Constitutional Convention of 1787

Essay

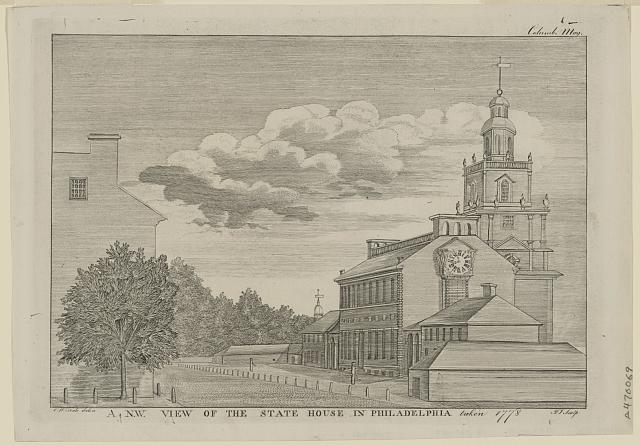

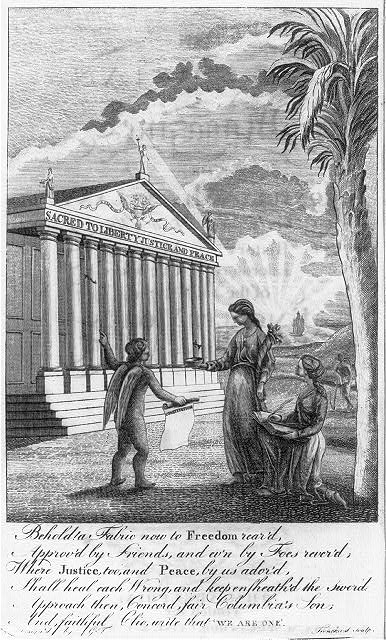

The Constitutional Convention met in Philadelphia from May 25 to September 17, 1787, at Independence Hall (then known as the Pennsylvania State House). The convention drafted the United States Constitution, the world’s oldest written national constitution still in use. The document, which divides power between the federal government and the states, launched a new phase of the American “experiment” in republican government (representative democracy). After being ratified by the American people, the Constitution began operation in 1789 in New York City (the federal capital until 1790) with the convening of the First Congress and the inauguration of George Washington (1732-99) as the first president. The writing of the Constitution in Independence Hall, along with the adoption of the Declaration of Independence there eleven years earlier, has led to global recognition of the building’s historical significance.

By the mid-1780s, several problems had arisen under the Articles of Confederation, which went into effect in 1781. In particular, Congress needed the authority to tax and to regulate commerce. It also needed the means to solve foreign policy problems, such as opening the Mississippi River to American navigation and expelling British troops from several forts in the Northwest Territory. The Confederation Congress called the Constitutional Convention on February 21, 1787, legitimizing a call issued by an earlier convention that met in Annapolis, Maryland, in September 1786 to discuss giving Congress control of commerce. Congress tasked the 1787 convention with revising the Articles to render the federal government “adequate to the exigencies of the union.” All agreed that the convention must strengthen the federal government at the expense of the states. The new constitution needed separate, coequal executive, legislative, and judicial branches restrained by checks and balances so that it could avoid repeating what many regarded as the injustices of the state governments, where, according to conservatives, popular majorities acting through unchecked legislatures often trampled the rights of religious or propertied minorities.

Fifty-five delegates, representing all of the states except Rhode Island, attended the convention in Philadelphia, a geographically central location. The biggest city in the United States, this metropolis of about 40,000 people featured boardinghouses, such as the Indian Queen Tavern and the City Tavern, where the delegates could reside, caucus, and dine. In addition to shops, theaters, and other cosmopolitan amenities, Philadelphia offered a religiously and ethnically diverse and tolerant atmosphere, where men of varying cultures felt comfortable. Many of the delegates found Philadelphia, the former national capital, a familiar place. Southerners, however, considered the antislavery views of the Quakers and like-minded residents troubling. With the windows of Independence Hall’s Assembly Room sealed shut to prevent eavesdropping, the delegates spent the humid summer months deliberating in sweltering conditions.

George Washington, Convention President

The convention, scheduled to open on May 14, did not achieve a quorum until May 25. On the first day, Robert Morris (1734-1806) of Pennsylvania nominated George Washington to be the convention president, to which the delegates unanimously assented. After agreeing to meet from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. six days a week and settling on rules (including keeping the proceedings secret, allowing one vote per state, and requiring at least two delegates to make an official delegation), the convention took up a proposal for the structure of the government. The Virginia Plan, drafted by the Virginians and supported by the Pennsylvanians in the preconvention days, proposed a bicameral legislature with representation in both houses based on either each state’s free population or federal taxes paid, along with executive and judicial branches. John Rutledge (1739-1800) pledged South Carolina’s backing of the Virginia Plan, even though he considered it favorable to the wealthiest and most populous states. In return, James Wilson (1742-98) promised Pennsylvania’s support for counting three-fifths of slaves towards representation in Congress.

The small states, led by William Paterson (1745-1806) of New Jersey, countered with the New Jersey Plan in opposition to the sweeping changes proposed by the Virginia Plan, especially the elimination of the Confederation’s one-vote-per-state system. The New Jersey Plan would essentially add executive and judicial branches to the existing Confederation and grant Congress power over taxation and commerce. At stake were not just the interests of large versus small states, but whether the new framework would be a national government of people, or whether it would continue a confederation of states. Upon reaching an impasse and nearly dissolving, the convention turned the divisive matter over to a grand committee composed of a member from each state. The committee, which included Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) of Pennsylvania, devised the Great Compromise (or the Connecticut Compromise) in which each state’s representation in the House of Representatives would be based on population (including three-fifths the number of slaves), and each state would receive two seats in the Senate. Appropriations bills could only originate in the House. This breakthrough created what James Madison (1751-1836) of Virginia called a partly national, partly federal “compound republic.”

At the end of July the convention recessed for ten days while a five-man Committee of Detail incorporated the agreed-upon resolutions into a draft Constitution. The committee, dominated by Rutledge and Wilson, replaced a blanket grant of power to Congress with a list of enumerated powers. At the same time, however, the draft included blank checks that undermined the concept of enumerated powers, such as the “necessary and proper,” “general welfare,” and “supremacy” clauses. In addition to the three-fifths compromise already agreed upon by the convention, the committee inserted a number of provisions favorable to the South, including a ban on export taxes, and requiring a supermajority of two-thirds of Congress rather than a bare majority to pass commercial legislation. Nor could Congress prohibit the African slave trade.

Struggle Over Slavery Issue

In August, the entire convention struggled with the slavery issue. Several northerners, led by Gouverneur Morris (1752-1816) of Pennsylvania, eloquently attacked the South’s peculiar institution as a moral abomination. The debate led to compromises in which the North traded a fugitive slave provision in return for the South’s abandonment of the supermajority requirement for commercial legislation. The convention prohibited Congress from banning the international slave trade for twenty years, but allowed a ten dollar tax on slave imports. The delegates also decided to use the word “persons” instead of “slaves.” By threatening disunion if slavery were not adequately protected, the South, especially Georgia and South Carolina, got the better of these compromises. The three-fifths compromise in particular secured enough additional seats in Congress to enable the “Slave Power” eventually to enact proslavery legislation such as the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act, which overturned the ban on slavery imposed in those territories by the Missouri Compromise of 1820. Thanks to the Electoral College, moreover, the three-fifths compromise also made it easier to elect southern presidents, who in turn often nominated pro-slavery Supreme Court justices.

The draft constitution called for a president to be elected by Congress for one seven-year term. After considering myriad alternative arrangements, the delegates, at the beginning of September, turned the disposition of the presidency over to the “Committee on Postponed Parts.” Chaired by David Brearly (1745-90) of New Jersey, this committee redesigned the office, giving the executive a four-year term to be elected without a term limit by an electoral college. In accepting this change, the convention created a truly independent executive, coequal with the federal government’s other branches. The convention’s expectation that Washington, the likely first president, would not abuse his power convinced the delegates to take this bold step.

With all of the Constitution’s major provisions decided upon, the convention on September 10 appointed a Committee of Style to prepare the final draft. Gouverneur Morris, an eloquent writer, finalized the preamble and organized the document into its various articles and sections. Not knowing which states would ratify, Morris changed the preamble’s opening from a list of the thirteen states to, “We the People of the United States.”

On September 17, the convention met one last time to sign the embellished manuscript of the Constitution. Benjamin Franklin called on the forty-two delegates still present to add their signatures to the document. George Mason (1725-92) of Virginia, Edmund Randolph (1753-1813) of Virginia, and Elbridge Gerry (1744-1814) of Massachusetts remained unwavering in their opposition. As the delegates one by one affixed their names, Franklin pointed to the half sun carved into the backrest of Washington’s chair. The Pennsylvanian remarked that after wondering all summer whether it was a rising or setting sun, he now knew that it was in fact a rising sun.

The States Decide

The convention forwarded the Constitution to Congress with resolutions specifying that the ratification decision be made by conventions “chosen in each state by the people.” Congress voted unanimously, not to endorse but merely to transmit the document to the states for ratification. Article VII provided that the Constitution would take effect when ratified by nine states. Delaware, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey became the first three states to ratify the Constitution, all by lopsided margins. The Delaware ratification convention, meeting in Dover, happy with the Great Compromise and not wishing to see such a little state become a separate nation, ratified on December 7 by a vote of 30-0. The Pennsylvania convention, held in Independence Hall, approved the Constitution on December 12 by a vote of 46-23, rejecting the Antifederalists’ request to postpone ratification until they had time to propose amendments. The bitter response of Pennsylvania’s unreconciled Antifederalists to the Federalists’ heavy-handed approach caused remaining states to conduct a more thorough and sincere ratification debate. New Jersey’s convention in Trenton, eager for commerce (and import duties) to be controlled by the federal government because of the state’s dependence on out-of-state ports in New York City and Philadelphia, ratified on December 18 by a 38-0 vote. Philadelphians celebrated the Constitution’s ratification on July 4, 1788, with a “Grand Federal Procession” to the Bush Hill estate of William Hamilton (1745-1813), three miles outside of town, where James Wilson delivered a spirited address to a crowd of 17,000. Toasts and a sumptuous feast followed.

Visitors to Independence Hall can see the Assembly Room where the convention met and the Rising Sun Chair where Washington sat. The building, part of Independence National Historical Park, was designated a World Heritage Site by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) for its role in the spread of republican government (representative democracy).

Stuart Leibiger is a Professor and History Department Chair at La Salle University. He is the author of Founding Friendship: George Washington, James Madison, and the Creation of the American Republic (University of Virginia Press, 1999), and editor of a Companion to James Madison and James Monroe (Wiley-Blackwell Publishers, 2013).

Copyright 2015, Rutgers University

Gallery

Backgrounders

Connecting Headlines with History

- Founding Father's desk, papers on display to mark Constitution anniversary (WHYY, September 17, 2012)

- Do we need a new Constitutional Convention? (WHYY, December 23, 2013)

- Supreme Court says same-sex couples have right to marry in all 50 states (WHYY, June 26, 2015)

- Constitution Center focuses on religious freedom's evolution from a concept to a right (WHYY, August 19, 2015)

- From parchment to iPad: U.S. Constitution digitized (WHYY, September 16, 2016)

Links

- Interactive Constitution (National Constitution Center)

- A Teacher's Guide to the Constitutional Convention (TeachingAmericanHistory.org)

- Ratification of the Constitution (TeachingAmericanHistory.org)

- Documents from the Continental Congress and Constitutional Convention (Library of Congress)

- The Constitutional Convention of 1787 (EDSITEMent)