Crowds (Colonial and Revolution Eras)

By Toni Pitock

Essay

Social and economic elites dominated formal politics in Pennsylvania and New Jersey during the colonial and revolutionary eras, but ordinary people, often those who were ineligible to vote, helped shape the political culture. To support or oppose economic conditions and policies imposed by imperial, provincial, and local legislators, they periodically engaged in public celebrations, civil disorder, and, occasionally, collective violence.

Unrest arose during periods of unemployment and economic stress. In Pennsylvania in the 1720s, hundreds of urban and rural commoners protested when Governor William Keith (1669-1749) refused to sign the Assembly’s paper currency bill, meant to pull the colony out of a steep recession. They assailed merchants and political authorities, and threatened to raze the house of James Logan (1674-1751), former mayor and ally of the Penn family. In response, the assembly issued £30,000 in bills of credit.

Economic difficulties brought another conflict during the 1742 election as the dominant Quaker party and the opposition Proprietary party vied for control of the Assembly, and nonvoting supporters clashed as they coerced and harassed voters. German settlers supported the Quakers. They shared pacifist principles and relied on favorable loans, easy ground rents, and land grants from the Quakers. On October 1, 1742, a crowd of eighty armed seamen and waterfront workers arrived at the polls to express their opposition to the Quakers, who restricted privateering during the War of Jenkins’ Ear (1739-48), a conflict between Britain and Spain as Britain tried to expand trade in the Caribbean. This constraint shut off an additional avenue for employment at a time when the war reduced opportunities for work. The sailors rushed the courthouse. They threatened to level the building, shouted abuses at the Quakers, and attacked their German supporters who responded with violence. A similar episode occurred in the 1752 elections in York County when Irish and Germans factions clashed.

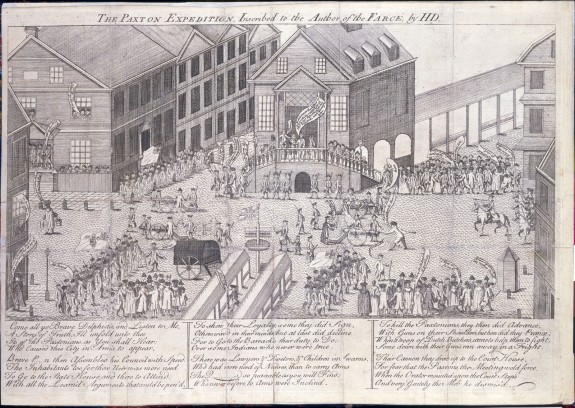

Inhabitants of the region made their voices heard when they believed that the actions of authorities worked against their interests. In 1756, Philadelphia tradesmen rioted when the British army began enlisting runaway servants, invalidating the terms of indentures. While frontier settlers generally sought to escape the reach of government, they expected protection from marauding Indians. In November 1755, a Lancaster Pike tavern keeper led two hundred angry western settlers to Philadelphia where they threatened the pacifist Assembly with violence. In February 1764, in the wake of Pontiac’s War and two massacres during which settlers attacked peaceful Indians in Conestoga Town, 250 “Paxton Boys” headed toward Philadelphia. A crowd of three thousand Philadelphians gathered in front of the State House and demanded that the Assembly protect them against the marchers. Governor John Penn (1729-95) urged them to defend the city while Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) met the marchers at Germantown to hear their grievances and averted a confrontation.

Imperial Crisis

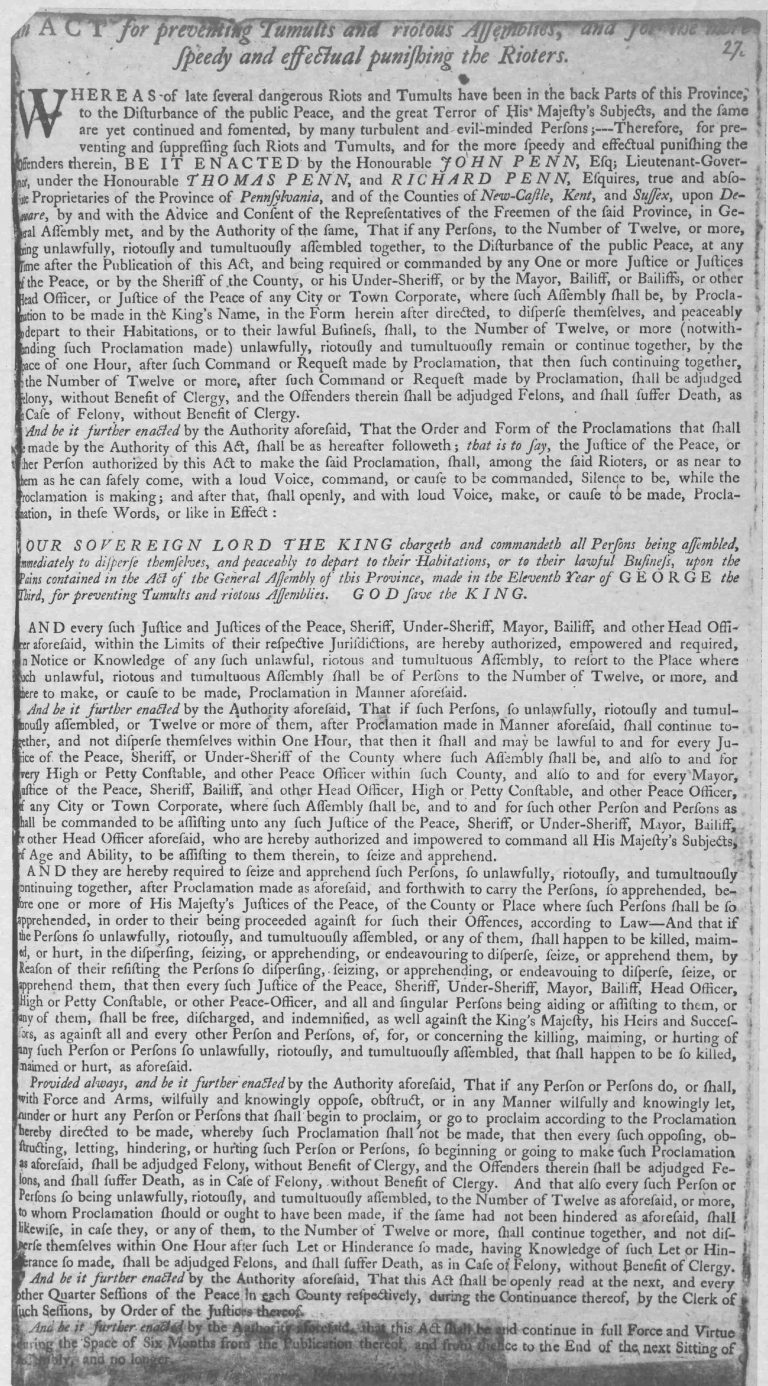

Following the Seven Years’ War, the Pennsylvania legislature debated the taxes and duties imposed by Britain behind closed doors. Not to be excluded from articulating their views, the public created a vibrant informal political culture “out of doors.” Ordinary people defended their “liberty” in newspaper articles and pamphlets and responded to each new Act of Parliament as well as the Assembly’s responses. Crowds aired grievances at mass meetings and protests that sometimes culminated in vandalism and violence. Crowd actions in New Jersey tended to be in the northern part of the colony.

News of the Stamp Act on September 16, 1765, drew a crowd to the Court House at Second and Market Streets, and remonstrators threatened to attack the homes of Crown supporters, most notably Benjamin Franklin (1706-90) and Joseph Galloway (1731-1803), both members of the Assembly, and John Hughes (1711-72), the official appointed to oversee compliance. A more moderate group of eight hundred men who formed an association “for the Preservation of Peace” persuaded protesters to disperse on that occasion. The arrival of the official stamps on October 5 renewed opponents’ indignation. Several thousand inhabitants of Philadelphia gathered to demand Hughes’s resignation. A month later, a crowd hanged Hughes in effigy while Quaker party supporters raised their voices in support of Hughes and Parliament.

Opposition mounted with the Townshend Revenue Act (1767) and the Tea Act (1773). Radical leaders, among them John Dickinson (1732-1808) and the merchant Charles Thomson (1729-1824), attempted to organize nonimportation agreements while artisans and mechanics pressured hesitant members of the community, especially merchants, to participate in boycotts. In an effort to enforce compliance, they assembled on wharves to prevent merchants from unloading ships carrying British imports. Sailors, who opposed boycotts and embargoes, acted against supporters of nonimportation. In October 1769, a mob of seamen tarred and feathered a man who informed about illegally imported goods. In December 1773, eight thousand people gathered outside the State House to voice their opposition to the Tea Act.

The actions of the first Continental Congress (1774) and the Articles of Association, which boycotted trade with Britain and prohibited consumption of British goods, further mobilized the public. Committees of Safety seeking to enforce nonimportation stirred supporters to act against merchants who raised prices or hoarded goods and against elites who flouted regulations. In 1775, locals threatened to raze the City Tavern, where a ball honoring Martha Washington (1731-1802) was planned. The ball contravened Congress’s proscription on entertainment, and the City Tavern, a gathering place for Philadelphia’s leading citizens, was a symbol of their immoderation. The threat of violence prompted Congress to cancel the affair.

Revolutionary Crowds

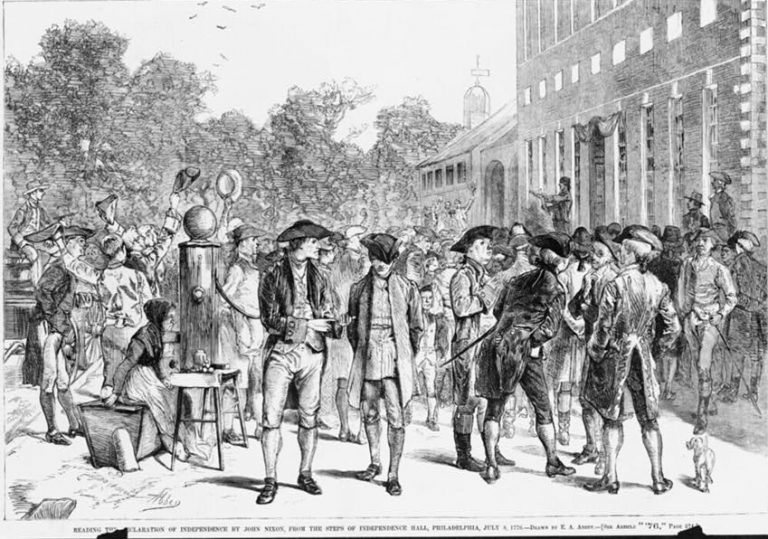

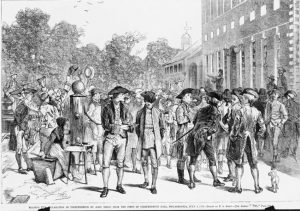

Once the colonies declared independence, crowds expressed their views through festivities and street theater as well as protests. Cheering crowds gathered in the State House yard to hear the Declaration of Independence and celebrated with bonfires and bell-ringing. In New Castle, Delaware, the Declaration of Independence was read publically on July 24 to a cheering crowd that promptly burned the King’s Arms that had formerly hung in the courthouse. In June 1778, following the British evacuation of Philadelphia, dissatisfaction with the mood of the official Fourth of July parade led the “people out of doors” to coordinate a second procession. The boisterous crowd parodied the loyalist women who delighted in the entertainments of the British during the occupation. They paraded an extravagantly dressed and coifed “Negro Wench,” whom they called “Continella.” Two years later, news of the treason of Benedict Arnold (1741-1801) in September 1780 brought crowds into the streets on two consecutive days. They showed their loathing for the profligate former military governor and traitor by hanging and burning effigies of Arnold and, at the same time, cautioned others against collaborating with the British.

Middling and lower sorts suffered hardships during the Revolution and resented the patriot elites who manipulated food prices and avoided military service. Sailors rioted in January 1779, demanding higher pay. In May, at a public meeting organized to appoint committees to investigate rising prices, leaders tacitly approved crowd action when they resolved that the public had a right to prevent abuses through price controls or some other means. Following the meeting, thousands were reported to have rioted, and crowds escorted a merchant, a butcher, and a speculator to the city jail. On October 4, two hundred militia members planned to make examples of the worst culprits by parading them through the streets. Their march culminated in a clash with the merchant elites at the home of James Wilson (1743-98), an event known as the Fort Wilson incident. In June 1783, a crowd of army veterans gathered outside the State House to demand back pay, forcing the Continental Congress to flee to Princeton, New Jersey.

Colonial and revolutionary crowds acted of their own accord, protesting legislative measures and punishing enemies of the common good. Their legacy was preserved in Pennsylvania’s 1776 Constitution and in subsequent versions, which protected the right of the people to assemble, to express their grievances, and to demand redress.

Toni Pitock received her Ph.D. in History from the University of Delaware. Her manuscript in process explores the economic culture of Philadelphia’s Jewish commercial community from its emergence in 1736 until the early 1820s. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2017, Rutgers University

Gallery

Links

- The American Revolution, 1765-1783 (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Occupation of Philadelphia (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- James Wilson Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- Desperation, Zeal, and Murder: The Paxton Boys (Penn State University)

- Quaker Protest Against Slavery in the New World, Germantown (Pa.) 1688 (Haverford College)

- "Common Sense" Historical Marker (ExplorePAHistory.com)

- The President's House Site (National Park Service)