Whig Party

Essay

The Whig Party thrived in the Philadelphia region from its founding in 1834 through its demise twenty years later. The party, which emerged from the National Republicans in opposition to Andrew Jackson (1767-1845) and his Democratic Party, claimed the Whig name from the patriots of the American Revolution. Whigs controlled Philadelphia government through electoral victories and circulation of Whig-leaning papers like the Philadelphia Inquirer and the North American during a tumultuous period of racial conflict, nativism, and the consolidation of the city with Philadelphia County.

Whigs often struggled from appearing to be little more than an opposition party to Jackson and the Democrats. Generally, though, Whigs championed Henry Clay’s (1777-1852) American System, a program of tariffs and internal improvements. They also supported a national bank to manage currency. The party achieved more success regionally than at the national level, finding issues that drew in voters. In the Philadelphia region, these included improvements to the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal (in which Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Maryland invested) and the widening of the Morris Canal in New Jersey. Throughout the era, Pennsylvania and New Jersey remained competitive statewide. Pennsylvania Democrats kept a strong hold on the state House of Representatives and governorship. Whigs sometimes controlled the state Senate. New Jersey Whigs ruled state offices from 1837 to 1848. Newark, Trenton, Elizabeth, Burlington County, and Jersey City were anti-Jackson strongholds. Camden County, which favored Democrats, formed from Whig-leaning Gloucester County in 1844. Delaware Whigs controlled Kent and Sussex Counties and sent a Whig delegation to Congress.

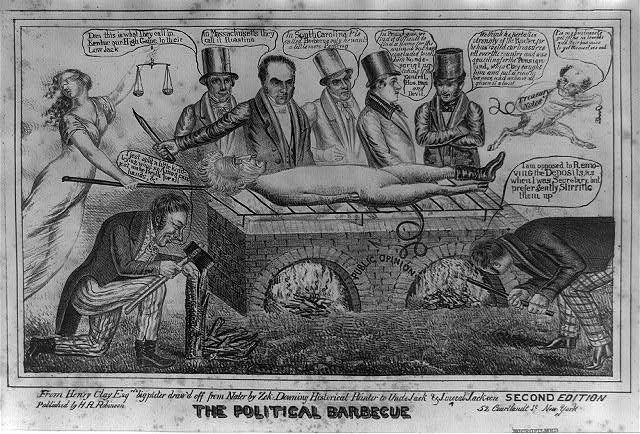

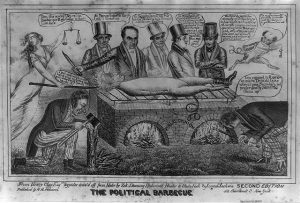

Philadelphia’s Whig Party developed from economic concerns and, as a result, appealed to voters of all socioeconomic groups. Although Pennsylvania supported Jackson in the 1828 presidential election, the president waged war against the Second Bank of the United States (headquartered in Philadelphia), protective tariffs, and internal improvements—all important to the commonwealth’s voters. Nevertheless, Jackson remained very popular despite his administration working against Pennsylvania’s interests. He lost Philadelphia in the 1832 election, but carried the state. He also won New Jersey, but the Garden State elected an anti-Jackson legislature. In congressional elections, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware all voted for candidates who opposed Jackson in the bank debate. In 1834, despite the early gains, anti-Jacksonians, by then called Whigs, lost seats in Congress and the Pennsylvania legislature, partly from the economic malaise that followed Jackson’s veto of a new charter for the national bank. The bank’s credit restrictions during the Bank War, Jackson’s popularity, and Election Day riots contributed to Whig defeats.

Riots and Nativism

Whigs saw both successes and challenges through the following years. Lawyer John Swift (1790-1873), a Whig, served as Philadelphia’s mayor for much of the 1830s. In 1839, he won reelection by popular vote, the first mayor so chosen (rather than by vote of the City Council). Racial conflicts marked Swift’s years as mayor. Many Whigs were anti-slavery; some leaned toward abolitionism. A riot in August 1834 became an election issue. Whigs claimed that Democrats in Southwark and Moyamensing started it for political reasons; Democrats countered that the riots resulted from the ineptitude of Whig governance and called for a combined city-county government. Swift was unsuccessful in preventing violence in 1834, and he failed again in 1838 when he lukewarmly tried to prevent anti-abolitionists from burning Pennsylvania Hall, built by abolitionist groups.

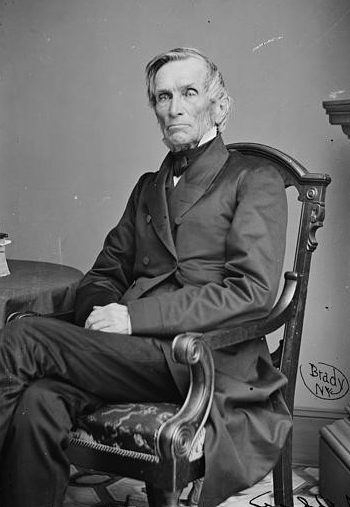

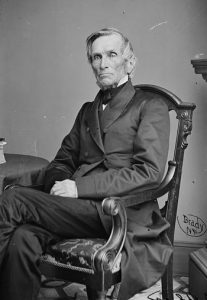

The city’s voters continued to back Whigs despite setbacks, hoping that their policies would lead to economic growth. Swift’s successor was John Scott (1789-1858), who led the city through additional turmoil as the Whigs became more associated with nativism (policies favoring native-born Americans over immigrants). In the summer of 1844, when nativist riots occurred in immigrant (particularly Irish) and Catholic neighborhoods, Scott tried to end to the violence. At St. Augustine Church on May 8, he pleaded with the rioters for peace to no avail. The mob hurled rocks at the mayor and burned the church. Such nativist violence likely cost the Whigs Philadelphia in the 1844 presidential election, when their candidate for vice president was former New Jersey Senator Theodore Frelinghuysen (1787-1862), a leader of the nativist, anti-Catholic American Bible Society. Whig President John Tyler (1790-1862) vetoed a national banking bill, further damaged Philadelphia Whigs’ election hopes, despite the fact that national leaders expelled Tyler from the party.

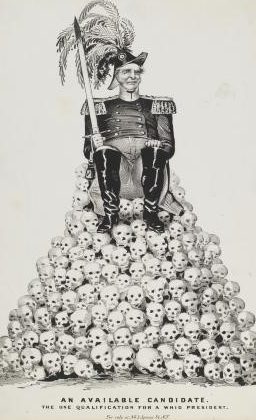

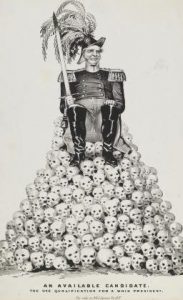

By the time Whigs convened in Philadelphia for their national convention in 1848, the party was splitting along sectional lines. In the aftermath of the Mexican-American War, many Whigs rallied around war hero Zachary Taylor (1784-1850). As a slaveholder, Taylor drew in some southern support. Some northerners backed Taylor, seeing him as a ticket to regaining the White House. Other northern Whigs backed Henry Clay. At the convention, which opened on June 7 in the former Chinese Museum building at Ninth and Sansom Streets, Pennsylvanians favored Taylor but New Jersey Whigs preferred Clay. Taylor ultimately defeated his divided opposition in four ballots. With Whigs actively seeking the nativist vote, Millard Fillmore (1800-74) received the vice presidential nomination. In the campaign, Whigs tried to lure working-class voters by blaming a recession on the 1846 Walker Tariff, which substantially cut duties. The bill was so unpopular that Philadelphians burned city native Vice President George M. Dallas (1792-1864) in effigy for casting the tie-breaking vote. Philadelphians, regardless of class or party, believed tariffs to be economically beneficial to the city’s businesses. This matter helped to put Pennsylvania into the Whig column. Taylor also comfortably won New Jersey and Delaware on his way to defeating Democrat Lewis Cass (1782-1866) and Free Soil candidate Martin Van Buren (1782-1862) for the presidency.

City-County Consolidation and Demise

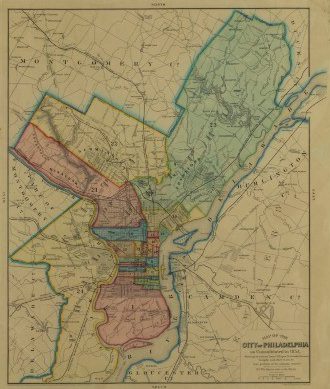

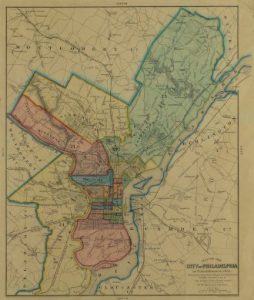

Through the 1840s, Philadelphia Whigs and Democrats debated the idea of consolidating the city (then bounded by South Street, Vine Street, and the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers) with Philadelphia County. The 1844 nativist riots called attention to the need for greater law enforcement in the city’s suburbs. Whigs, who controlled the city through the decade, opposed merging with the Democratic-leaning county. After years of effort in the legislature, on February 2, 1854, Democratic Governor William Bigler (1814-80) signed the Act of Consolidation that joined the city with Philadelphia County. It set up twenty-four wards with a mayor serving a two-year term. Despite the expanded territory of the city, Whigs retained control of the mayor’s office as a coalition between Whigs and Know Nothings (a nativist political movement) elected Robert T. Conrad (1810-58), a businessman, judge, and playwright, the first mayor after consolidation.

While nativism propelled Conrad into elected office, it ended the career of another Whig politician, Joseph Chandler (1792-1880). He served on the City Council from 1832 until 1848, when he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. He also helped the Whig paper Gazette of the United States gain some national attention. Highly respected by Philadelphians because of his work to improve the city, he was not renominated in 1854, he believed, because of his conversion to Catholicism. His supporters blamed Know Nothing influence in the faltering Whig Party.

Many identified as Whigs because of politics or economics, but a reformist movement within the party contributed to its demise. Nationally, the Whig Party splintered over sectional tensions—particularly over slavery. The Compromise of 1850 and the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 divided Whigs in Congress. After New Jersey’s two Whig senators voted against the Compromise of 1850, voters replaced them with conservative, unionist Democrats. In Delaware, the party’s antislavery wing pushed for an abolition bill that narrowly failed in the legislature. Upper-class Protestants steered the party toward nativism, advocacy for temperance, and high tariffs, which hurt the party among immigrants, Catholics, and the working class. Philadelphia voters split between the American Party (which formed from the Known Nothing movement), the new Republican Party, and the People’s Party (which avoided the slavery issue but was ideologically similar to the Republicans). By the early 1860s, the city was becoming a Republican stronghold.

The work of the Whigs’ elder statesman, Henry Clay, on measures such as the Compromise of 1850 gained for the party a reputation for compromise and union. Long after the demise of the nineteenth-century Whigs, this legacy inspired the Modern Whig Party, a centrist, grassroots movement founded in 2007 with the goal of luring voters disenchanted with the Republicans and Democrats. In 2013, a candidate running under this revived Whig banner, Robert Bucholz (b. 1974), won election as a Judge of Elections in Philadelphia’s 56th Ward. He was the first Whig elected to an office in nearly 160 years since Whigs dominated the region’s politics.

Andrew Tremel is an independent researcher and public historian at the U.S. Capitol Visitor Center. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Backgrounders

Links

- Web Guide to the Compromise of 1850 (Library of Congress)

- The Modern Whig Party

- Who Shall Be Mayor? (Library of Congress, 1854, PDF)

- Philadelphia's early convention history: Whigs, Know-Nothings, and a young GOP (National Constitution Center)

- PhilaPlace: Whig Party Convention of 1848--The Chinese Museum of Philadelphia (Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

- Theodore Frelinghuysen (Biographical Directory of the U.S. Congress)

- The Whig Almanac, and Politician's Register, for 1838 (Google Books)