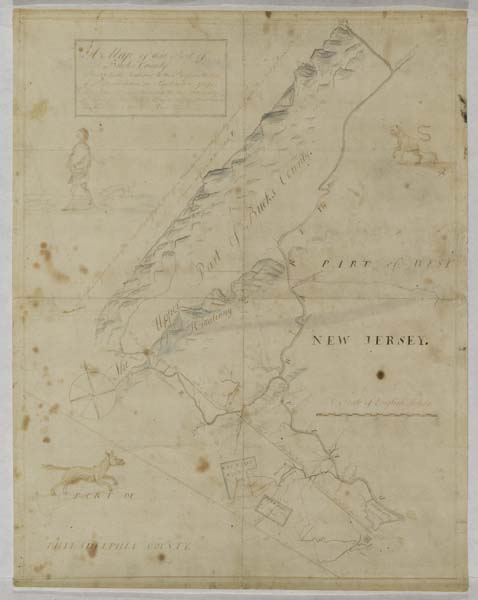

By the 1730s, the increasing population of Pennsylvania coupled with the growing debt of Penn’s heirs led the Penns and Logan to defraud the Delawares. Speculators, including Logan, had already purchased tracts of land in northern Bucks County and the Lehigh Valley, but needed an agreement with the Delawares before allowing settlement. Logan produced the unsigned copy of the 1686 deed, claiming that the Delawares had agreed to sell territory that a man could walk in a day and a half north from the boundary at Wrightstown. While the Delawares believed the new boundary would be Tohickon Creek in central Bucks County, Logan and the Penns aimed to obtain territory well beyond the Lehigh River. Historian Stephen Harper pointed out that the alleged deed lacked any signatures or evidence of payment, which weakened the proprietors’ claims to the land. Nevertheless, Logan met with Delaware sachems at Pennsbury and continued to press the proprietors’ claims.

Misleading Map

Logan worked for a rapid resolution to this situation at a series of meetings with Delaware sachems. Logan and Thomas Penn met with Nutimus, Manawkyhickon, Lapowinzo, and Tishcohan at Stenton, Logan’s county seat outside of Philadelphia, in August 1737. Manawkyhickon expressed a willingness to agree to the transaction if the sachems could learn how much land had been ceded to the proprietor in the draft deed. Andrew Hamilton (c. 1676-1741), an agent for the provincial government, produced a map, which misled the sachems into thinking that the purchase involved only territory south of Tohickon Creek. The sachems finally agreed to the transaction after being assured that the Delawares would not be removed from their settlements.

Unbeknownst to the Delawares, colonial agents had already performed a reconnaissance of the territory and cleared a path for the walkers. On September 19, 1737, three colonial walkers set off at a rapid pace; after one and one-half days one man covered over 60 miles. Surveyors acquired even more territory by angling the boundary to the confluence of the Delaware and Lackawaxen Rivers.

When the Delaware Indians protested the amount of land they lost in the Walking Purchase and refused to leave the region north of Tohickon Creek, the Pennsylvania government appealed to the Iroquois to help justify the transaction. Canassatego, an Iroquois spokesman, rebuked the Delawares for not complying with the purchase at a conference in Philadelphia in 1742. Over subsequent years, most Delawares in eastern Pennsylvania moved west to the Ohio River Valley and developed trade relations with the French. With the onset of hostilities in the Seven Years’ War, many Delawares sided with the French after General Edward Braddock (1695-1755) rejected their attempt to forge an alliance with the British. Consequently, the Walking Purchase reflected a shift from William Penn’s early diplomacy with the Delawares, alienating them from the British colonists by the mid-eighteenth century.

Tim Hayburn received his doctorate in colonial American history from Lehigh University. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University