Cordwainers Trial of 1806

Essay

Shoemaking, one of the most lucrative trades in Philadelphia during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, also proved to be one of the most contentious. Dissension within the trade worsened in the last decade of the eighteenth century and climaxed with the Philadelphia Cordwainers (shoemakers) Trial of 1806. This trial proved to be not only a contest between journeymen laborers against master shoemakers but also a trial of Federalist versus Jeffersonian ideals. The ultimate decision upheld Federalist notions of protection of property and firmly placed the United States on a course of enhanced industrial manufacturing through the use of wage labor. As such, it also proved to be one of the most significant trials in American labor history.

Contention between journeymen shoemakers and their masters grew in the last decade of the nineteenth century, as in-migrating master craftsmen began promoting price competition, proposed higher pay rates, and lowered product quality. Both masters and journeymen fought the practice of underselling (marketing cheap goods), as it not only affected profits, but also wages. However, each side did so independently and with its own interests at stake, which foreshadowed the divergence that would take place between them.

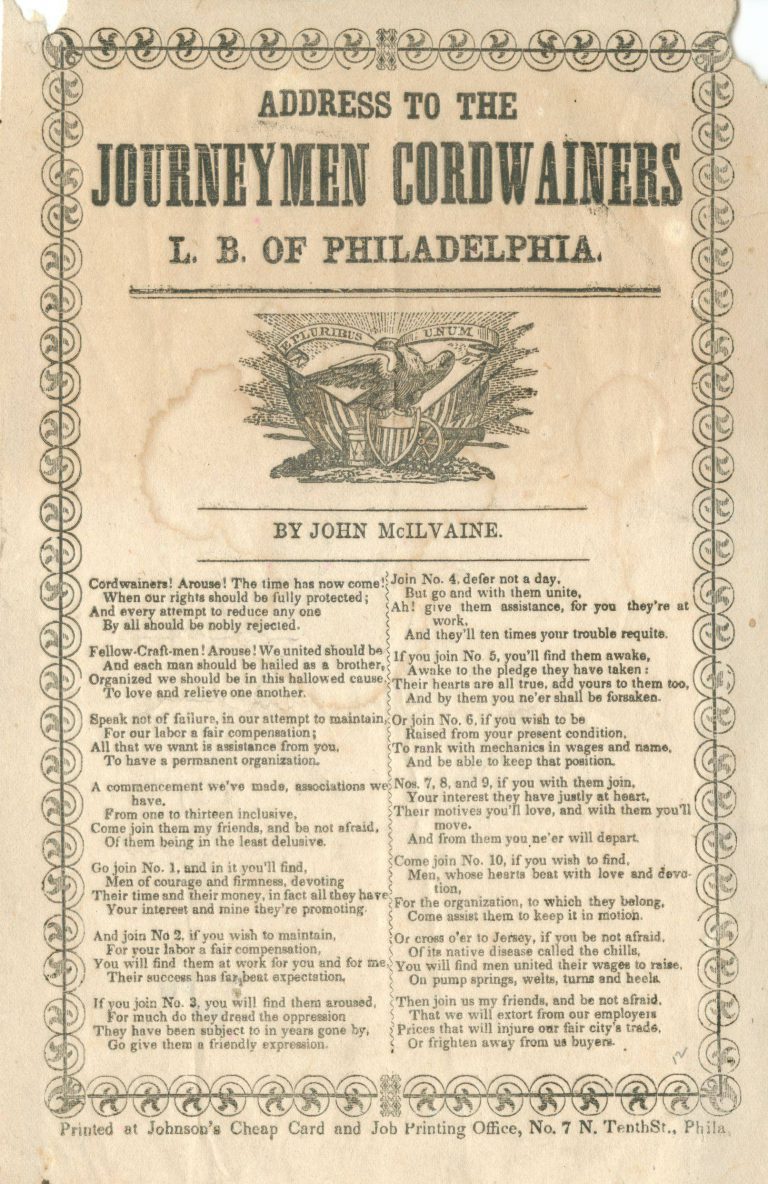

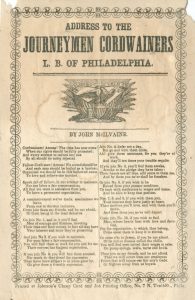

By 1792 journeymen societies grew throughout the city. In 1794 the Federal Society of Journeymen Cordwainers of Philadelphia organized to protect wages, but more significantly to protect journeymen workers from “scab labor,” workers who agreed to work for lower wages. These societies proved effective, as workers received a wage increase in 1798, before a failed 1799 strike led to a general reduction. Soon, masters began to take orders for boots and shoes for the South. However, once orders flowed in, journeymen laid down their tools, demanding a wage increase for “export” products. This strike not only halted production, but ultimately forced masters to default on a number of orders.

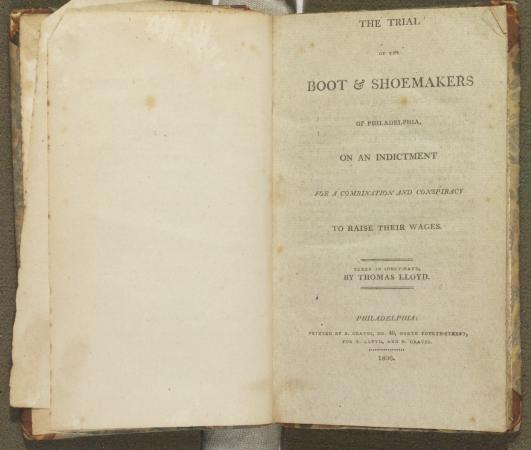

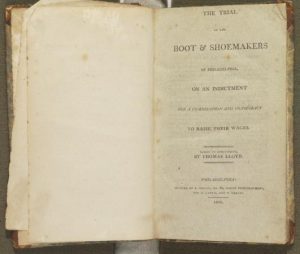

Over the next five years, calm settled over the industry. Journeymen ultimately agreed to a reduction in piece work for export orders, as they initially viewed this as an opportunity for more work and believed the agreement to be temporary. However, by 1805 export work became regular and journeymen demanded not only that the reduced wages for export work be reversed, but also demanded higher rates for customized boots. The masters immediately declined, and in the fall of 1805 journeymen shoemakers initiated a strike that lasted nearly seven weeks. Master shoemakers took the matter to court, and on November 1, 1805, a Philadelphia grand jury indicted eight journeymen on charges of combination and criminal conspiracy to increase wages, bringing the strike to an abrupt end.

The trial, officially known as The Commonwealth v. George Pullis, began March 2, 1806, in the Mayor’s Court and became a political contest between Federalist aristocracy and Jeffersonian democracy. Prosecutors, led by Federalists Jared Ingersoll (1749-1822) and Joseph Hopkinson (1770-1842), argued that journeymen societies not only hampered the shoemaking industry, but threatened the entire economy of the city. They cited English common law forbidding workers’ collusion in order to control the price of labor. They advised the jurors that allowing these societies to exist would set an example for other trades that might foment hostilities, violence, and potential civil war. The prosecution retorted that these societies were a menace to social stability and the public welfare.

The defense, led by Democratic-Republicans Caesar Augustus Rodney (1772-1824) and Walter Franklin (1773-1836), argued that workers had the right to organize and receive wages comparable to those of journeymen shoemakers in Baltimore and New York City. They contested the prosecution’s use of English common law, claiming that it no longer applied to Pennsylvania. Furthermore, they argued that no law existed in Pennsylvania that prohibited journeymen from organizing for wage increases. Using rhetoric drawn from the American Revolution, Rodney and Franklin asserted that the masters’ control over their laborers as a form of wage slavery comparable to the tyranny colonists had fought against.

After both sides presented their case, Federalist Judge Moses Levy (1757-1826) used his charge to the jury to extol the ideals of a laissez-faire market and its ability to determine both prices and wages. He denounced the existence of journeymen societies, their use of strikes, and the artificial regulation this put on the market. Lastly, he instructed the jury to understand that a combination of workers, formed into a society in order to raise their wages, was illegal under common law. The next day the jury found the eight journeymen guilty and fined them eight dollars each.

The Philadelphia Cordwainers Trial, or Conspiracy Trial, of 1806 as it was popularly known, had far-reaching implications for antebellum society and labor. It upheld the Federalist ideals of protecting property and legitimizing growth of American industry unrestrained by workers’ organizations. As for labor, the trial ultimately made any workers’ societies, or trade unions designed to control prices or wages, illegal in America. This decision held until the 1842 Massachusetts Supreme Court trial of Commonwealth vs. Hunt permitted labor unions to operate lawfully. The Pullis decision was the first of many court rulings against labor in Philadelphia in the first two decades of the nineteenth-century, a fact not lost on labor leaders of the city. Unfavorable courts became one of the primary reasons labor turned towards politics to solve their problems during the Jacksonian Era.

Patrick Grubbs is a Ph.D. candidate at Lehigh University who is writing his dissertation, titled “The Duty of the State: Policing the State of Pennsylvania from the Coal and Iron Police to the Establishment of the Pennsylvania State Police Force, 1866–1905.” He has been employed at Northampton Community College in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, since 2009 and has taught Pennsylvania history there since 2011. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2016, Rutgers University