March of the Mill Children

Essay

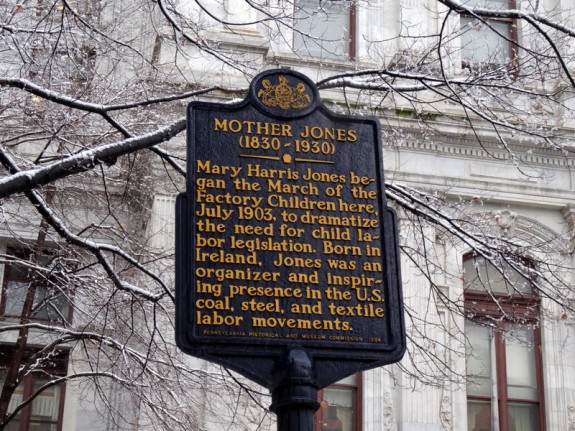

The March of the Mill Children, the three-week trek from Philadelphia to New York by striking child and adult textile workers launched on July 7, 1903, by Mary Harris “Mother” Jones (1837-1930), trained public attention on the scourge of child labor and energized efforts to end it by law.

Jones, the storied Irish-born labor organizer, came to the Kensington section of northern Philadelphia in mid-June 1903 to rally support for some 46,000 textile workers, including many youths, who were staging the largest strike in city history to demand a reduced work week of 55 hours and a ban on night work by women and children. Told that newspapers were ignoring child labor because mill owners were stockholders, she retorted, “I’ve got stock in these little children, and I’ll arrange a little publicity.”

A fierce opponent of child labor and a masterly tactician, Jones seized on a march of young workers as a way of publicizing the strike while also exposing the evils of child labor and the excesses of industrial capitalism. Children were sent to work in coal mines and mills to supplement meager family incomes and as a result suffered stunted growth and maiming injuries. The 1900 census reported that one-sixth of American children under age 16 were employed, likely a gross undercount. More children worked in textile manufacturing than in any other trade. By 1900, textile factories and allied trades dominated Kensington, an early manufacturing center.

Philadelphia to New York

At a rally in Kensington’s Labor Lyceum Hall (2914 N. Second Street), Jones revealed plans to lead an “industrial army” of hundreds of child strikers and their parents on a march of nearly 100 miles to New York City to dramatize their cause. She later expanded the itinerary to include a pilgrimage to President Theodore Roosevelt’s Long Island summer home to plead for child labor laws.

The marchers left Kensington to the sound of fifes and drums, heading to Bristol and Morrisville in Pennsylvania. From there, dwindling in numbers, fed and sheltered by unionists, farmers, socialists, and other allies, the ragtag crusaders slogged through heat and rain into the manufacturing belt of New Jersey, soliciting donations and staging rallies often attended by thousands. Their route extended from Trenton, Princeton, and New Brunswick north to Elizabeth, Newark, and Paterson, then into Passaic and Jersey City.

Torchlight parade

Reaching New York City on July 23, sixty marchers paraded up Second Avenue by torchlight. On Coney Island three days later, Jones put children in animal cages to dramatize what she labeled bosses’ attitudes toward workers. She and a delegation of five arrived July 29 at Roosevelt’s Sagamore Hill summer home, where they were rebuffed by his secretary. In the meantime, even before the crusade’s end, strikers thwarted by the manufacturers’ strategies and their own factional divisions had begun returning to the mills.

Nevertheless, the march advanced efforts to abolish child labor. In 1904, the National Child Labor Committee formed for advocacy and action. A year later Pennsylvania toughened its child labor laws, though it took another thirty-three years, until the New Deal presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt, for nationwide legislation protecting young workers, the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, to replace a patchwork of state laws.

Gail Friedman holds a Master’s Degree in Public History from Temple University. She worked as a community planner for Bucks County, Pennsylvania, from 1999 to 2015. (Author information current at time of publication.)

Copyright 2014, Rutgers University.

Gallery

Links

- Philadelphian Mill Children March Against Child Labor Exploitation (Global Nonviolent Action Database, Swarthmore College)

- Actress Betsy Means Portraying Mother Jones (YouTube)

- Mother Jones Museum

- Philadelphia Workshop of the World: Kensington (Oliver Evans Chapter, Society for Industrial Archaeology)