City Hall (Philadelphia)

Essay

Constructed over a thirty-year period at a cost approaching $25 million, Philadelphia City Hall stands as a monument both to the city’s grand ambitions and to the extravagance of its political culture. Controversial from the outset–for its location, its architecture, and the patronage it commanded on behalf of its construction–the structure nonetheless came to be embraced over time as a distinctive emblem at the heart of a great city.

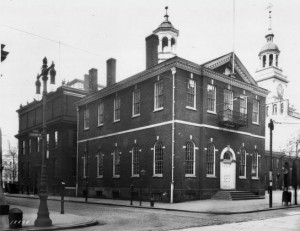

The massive masonry structure owes much to the consolidation of city and county in 1854. In doubling the city’s population to 565,000 people, consolidation required the expansion of services that outstripped the capacity of the two-story building at Fifth and Chestnut Streets, designated in 1791 as the city’s second city hall. As early as 1838 the Pennsylvania legislature recognized the need for new municipal offices, but disagreements focusing largely on the location of the new structure prevented action until the 1870s. In 1871 the question of location was put to popular vote, with the result favoring Penn Square to the west, where the city was expanding, over Washington Square at the heart of the city’s early commercial center.

The grand scale of the new structure reflected the city’s aspirations—futile in the end—to reassert its position at the top of the American urban hierarchy. Seeking to attract a leading architect for the project, the city sponsored several competitions, ultimately awarding the commission to 39-year-old Scottish-born John McArthur (1823-90), whose buildings in the city had included the Wagner Free Institute of Science (1859) and the Public Ledger (1866). It did not hurt that he received coaching from Thomas U. Walter (1804-1887), architect of the U.S. Capitol from 1851 until 1865, with whom McArthur had trained. Walter subsequently served as a paid consultant to the project.

Second Empire Style

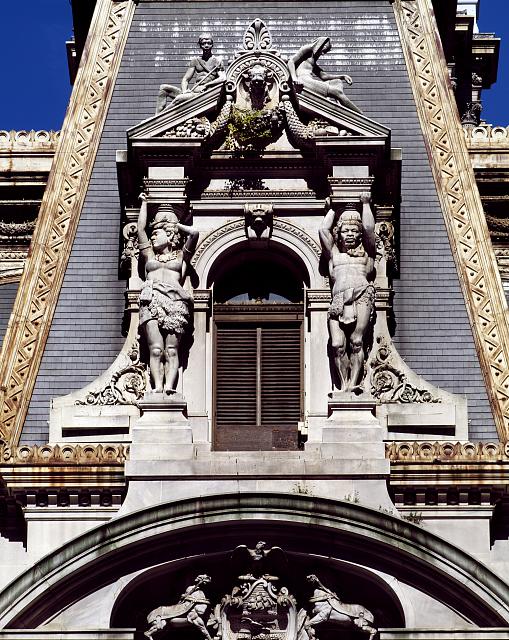

Cast in the fashionable French Second Empire style—the same style simultaneously embraced for the structure later known as the Old Executive Office Building in Washington, D.C.—City Hall mixed thick masonry construction, up to 22 feet in some places, with elaborate ornamentation inside and out. Intended to be the highest building in the world, with its bell tower topping at 548 feet, by the time the building was completed in 1901, it had been surpassed by the Washington Monument and the Eiffel Tower. Still, it could claim to be the world’s largest occupied structure until it was surpassed by New York City’s Mutual Life building in 1909. By gentlemen’s agreement, no other building role above City Hall in Philadelphia until 1987 with construction of One Liberty Place.

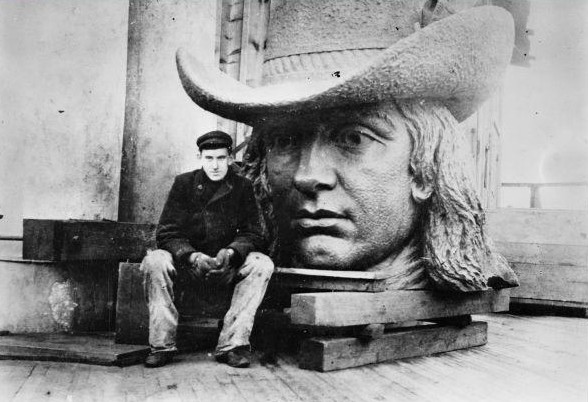

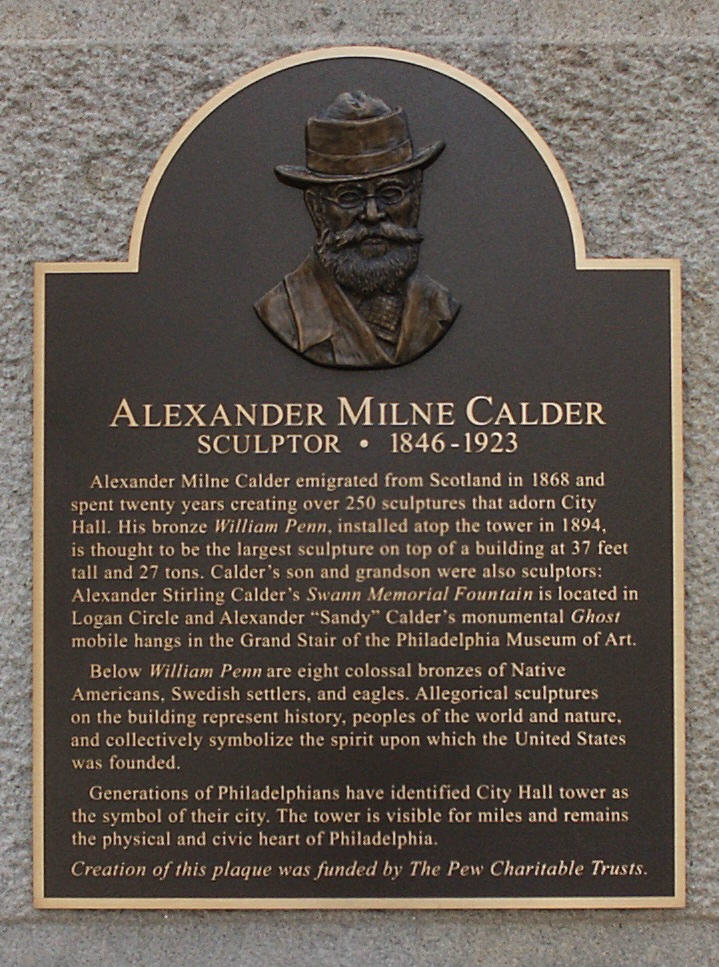

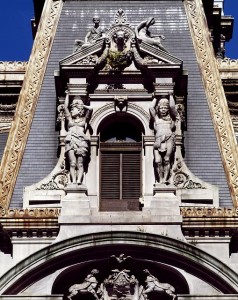

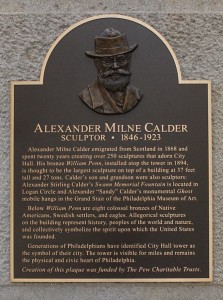

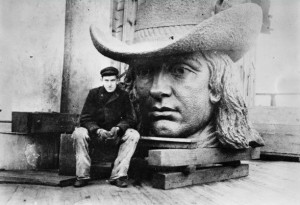

In line with the city’s ambition, no expense was spared in the building’s construction. Most striking was the statue of William Penn placed atop the clock tower. Cast by Alexander Milne Calder (1846-1923), Penn’s likeness was accompanied by 250 additional relief and free-standing Calder sculptures throughout the building, many of them conveying high-minded allegories about the nation and the city.

Patronage

There were other, less commendable reasons for the expense, however. The public buildings commission formed to oversee construction proved a major source of patronage for an increasingly entrenched Republican political machine. A primary force behind the effort was a previously obscure politician, William Stokley (1823-1902), who after his role in the City Hall site selection dominated local politics for nearly than a decade as mayor from 1872 to 1881. In addition to directing contracts for marble and brick to political allies, Stokley’s role in securing a decision to build a single structure at the intersection of the four quadrants that constituted Penn Square at Broad and Market streets solidified relationships with street rail magnates investing in the Union Line. They used the building commission’s decision to force the rival West Philadelphia Company to share its lucrative right away along Market Street in return for permission to lay its tracks around the new structure.

By the time City Hall was complete, its architecture was already considered out of fashion and thus became the object of some ridicule. Objecting to the building’s disruption of traffic as well as its style, city government explored the possibility of demolition in the mid-1950s. When cost estimates came in equal to those for construction and when members of the American Institute of Architects objected to the building’s loss, the city relented. Recent efforts to restore the building have well exceeded the projected cost of its demolition, but the building’s listing on the National Register of Historic Places and its inclusion in a national survey as among the 150 most important buildings in the United States assures its place in Philadelphia for a long time to come.

Howard Gillette is Professor Emeritus of History at Rutgers University-Camden and co-editor of The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2013, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Dilworth Park, City Hall's front entrance reopen to public [photos] (WHYY, September 4, 2014)

- Historically accurate replicas to replace gates to Philly's City Hall courtyard (WHYY, April 13th, 2015)

- Monument Lab: an ideas festival in Philly City Hall's courtyard (WHYY, May 15, 2015)

- Reconstruction begins on north side of Philly's City Hall (WHYY, June 15, 2015)

- Compass restoration is step in the right direction for City Hall courtyard (WHYY, August 4, 2015)

- New multi-use platform coming to Philadelphia City Hall courtyard (WHYY, December 28, 2016)